Life on Earth

Watch, Listen, and Think

In my possession is the last physical legacy of my now long-passed parents - that is, the many trinkets, family letters, junk, journals, papers, photos, and books that reside throughout our home, left to me with the death of my father in 2018.

They tell the story of my ancestors. Their loves, lives, prosperity, and hardship. These physical artifacts offer glimpses into the inner workings of the people who came before me. Notably, my father’s family resided in both northern Florida and Southern Alabama, particularly around the Dothan area.

The Malones were a prominent family, and stories abound of their many exploits. My great-great-great-grandfather (George Y. Malone) went to California and co-founded the Stanislaus gold mine in California’s Calaveras County (known for “melones” gold), but he was bought out by Stanislaus when his father died, and he needed to return home to care for his family quickly. Stanislaus had a California river and a county named after him. George Y Malone returned home a relatively wealthy man. He then fought in the Civil War directly under General Stonewall Jackson (Alabama Second Infantry), where he was severely injured in the Battle of Richmond, saved by his servant, and had a leg amputated. Returning to Alabama with the rank of Captain in the CSA, he then established the Bank of Dothan, which, over a hundred years later, became SouthTrust Corporation and later merged with Wachovia Bank. This propelled Wachovia to become the fourth-largest bank holding company in the United States, with almost half a trillion in assets at its peak, making many in my extended family quite wealthy in the process. Eventually, it all collapsed in the great recession of 2008, and Wachovia merged with Wells Fargo, marking the end of most of my family’s role in the banking industry, although a local bank remains active.

My grandfather, who was president of the Bank of Dothan, died early (in the 1930s), of heart failure consequent to rheumatic fever. Control of the bank then passed to a different branch of the Malone family. My dad’s grandfather, also a banker, had brought all of his children into the banking industry. Influenced by his time spent with his grandfather around Pensacola, my own father left the South as a young man to join the Navy (Naval Signal Intelligence stationed in Japan), then attended Stanford University, became an electrical engineer on the West Coast, and never entered the banking business that had defined our family for generations.

My great-grandfather, affectionally known as “Dar” (Edgar Robert), was known for his love of nature, and upon retirement, he lived a solitary and simple life in the backwoods of Alabama and on the shores of Florida—by choice. His outsized presence in my father’s early life (after his own father had passed away) was why my father loved the sea. Dar was also known for his philanthropic work, and had many prominent and like-minded people as friends.

Of note, Dar and his brothers founded the Florida town of Malone. Their legacy left me and a few relatives 3500 acres of mineral and gas rights in Northern Florida, which doesn’t seem to have much value by all appearances.

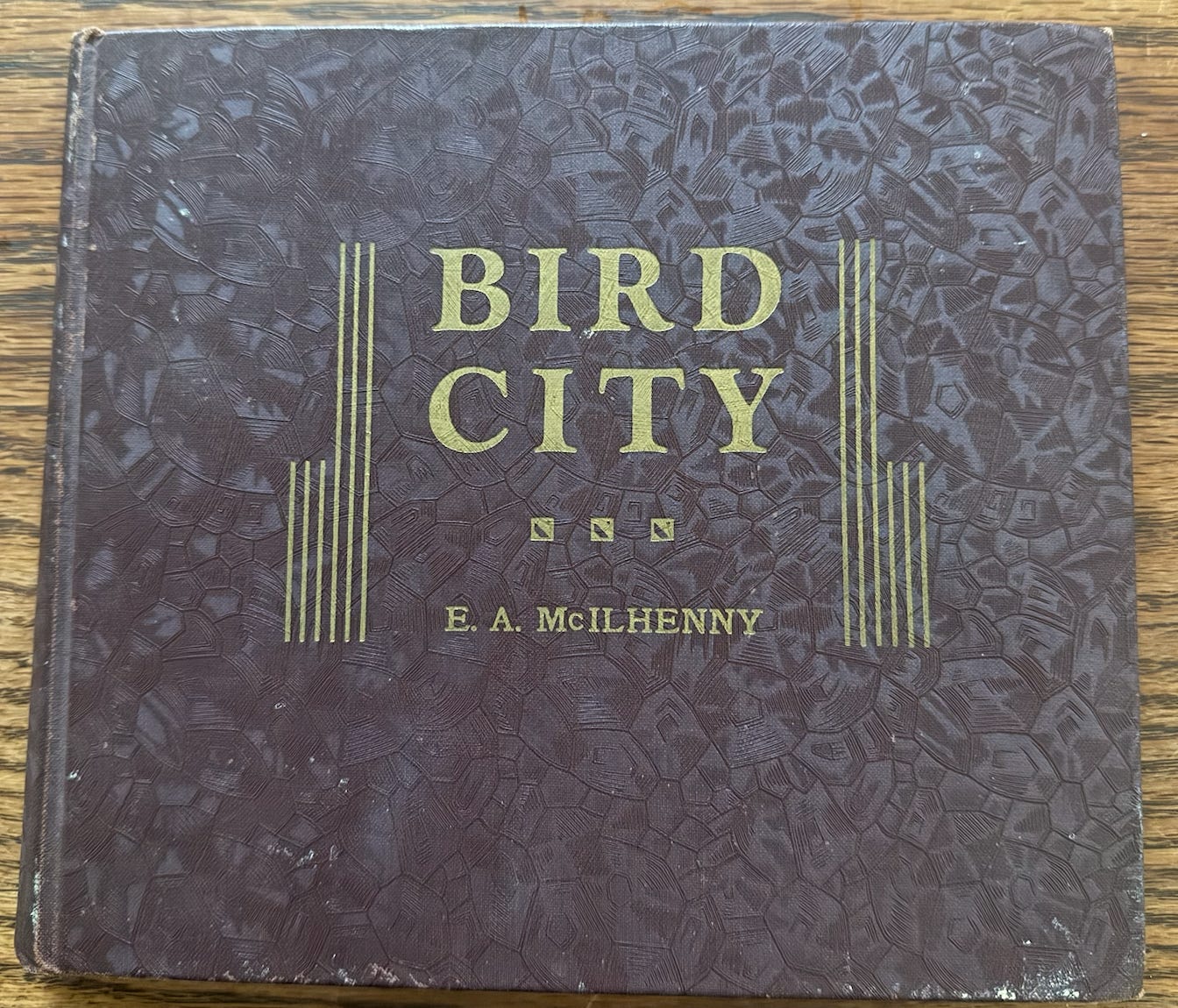

Anyway, some of Dar’s library was passed down to my father and then to me, and there are many books that various authors personally signed. In that collection is a slim volume by E. A. McIhenny called “Bird City.” This book was written in 1934 by the man whose father invented Tabasco sauce, which he then expanded into a worldwide phenomenon, making a fortune in the process.

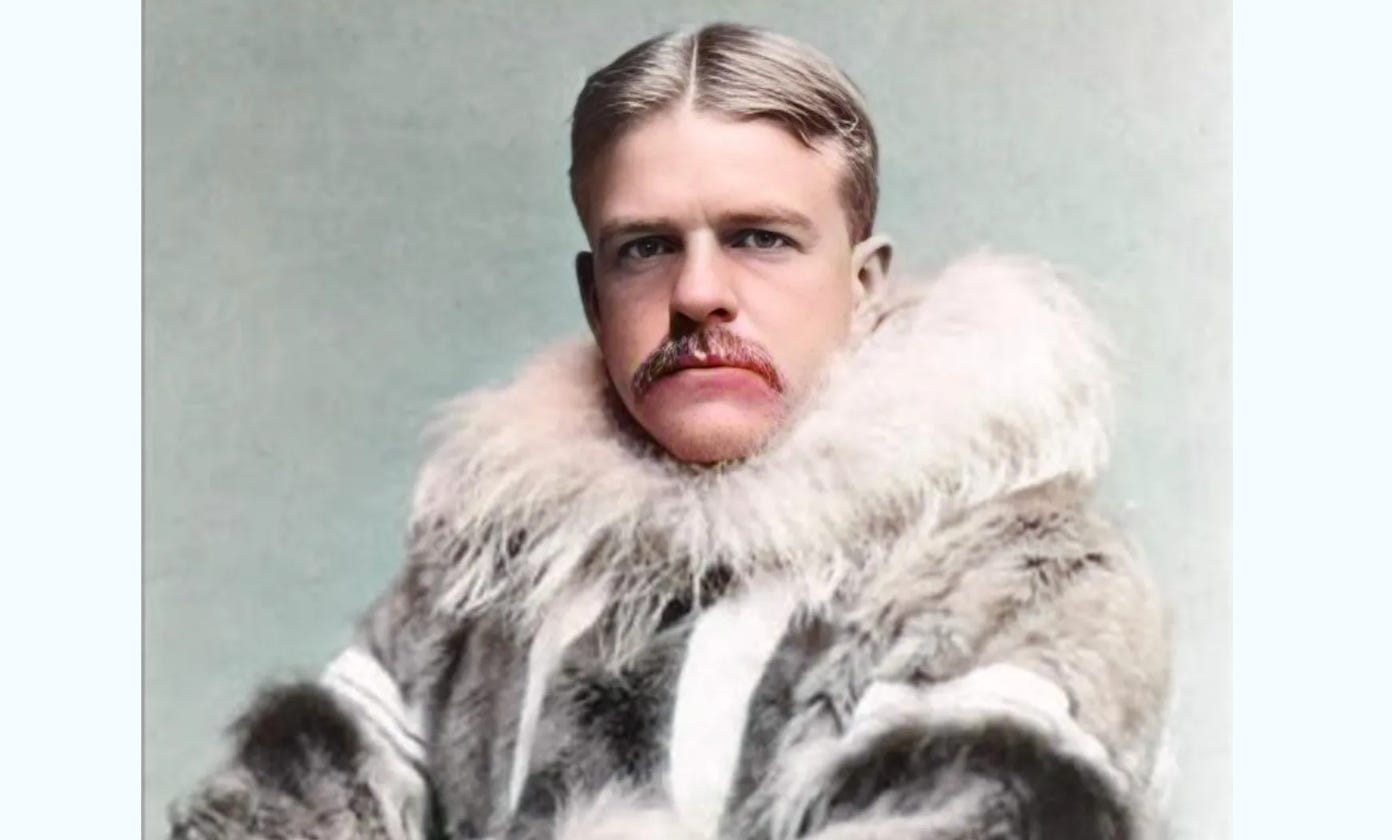

Edward Avery McIlhenny, often known as "Ned," was also a naturalist, explorer, and conservationist, most often remembered for his pioneering work in wildlife preservation and botany.

He founded the Bird City wildfowl refuge on Avery Island, Louisiana, around 1895, successfully helping to save the snowy egret and other wading birds from extinction. During his life, he was instrumental in securing nearly 175,000 acres of Louisiana coastal marshland as wildfowl refuges. He personally banded almost 200,000 birds and had a hands-on role in managing this vast conservation project.

McIlhenny was also an Arctic explorer, participating in Frederick Cook’s 1894 Arctic expedition as an ornithologist. He later led his own expedition to Point Barrow, Alaska, in 1897 and was also involved in explorations on the African continent in search of new species. He collected hundreds of animal and ethnological specimens, many of which are still housed in major museums. In his era, he was known as one of the great naturalists of his generation.

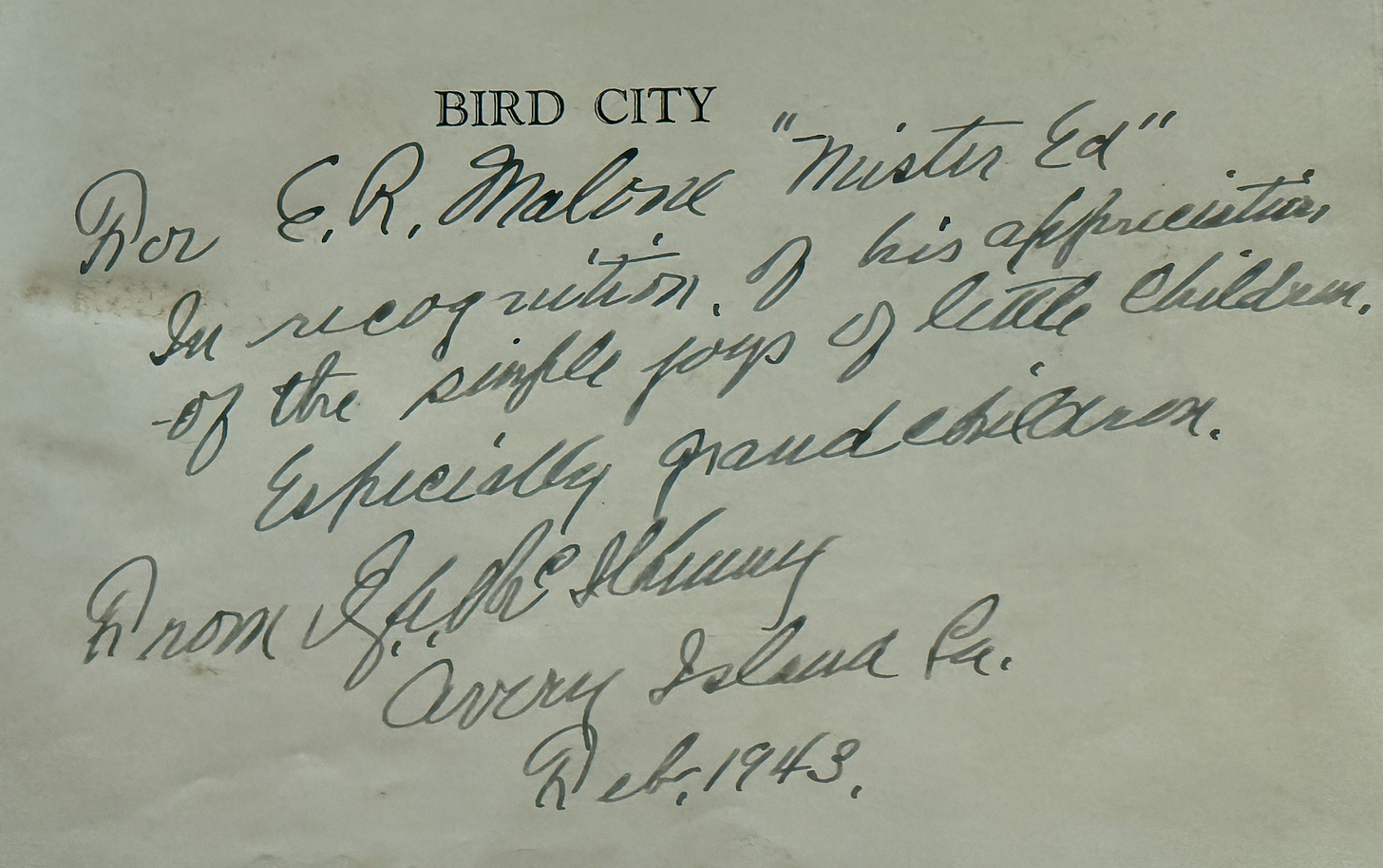

Because my family’s copy of “Bird City” has the following personal note written to my grandfather and indirectly references my father as a child, I have kept the book in our main office.

Yesterday, as I was organizing, I began to read. The preface stopped me in my tracks. It spoke directly to my own heart and soul as I consider my age and mortality.

As the book is out of print, I am copying out that preface - it is as relevant and timely now as it was then:

Bird City Preface, by E. A. McIhenny:

“Now that I am well, along on the downgrade of an active life, largely spent in the open, in close touch, always with mother nature - that dear old nurse, who has been through all my years, a kindly teacher and loving friend; who has ever been my guide and inspiration; who has taught me to love all living things, and to interpret the language of them; who has dispelled much evil from my brain through her sweet example I realize more and more as I approach oblivion, that her teachings, which in my thoughtless youth, I considered a gift to me, were but alone, and must be handed over by me to those who are growing up around me, and who’s taking where I leave off, will carry on more peacefully, through their lives with nature’s guidance, to the same eternity into which I am sinking.

I have always looked up upon life as a great adventure, the chief zest of which has been the library to learn by personal experience; but one may derive considerable profit, and learn the riddles of life much more easily by heading the experiences of others; if these experiences be truly told.

I know we are to die, in fact, it is the one thing of which we are sure. All future things are but guesses, and most of the time we guess wrong. Now, and then we put a timid question to ourselves as to our destiny, but as no one has ever come back from the hereafter to tell us the truth about it, our questions are unanswered. We are taught many weird tales of what the future holds in store for us, but they are but tales to give peace to our superstitions.

Nature’s teachings, however, however, are never tales. To those who understand her, she speaks only truth. Her laws are just laws, and she shows no favoritism to any of her children. Since the time of creation until today, nature’s laws have not changed, and man with all his cunning has never completely altered a single one of them.

Let those who would live happily and approach the inevitable with a peaceful mind, take heed to nature’s teachings, live a natural life; watch, listen, and think; for the more of these three things you do, the sooner you will realize that your happy, natural fate, lies solely in yourself and your life on earth, and not in the future.’

As I read the above, my mind flitted to McIhenny’s contemporary, Aldo Leopold, whose slim journal of his life living on his farm in Wisconsin, titled: “The Sand County Almanac,” inspired generations of ecologists.

Both McIhenny and Leopold’s writings and works paralleled each other, yet there is no record of the two meeting or collaborating. In my mind’s eye, I imagine that they did meet and that they must have read each other’s books. The writings of these two naturalists often seem written as if each shared a common vision during their time upon this earth. I like to imagine that they avidly read each other’s works and am reminded that the modern ecologist and the science of ecology directly evolved from the work and traditions of naturalists and natural history of that era.

Although the first section of “The Sand County Almanac” chronicles the seasons on Leopold’s Wisconsin farm and is written in a similar style to “Bird City,” it is the latter section of Leopold’s book that made a lasting impact on America.

In it, Leopold lays out his philosophy of the “land ethic.” Here, he argues that humans should see themselves as members of a broader ecological community rather than as conquerors of the land, and that the ethical responsibility of humans must extend to soils, waters, plants, and animals.

This book, more than any other, influenced my thoughts on owning land and homesteading and, in principle, has partially guided me throughout my life’s journey.

In some ways, Aldo’s writing now seems dated, as modern ecologists define ecological issues on a global scale. The concept of “global change” is all the rage. The importance of local diversity and the role of the small farm are ideas that have been largely lost to time and the scientific method. This is an error, as it is down at the local level that nature often needs the most protection. The land, the natural world, is where we humans find peace and a sense of community. Community with nature is just as crucial to the human condition as human interactions are. Being grounded in the earth and part of nature, the natural world brings solace to the human heart. The wind, energy, earth, and sky - as animals, as humans, we crave these physical elements.

Every homestead or small farm established to work with the land, rather than against it, contributes to that healing process. Each suburban home that avoids chemical pesticides and fertilizers on the lawn and shrubs saves countless insects, birds, and other wildlife. This is the local habitat that we as individuals must cherish - this is what feeds our collective souls.

The Earth will heal itself if we step aside and simply stop the chemical and physical assaults on its crust. Jill and I have rehabilitated many a small farm, and it is always a shock how quickly Mother Nature returns ruined land into her fold. Whether it be the crumbling of old houses and barns, or the earth scarred by the loss of topsoil that soon grows an abundant forest. The truth is that the Earth will heal. Maybe not in our generation, but Mother Nature takes back her own. It may not be the same or have the same diversity, but it will heal.

Likewise, protecting the wild spaces, the fertile farmlands, and the indigenous lands from overdevelopment all play a part in maintaining our local well-being. "We are the world" may sound wonderful, but truth be told, we can save our world by focusing on our local world. In doing so, we must also save ourselves.

One of the most significant issues with “open borders” is that our cities and developed spaces soon gobble up the most cherished spaces and wildlands. We don’t need more people pushing into our vulnerable habitats. We don’t need more agribusinesses plowing over forests and prairies to grow non-nutritionally dense food for the masses flooding into our country or to feed other nation-states. Our cultural identity lies not just with its people but with the very land we live on. With each million more people filling up America, the wild places dwindle. Yes, the land will heal itself eventually - but at what cost to our future generations?

Viewing ecological issues only at the global level lets the polluters of our land off the hook, as the world’s eyes focus on carbon credits and the atmosphere, and not on what is happening to the very soil we live on.

This is the beauty of the Make America Healthy Again movement: it isn’t just about its people; it is about the earth under our feet.

To leave the digital world and focus on the local brings great peace to the soul. The ability to step away from the world of man and step into the healing rhythms of nature, the cycle of life, is what McIlhenny writes of:

Let those who would live happily and approach the inevitable with a peaceful mind, take heed to nature’s teachings, live a natural life; watch, listen, and think; for the more of these three things you do, the sooner you will realize that your happy, natural fate, lies solely in yourself and your life on earth, and not in the future.’

-McIlhenny

Finally, I leave you, the reader, with one thought. Do not take for granted the luxuries of modern life and the digital world. For they are but a dream brought to you by someone else. Instead, realize that happiness comes both from within your spiritual world and because of the natural world, and each of us makes our own heaven or hell here on earth.

In closing:

There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace. To avoid the first danger, one should plant a garden, preferably where there is no grocer to confuse the issue. To avoid the second, he should lay a split of good oak on the andirons, preferably where there is no furnace, and let it warm his shins while a February blizzard tosses the trees outside. If one has cut, split, hauled, and piled his own good oak, and let his mind work the while, he will remember much about where the heat comes from, and with a wealth of detail denied to those who spend the week-end in town astride a radiator.

-Aldo Leopold. From “A Sand County Almanac”

Your reflection on the sacredness of Mother Earth is necessary for all of us to contemplate. The Native tradition teaches to make decisions knowing they will have impact unto the seventh generation. The people of the Amazon Rainforest were telling Zach Bush of their crisis of needing to have healthy fish and water as well as soil; they don't have grocery stores. Their plea is the same one so many have due to poisoning of the air, water and soil. Can't eat money if there is no food.

In a hundred years the family tale of Robert Malone the scientist turned freedom fighter and international lightening rod will be told... although the story doesn't yet have an ending! It is hard to imagine what the context of that fight to the current world will look like far in the future. Of course it is another thing we will never know!