Biological Weapons Convention: Challenges, Limitations, Opportunities, and Approaches

Low-probability, high-consequence (LPHC) biological risk mitigation, applications for Artificial Intelligence technology

The evaluation and opinions expressed below are those of the author, and do not represent positions or viewpoints of the United States Government, the US State Department, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

There is growing interest in updating the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), and there is a real but constrained opportunity to do so, shaped by both political momentum and structural limits.

On the interest side, many states, experts, and international organizations increasingly recognize that rapid advances in biotechnology, lessons from COVID-19, and rising concern about accidental and dual-use risks have outpaced the BWC’s Cold War–era design. This has led to renewed discussion in Review Conferences and intersessional processes about strengthening implementation, transparency, scientific advice, preparedness, and risk governance, often framed around closing “gaps” rather than rewriting the treaty.

The opportunity, however, is politically narrow. Deep reforms such as binding verification remain contentious due to sovereignty concerns, mistrust among major powers, and fears of exposing sensitive research. As a result, the most viable path forward lies in incremental updates: expanding norms and expectations through interpretive understandings, confidence-building measures, scientific advisory mechanisms, capacity building, and new voluntary or soft-law arrangements. In short, there is an appetite to modernize how the BWC functions, but meaningful progress is most likely to come through pragmatic, step-by-step strengthening rather than sweeping treaty revision.

Low-probability, high-consequence (LPHC) biological risk mitigation

Low-probability, high-consequence (LPHC) biological risks pose a distinctive risk management challenge because their rarity belies the scale of devastation they could inflict on global health, security, and stability. The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) can be updated to address LPHC biological risks by expanding its focus from prohibition alone to proactive, collective risk management. Key opportunities and avenues include:

1. Broaden the Treaty’s Scope Beyond Intentional Misuse

The BWC could explicitly recognize catastrophic biological harm arising from accidents, institutional failures, or dual-use research, not only hostile intent. This would align the treaty with modern risk realities, where the most severe outcomes may occur without malicious actors.

2. Establish International Biosafety and Biosecurity Standards

Binding or harmonized global standards for high-risk laboratories, pathogen handling, and research practices could be developed under the BWC umbrella, including requirements for risk–benefit assessment of research with plausible catastrophic downside risks.

3. Introduce Transparency, Reporting, and Verification Mechanisms

Updating the BWC to include mandatory reporting on high-containment facilities, high-risk research activities, and biosafety incidents—paired with peer review, inspections, or auditing mechanisms—would reduce blind spots where LPHC risks can silently accumulate.

4. Create a Standing Risk Assessment and Horizon-Scanning Body

A permanent scientific and technical body could be tasked with monitoring emerging biotechnologies, identifying LPHC risk pathways, and issuing guidance or early warnings, helping the treaty shift from reactive to anticipatory governance.

5. Integrate Worst-Case Scenario Preparedness Obligations

The BWC could complement the International Health Regulations by requiring states to plan, stress-test, and coordinate for extreme biological events, including cross-border response mechanisms for system-overwhelming outbreaks.

6. Address Self-Propagating and Transboundary Technologies

New protocols or interpretive agreements could clarify governance for technologies such as gene drives and other self-spreading biological systems, which would require international consultation, risk assessment, and consent before environmental release.

7. Strengthen Institutional Capacity and Compliance Support

Enhancing the BWC’s institutional infrastructure—funding, technical assistance, and capacity-building—would help reduce global disparities in biosafety and ensure that risk governance expectations are realistically achievable across states.

Updating the BWC to address LPHC biological risks does not require abandoning its core prohibition on biological weapons; rather, it should be extended into a comprehensive framework for prevention, transparency, and catastrophic risk governance. By focusing on outcomes and systemic risks rather than intent alone, the BWC could remain fit for purpose in an era of rapidly advancing biotechnology and global interdependence.

Applying artificial intelligence technology to strengthen the Biological Weapons Convention

Artificial intelligence (AI) could strengthen the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) by enhancing transparency, early warning, and risk governance without altering the treaty’s core prohibition. Applied carefully, AI can help compensate for the BWC’s long-standing weaknesses in verification, monitoring, and anticipatory risk management.

1. Early Warning and Anomaly Detection

AI systems could analyze global health data, laboratory incident reports, trade flows, and open-source scientific publications to detect anomalous patterns that may indicate emerging biological risks, unsafe research trajectories, or potential treaty circumvention. This would support earlier intervention long before a crisis or violation becomes visible.

2. Monitoring Scientific and Technological Developments

Machine learning tools can continuously scan and categorize vast volumes of life-sciences research to identify trends associated with dual-use potential or catastrophic risk pathways. A BWC-linked technical body could use these insights for horizon scanning, helping states keep pace with rapidly evolving biotechnology.

3. Strengthening Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures

AI could assist in analyzing states’ confidence-building measure (CBM) submissions for inconsistencies, omissions, or unusual changes over time. Automated cross-checking against open data sources would improve the credibility and usefulness of CBMs without requiring intrusive inspections.

4. Risk Assessment and Scenario Modeling

AI-enabled modeling could support shared international assessments of low-probability, high-consequence biological risks by simulating worst-case outbreak scenarios, cascading system failures, and cross-border impacts. This would help shift the BWC from intent-based compliance toward outcome-focused risk governance.

5. Supporting Verification and Compliance (Indirectly)

While AI cannot replace inspections, it can support “verification by analysis” through satellite imagery interpretation, supply-chain monitoring, and pattern recognition across multiple data streams. This could lower the political and technical barriers to introducing stronger compliance mechanisms under the BWC.

6. Capacity Building and Global Equity

AI tools could help standardize biosafety practices, provide decision support for risk–benefit analysis in research oversight, and offer early-warning capabilities to countries with limited technical resources. This would reduce global disparities that currently create biosecurity blind spots.

7. Enhancing Crisis Coordination and Response

During suspected biological incidents, AI could support rapid information synthesis, attribution analysis, and coordination among states and international organizations, reinforcing trust and reducing misinformation during high-stakes events.

AI can help transform the BWC from a largely normative prohibition into a more operational, anticipatory, and data-informed governance regime. If deployed transparently and multilaterally, AI would not replace political commitment or legal authority, but it could significantly strengthen the Convention’s ability to detect, assess, and manage low-probability, high-consequence biological risks in a fast-moving technological landscape.

Conclusion

While the Biological Weapons Convention remains a cornerstone of international biosecurity, it is increasingly misaligned with contemporary biological risk realities. Advances in biotechnology, lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, advocacy for field applications of gene drive technology, and growing concern over accidental, dual-use, and systemic risks have generated renewed interest in updating the BWC. However, political constraints, particularly around sovereignty, trust, and verification, limit the feasibility of sweeping treaty reform. As a result, the most realistic path forward lies in incremental yet meaningful strengthening through expanded norms, improved transparency, enhanced scientific advisory capacity, strengthened preparedness obligations, and institutional support, rather than a wholesale revision of the treaty.

Addressing low-probability, high-consequence biological risks requires the BWC to evolve from a framework focused primarily on prohibiting deliberate misuse into one capable of managing catastrophic outcomes regardless of intent. By broadening its scope to include accidental and dual-use risks, establishing international biosafety standards, improving reporting and oversight, and creating mechanisms for horizon scanning and worst-case preparedness, the Convention could better reflect the systemic and transboundary nature of modern biological threats. The integration of artificial intelligence further offers a practical opportunity to enhance early warning, risk assessment, transparency, and capacity building without undermining the treaty’s core prohibitions. Together, these steps point toward a pragmatic vision of modernization: one that preserves the BWC’s foundational norm against biological weapons while transforming it into a more anticipatory, data-informed, and resilient system for managing catastrophic biological risk in an era of rapid technological change.

References

Arms Control Association. (2022). The Biological Weapons Convention at a glance. Arms Control Association.

Bostrom, N. (2013). Existential risk prevention as global priority. Global Policy, 4(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12002

Burkle, F. M. (2021). Declining public health protections within the Biological Weapons Convention: Lessons from COVID-19. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 15(3), 300–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.431

Convention on Biological Diversity. (2000). Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety. United Nations.

Enemark, C. (2017). Biosecurity dilemmas: Dreaded diseases, ethical responses, and the health of nations. Georgetown University Press.

Findlay, T. (2006). Verification of the Biological Weapons Convention. United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR).

Global Preparedness Monitoring Board. (2019). A world at risk: Annual report on global preparedness for health emergencies. World Health Organization.

Koblentz, G. D. (2020). Emerging technologies and the future of the Biological Weapons Convention. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76(4), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1778364

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Biodefense in the age of synthetic biology. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24890

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Reducing the risk of biological accidents. OECD Publishing.

Relman, D. A., Choffnes, E. R., & Mack, A. (Eds.). (2010). The domestic and international impacts of the 2001 anthrax attacks. National Academies Press.

Revill, J., & Jefferson, C. (2014). Confidence-building measures and the Biological Weapons Convention. Nonproliferation Review, 21(3–4), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2015.1070062

Scharre, P. (2018). Army of none: Autonomous weapons and the future of war. W. W. Norton & Company.

(Supports AI-enabled monitoring and verification concepts.)

Tucker, J. B. (2011). Innovation, dual use, and security: Managing the risks of emerging biological and chemical technologies. MIT Press.

United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. (2022). Ninth Review Conference of the Biological Weapons Convention: Final document. United Nations.

World Health Organization. (2005). International Health Regulations (2005). WHO.

World Health Organization. (2021). Global laboratory biosafety guidance. WHO.

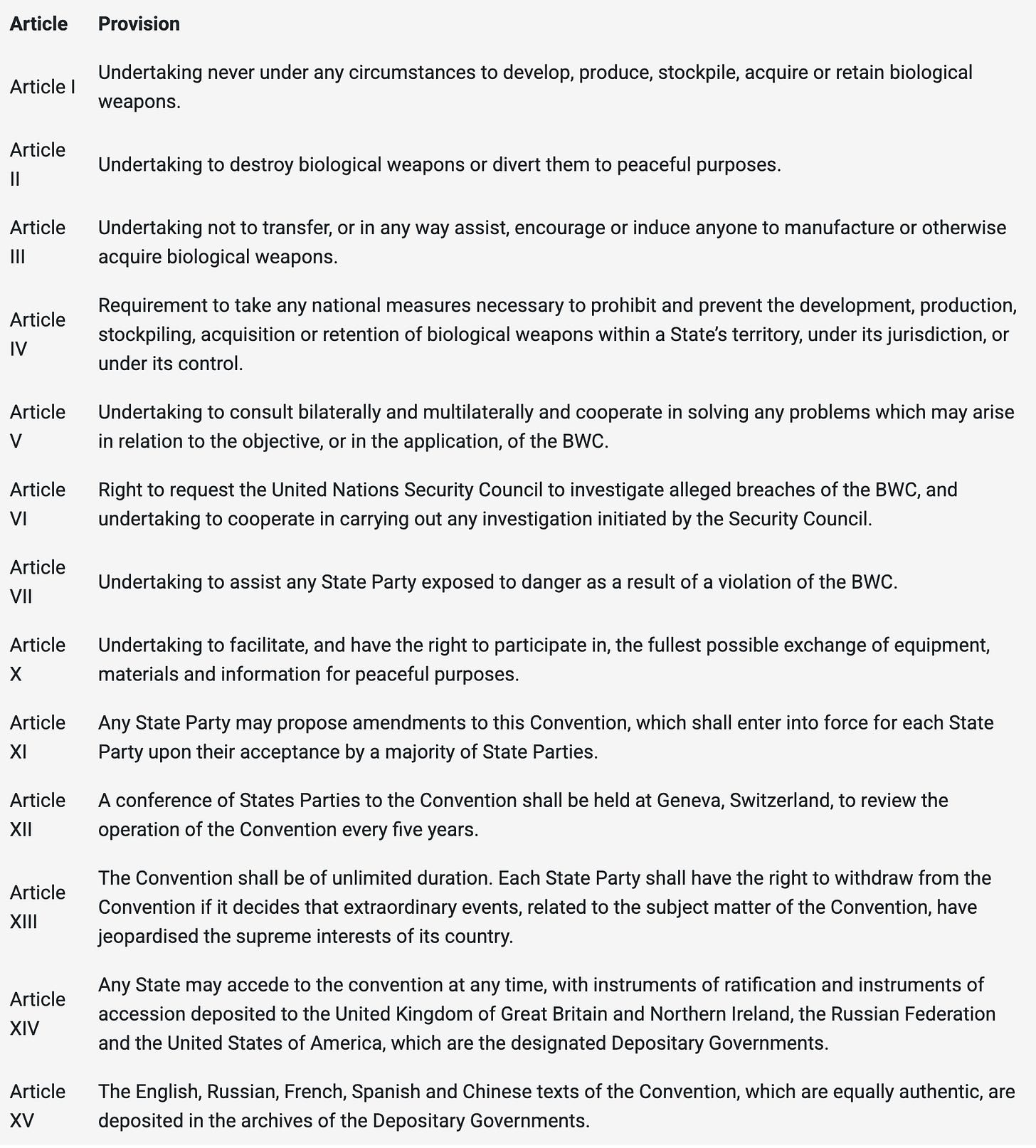

Summary of the Biological Weapons Convention

The BWC itself is comparatively short, comprising only 15 articles. Over the years, it has been supplemented by a series of additional understandings reached at subsequent Review Conferences. The BWC Implementation Support Unit regularly updates a document that provides information on additional agreements which (a) interpret, define or elaborate the meaning or scope of a provision of the Convention; or (b) provide instructions, guidelines, or recommendations on how a provision should be implemented.

The text of the Convention is available for download in the six official UN languages: English, Spanish, French, Russian, Chinese, Arabic.

Formally known as “The Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction”, the Convention was negotiated by the Conference of the Committee on Disarmament in Geneva, Switzerland. It opened for signature on 10 April 1972 and entered into force on 26 March 1975. The BWC supplements the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which had prohibited only the use of biological weapons.

My question on this subject is once dangerous/threatening activity is detected...then what? Financial warfare? Physical interdiction? Sticky wicket what. I think knowledge of the potential of biothreats should prompt a strong surge into research on prevention/mitigation of the effects of such agents as transparency is an unreliable defense.

Again, you have well set out the needs for an enhanced vigilance for biological threats.

As pointed out, we have discovered University studies (gof Wisc Mass) being conducted on their own volition. We have had Chinese students bringing in fungi (trial balloons?). We have had experiences where China has not been above board. According to Mike Benz and the Promethean folks point out the people involved and characteristics of the Minnesota uprising are consistent with CIA color revolutions. There are research operations located in countries outside of the country of origin.

That is to say there are identifiable threats as well as the unintended risks. There is clear justification for enhanced vigilance. In view of the many weaknesses of nations involved with the existing agreement, focused incremental enhancements are the only viable approach.

I'm not a techie. Recognizing it could offer valuable support, I'll leave the AI call to the prepared.

Hopefully your publications will reach involved sources and spur concern and action!