One Sovereign Man's Overview of History

James Hickman takes us on a journey from the Paleolithic to the present

Simon Black, as James Hickman is more commonly known, is the Founder of Sovereign Research.

He is an international investor, entrepreneur, and a free man. His daily e-letter, Sovereign Letters, draws on his life, business and travel experiences to help readers gain more freedom, more opportunity, and more prosperity.

Hickman is a lifelong entrepreneur and investor that’s traveled to more than 120 countries on all seven continents. In addition, he’s started, invested in, or acquired businesses all over the world.

He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point and served in the US Army as an intelligence officer during 9/11 and the war in Iraq.

Hickman founded a South America-based agriculture company that has become one of the leading producers in its industry. A few years ago, he acquired a prominent retail brand in Australia, purchasing the business from the former 1980s era rock star who founded it.

His other business ventures have included starting a boutique, private investment bank that boasts some of the highest levels of liquidity and solvency in the world, and investing in companies from Colombia to Uzbekistan. He also serves on numerous Boards of Directors, and presently serves as Chairman of company listed on a major stock exchange.

Writing under the pen name Simon Black, he has also written extensively on business incorporation and tax residency establishment in Puerto Rico, and is a proponent of investing in gold and silver as a hedge against inflation.

He is also a prolific writer on topics ranging from second residency and citizenship, Golden Visas and portfolio diversification, to estate and retirement planning, asset protection, tax optimization and US Opportunity Zones.

Introductory Session, “Total Access” meeting, Mexico City

November, 2022

James Hickman

I will start this essay with some big picture ideas, as I often do, hoping to synthesize a lot of things that I have been discussing in prior presentations. And, as is typical for me, we'll start by going back in time. This time I want to start by focusing on events which occurred around 7,000 years ago in the Peloponnesian Peninsula region of ancient Greece. Now, this is so long ago. This is thousands of years before Socrates and Aristotle.

A really long time ago, there was a tribe of unknown origin who came over into the Peloponnesian Peninsula from the Levant. They were hunter gatherers and nomads, and they came down and they settled here. This was really not long after the agricultural revolution which is formally referred to as the Neolithic Revolution.

Genetic markers in modern populations indicate the Neolithic migrants who brought farming to Europe traveled from the Levant into Anatolia and then island hopped to Greece via Crete and then to Sicily and north into Southern Europe. Credit: Modified NASA map. For further details, please see “Study indicates Neolithic people from Near East migrated to Europe via island hopping”.

The term “Neolithic” comes from the Greek, Neo for new, lithic (or lithos) for stone. So therefore, it was really that the agricultural revolution was essentially the last part of the Stone Age. And the reason why the Stone Age lasted for so long, literally millions of years, is because early human civilizations at the time were all hunter gatherers. And as hunter-gatherers, they never put down the roots of civilization. They didn't have the capacity to build new technologies and things that actually propelled the species forward, because they were constantly getting up, moving, and going to a new place. It was the agriculture revolution, the neolithic revolution, that actually made it possible to propel human beings out of the Stone Age and into the next, which was the Bronze Age.

Now consider this tribe which has arrived in the Peloponnesian Peninsula by island hopping, not long after the start of the agriculture revolution. They come across a place. There's abundant water. The soil was very fertile, and on a little hillside, about 900 feet above sea level, they built a fortress. They had 360 degree views of the surrounding valley. It was a pretty strategic location. They could see and defend against any potential oncoming, invading enemies. They were only about 12 to 15 kilometers from the coast, so they were protected from storms, but at the same time, they were only about a half a day's journey to the coast if they needed to get there. So it was a really, really good place, and they built a fortress there. That fortress, in time, became a great city and eventually a great power in the region.

These people became known as the Mycenaeans. The Mycenaeans were the Greeks before the Greeks. Again, this is thousands of years before Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, and everybody like that, the historic Athenian Greeks that we all know and have heard of, and this was a civilization that really had a lot going for it. They had advanced technology. They had a writing system which current scholars call Linear B script, and it was one of the first writing systems in the world. It was actually a very interesting writing system in that it was unlike Egyptian hieroglyphics, which were purely pictographic; in ancient Egypt they had a symbol for each specific noun, and so Egyptian hieroglyphics were basically a very noun-heavy writing system. In contrast, Mycenaean Linear B actually used symbols to convey ideas.

For example, they had a symbol for horse, and a symbol for donkey, pig, and things like that. But they also had phonetic symbols, like we do in a Latin or Cyrillic alphabets, so Linear B was a really advanced writing system, but they had far more than just writing systems. They had advanced mining technology, metallurgy, and smelting. They figured out how to melt tin. They figured out how to melt copper with tin and turn that into bronze, and this is really what got the civilization out of the stone age. The ability to make bronze, to create better, more superior tools that helped them to continue advance their civilization. They had advances in construction technology, advances in military equipment, weapons, tactics, agricultural advances, and all sorts of things that really made them the power that they became.

But around the year 1180, 1200 BC, the Mycenaeans just disappeared. They completely disappeared from history. Archaeologists have now have been able to piece together quite a bit of information from remaining relics, and have learned a lot of things about their civilization. We know that their cities were burned, their temples were razed, their palaces were destroyed. Mycenaean cities essentially were entirely vacated, and thousands, tens of thousands of people in this area just disappeared from the cities and began nomadically roaming elsewhere. There is a fair amount of archeological evidence that exists, but there's also a great deal of legend, and of course there is Homer. Homer tells us stories of the Mycenaean civilization, the most famous ones obviously being the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Now, a lot of what Homer has to say is complete garbage, and we all know it, right Fantastic stories about monsters, witches, and all these things. But to be fair, that's not so different than what we see in today's modern media. Filmmakers are notorious for taking an absurd amount of dramatic license. For example, in one of my favorite movies, Amadeus, the movie promotion literature literally says "Everything you've heard is true." Actually, almost everything you hear in the movie is completely not true. Salieri didn't kill Mozart. All these things are a sort of fiction that they're pedaling, but they do it because it's so much more entertaining. They know they need to entertain their audiences, and they come up with these ridiculous stories of intrigue, murder, and so forth because it makes the movie more interesting.

This type of poetic exaggeration was also normal in ancient civilizations. The works of Herodotus had lots of fiction, and we can see this obviously a lot in the Old Testament, but it's all based on a true story, right? In the Bible, there's an incredible amount of historical gold. For example, in the Bible (Old Testament), they talk about all these different tribes and civilizations that did actually exist: The Amorites, the Canaanites, and the Israelites.

There are so many of these examples. Of course, there was an exodus. Of course, the Israelites were enslaved in Egypt, and they had a ground exodus. But did a guy really pull out a wooden staff and part the Red Seas? Probably not, but it's grounded in truth. It's grounded in real, factual history. It's based on a true story. Of course, the entertainers and storytellers, being what they were, had to come up with more interesting fiction. "And then he pulled out his staff and parted the Red Seas," but it doesn't make the rest of it untrue. We know, for example, that most likely there actually was a Trojan War. The ancient name for Troy was Ilios. Hence, why Homer’s book is called the Iliad.

Troy was built in an area of modern day Turkey called the Dardanelles. The Dardanelles have long been one of the most, if not the most, strategic locations in the world, because they basically control the trade route between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, and this was the most important place that you could control in the ancient world, because you've got a lot of mining that's taking place. The products of that mining activity had to pass through the Dardanelles. For example, to the East as far off as Afghanistan, Persia, all the way to the Neo Babylonian and the Syrian empires, all of that trade had to go through the Dardanelles. Meanwhile, to the West you've got the entire Mediterranean, the Levant, North Africa, and everything else, and the Dardanelles are right in the center of those trade routes. If you control that, you really control global trade. There was clearly a conflict associated with this bottleneck controlled by Troy just waiting to happen. There had to have been, because the Mycenaean civilization had become the most powerful force in the Mediterranean.

Troy controlled all the trade into the Mediterranean. As a consequence of their strategic location, Trojans not only controlled the entrance to the Black Sea, but they also controlled the most important mineral resource in the ancient world, which was tin. Tin, today, is like nothing. Who cares about tin? But in the ancient world, it was so incredibly important because it was essential for production of Bronze. In the ancient world it was as important as oil is today, or lithium will be tomorrow. So because of that, when there were issues with the tin trade, and in the tin markets, in tin supply and tin production, and this caused havoc across the ancient world. Most of the tin was being mined in places like Persia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and so it had to come across that route, through the Black Sea, through the Dardanelles. Meanwhile, the Mediterranean is where the copper mining is happening.

The copper was coming out of Cyprus and so forth, and the Mycenaeans controlled that, so there was a lot of reason why there would've been a conflict between these two civilization. Therefore, the war between the Mycenaeans and Troy most likely actually happened.

This probably didn't.

The horse and all that ridiculous thing, and the shot through Achilles’ heel and all, that is the entertainment part, and it’s very entertaining. It's really entertaining when you get into it, but a lot of this was probably made up, or when they make up these stories, they make them up because they're parables or they are symbols for other things. For example, in the ancient world, horses were often used as a symbology for a navy, a naval fleet. Ships were often known as sea horses, and so it could have been some acknowledgement of the Greeks’ superior navy and their naval forces. Who knows? But most likely, it wasn't a bunch of guys sitting inside of a horse waiting to raise a city.

Then, we have the Odyssey. Coming after the Iliad, which is the story of the Trojan War, we have the Odyssey, and that's a very familiar theme. The theme of the hero who has to endure a perilous voyage home. A voyage filled with a lot of danger and adventure, because the hero, the war weary veteran who just won the war and saved the people, now has to make his way home.

If you haven't seen Star Trek IV, it is very much like the Odyssey, it completes the story arc from the preceding Star Trek movies with a perilous travel home. Of course, it's filled with all sorts of crazy adventures. That's basically what the Odyssey was. It's just a story arc, and if you think about it in the same way that we look at movies today, where we have entire movie franchises with 37 different movies and so forth, that's kind of what the Iliad and the Odyssey were. Just a franchise, and they were making it as entertaining as possible. This concept of the homecoming story, the Voyage Home, is a very, very familiar one, and the Odyssey is a prototype. You have Odysseus leaving Troy. He had just helped win the battle and sack the city, and now he must return home to his wife. Of course, he gets kidnapped by a cyclops, and he is constantly being seduced by beautiful women. Of course it's only Odysseus, it's never anybody else on the crew. It's only the hero with all these beautiful women constantly falling in love with him.

Then, he goes from one place to the other, and then he finally makes it home where his wife, Penelope, is being courted by all these suitors that want to plunder his kingdom, the kingdom of Ithaca, for all the wealth and money which awaits his return. He goes home, disguises himself, slays all the suitors, and we have a big, happy ending at the end of the story, and this becomes one of the greatest stories of all time. It could very well be based on a true story. Is it possible that there is a high ranking king, a veteran of the Trojan War, who had a lot of adventure on the way home, and had a difficult time making it back across the Mediterranean? Sure, of course that's possible. It's actually quite likely, given what travel conditions were in the ancient world.

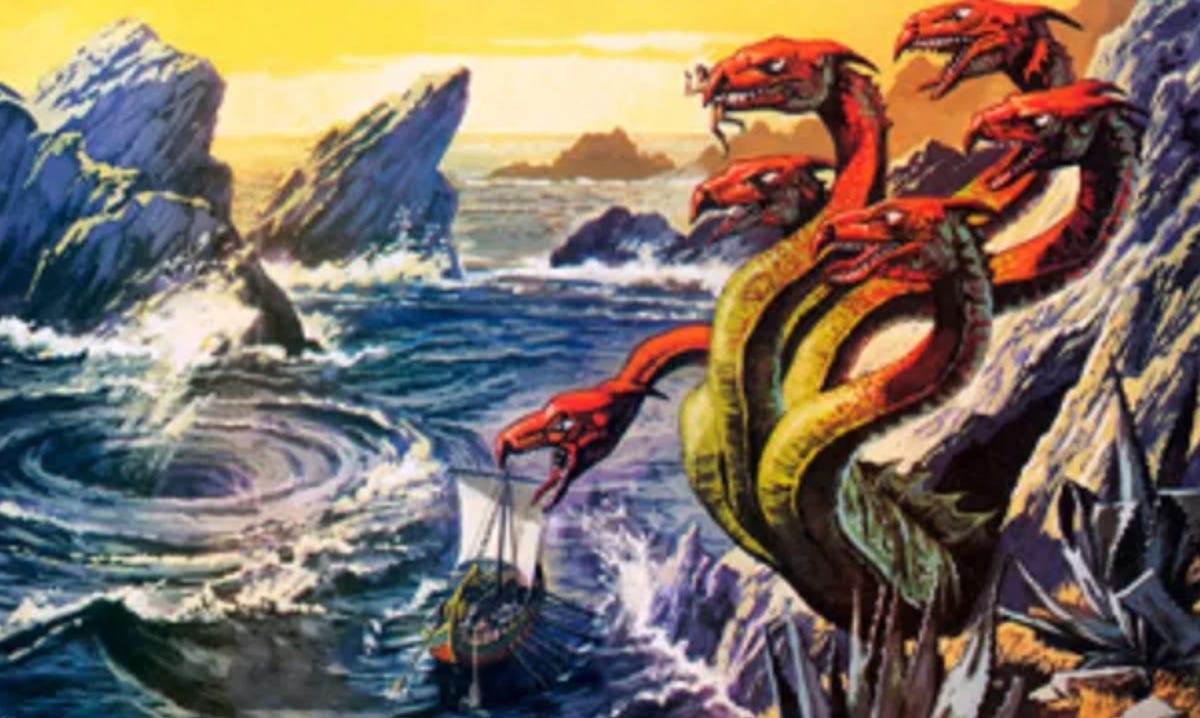

Did Odysseus’ return actually involve monsters, sirens, witches, and so forth? No, probably not. But those plot twists makes it very entertaining. One of the very important and famous stories from the Odyssey is a story known as the parable of Scylla and Charybdis. Scylla was a mythological six-headed monster, and Charybdis was a whirlpool that would destroy every ship that went through it. According to Greek mythology, nobody had ever been able to navigate the Charybdis properly. This plot twist may very well have been based on a true story, because modern day historians and geographers have found that off the coast of Sicily there is a place called the Strait of Messina, where there actually is a giant rock. Inside that rock, there's a cave, and inside that cave, according to the mythology, there lived a six-headed monster.

I turns out that there actually is a rock with a cave at the Strait of Messina, and across the water is a whirlpool. Now, the whirlpool, realistically, is not really that dangerous, and it's only going to be dangerous for really small ships. Everybody else is like, "Oh. It's no big deal." But of course, to improve the story, they have to make a big deal about it in the Odyssey; "Anybody that goes through there is going to get destroyed, and everybody's going to die," and so forth. And, according to the Odyssey, Odysseus was warned in advance-"Listen, you're going to come across this place. On one side, there's a rock, and inside that rock, there's a cave. Inside that cave, there's a six-headed monster, and six of your men are going to die if you go through there, and on the other side is this Whirlpool. The whirlpool's going to crush everybody, and you're all going to die if you go through the whirlpool."

Now, Odysseus was an expert, right? At first, like many modern experts, he was completely dismissive about the risk. He said, "Come on. I'm an expert. There's no risk here," and he denied, denied, denied. He said, "No, there's no risk here whatsoever." Then, eventually he finally realized that there was a risk, he switched to "Okay, fine. There's a risk, but the whirlpool, it's transitory, and we don't really need to worry about it" and insisted that he was going to be able to properly navigate both himself and his crew through this risk. It wasn't going to be any problem. Finally, he eventually realized "Oh my God. This is actually a really big deal." And at that point he was forced to make a very difficult decision. He would have to choose between the two evils, and he chose the lesser of the two. He chose, of course, Scylla, the six-headed monster.

In Odysseus mind, the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, and he would rather lose six of his guys than all of them. He'd rather lose six of his guys than the entire vessel and everything on it, so he chose the lesser of the two evils. This famous parable may well be based on a true story, because the Straits of Messina actually do exist. There's a whirlpool. There's a rock, et cetera, but they made up this whole thing about the six-headed monster but it doesn't change the parable, this very important parable of finding yourself forced to choose between two evils, and you must choose the lesser of the two.

This is essentially a situation that we find ourselves in today. We have a couple more experts to consider here. I am turning now to the chairpersons of the Federal Reserve in the United States since the early-2000s.

Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, who took over from Bernanke, and my main man, J. Powell, who took over from Janet Yellen. I'm sure these are all very nice people. I mean nothing against anybody, in terms of who they are, their character, and so forth. But it is, and I think actually if you guys came to the event in Austin, one of the things I actually found so interesting about Dr. Malone's remarks as he was talking about Fauci, was how Fauci wasn't really the problem so much as he is a symptom of the problem, as it was the system itself which was the problem in that it that enabled somebody like that to be able to take this control over everyone and everything. That, in a way, is really what this Federal Reserve situation is. It's not the individuals here.

It's the system itself that has been established since 1913, since they passed the law establishing the central bank in the United States, and ever since then, they've anointed this organization to say, "You're going to run everything in the economy. You have supreme executive authority to do whatever it is that you want to in the economy." And when you step back and consider that, you have to conclude "That's actually insane." It's insane to think that a couple of people can sit in a room and think that something as complex as a 20 plus trillion economy that has literally trillions and trillions of different economic units, businesses, transactions that occur. Every single transaction, every day. When you travel, when you buy food, when you fill up your gas tank, think about the trillions and trillions of those transactions that take place in a given year.

And to think that a handful of people are going to sit in a room, and they're going to push a button and just everything's going to be optimized, it is clearly insane to think that anybody can control that. It is literally insane. But that's the system that we have now with the Federal Reserve. These people are just representative of the system. Take for example what they did way back, going back to the GFC (the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2008), right? Back in 2008, when the world was coming to an end because all the banks were failing and so forth, and so Bernanke, he's actually credited with saving everything. Everybody says, "Oh. He saved the world. He saved the economy." No, he just created a really big mess for everybody else that followed him. He's the guy that slashed interest rates down to nothing. He went to Capitol Hill, testifying in front of Congress to justify this. And then the Federal Reserve printed gobs and gobs of money and injected it into the banks and through that into the economy.

Many actually made a joke about it, saying, "A trillion here, a trillion there, and pretty soon it adds up to real money." Remember that the conventional wisdom was that this was just no big deal, and so they kept interest rates low after he left. Then Janet Yellen took over as head of the Central Bank. They kept interest rates at almost nothing for a really, really long time. Of course this would have consequences, yet the whole time (just like Odysseus) they kept saying "No, no, no. It's going to be fine. It's going to be fine. We're the experts, and the experts have decided it's going to be fine. There's nothing to worry about." Then, Janet Yellen steps down. Jerome Powell comes up. When inflation came up, these were the same people that were saying, "Inflation? What are you talking about? Inflation? Come on. You're crazy. Ah, you're crazy. Inflation. Come on." Then, eventually they came and they said, "Okay, all right. Fine. There's inflation, but it's transitory."

Then they abandoned transitory, and they said "All right. We're going to do something about it. I swear to God we're going to do something about it, but later," and they continued saying this November, December, January, February. They stubbornly continued saying "We're going to do something about it. I swear we're going to do something about it," and then they finally did. I honestly believe that they honestly believed that with the first raise in March of 2022, when the rate hike came, that everything was just going to be okay, and inflation was just going to dematerialize, and they were going to get to say, "See, I told you it's all fine." Then, it didn't, and they go, "Oh, shit," and they did it again, again, and again. Inflation wasn't coming down, and now the Fed position has switched from this confident, almost James Bond like "I got this. I got this. Don't worry." Now it's like, "Oh my God. We have to raise rates. The world's coming to an end. We're going to do something about it, no matter what the costs," and instead of this buttoned-down, cool, professional, 007 monetary policy, now it's turning into this ultra panicky, hair on fire, monetary policy.

Quite interestingly, now the inflation numbers came out just yesterday. They went from 8.2% to 7.7%, and everybody's singing the Hallelujah chorus about this now, that it's this big deal, but that's not really how it works. If you'll forgive me a little bit for going back to high school economics, in case people slept through that course, we all know that price is basically the intersection of supply and demand. This is very crude, and a lot of this is obviously used in theory, and you have elasticity and all sorts of things.

But in brief, sure, we've got supply and demand. So we've got the demand curve and the supply curve, and price is where the two meet. Well, what do they do? If you think back to 2020, what the Fed and the US Government did here was they said, "Everybody stay home. Everybody stay home. There's a virus on the loose, Stay home. Sit in your basement like Joe Biden. Don't come out. Don't go outside. Don't go to work. Stay home. Get fat. Eat McDonald's. Drink booze. Take your drugs. Watch your kids as their educational development regresses substantially, but whatever you do, don't go outside. Don't get fit. Don't get healthy. Be afraid. Watch all the fear porn on CNN, stay home, and don't work," so obviously what you had, as a result of that, was a decrease in the amount of goods and services.

Consequently, we have seen a sharp decrease in supply of goods and services if we look at aggregate supply across the entire economy. Basically, we have an aggregate decrease in supply, but then what they did is they made it rain money. The central bankers came out, and they exclaimed "Free money for everybody", and so they printed lots and lots and lots of fiat currency, and the government gave everybody lots of money, and they came out with the most creative ways of doing it. They said, "Oh. We're going to do PPP (purchasing power parity)." Oh, but it's a loan. It's a loan, but it's a loan that doesn't have to be repaid, so it's free money. Then, they just said, "You know what? We're just going to put money in people's bank accounts. We're not even going to pretend. We're just going to put it right in your bank account."

And they came up with the most creative ways of doing it. They gave states the money. They gave foreign governments money. I mean, it was just ridiculous amounts of money, and so obviously that stimulates demand. This is when we started to see issues with the supply chain. We started seeing people take the position "Oh. Well, I'm trying to order this, but it's not available," whether it was microprocessors, shoes, and then cars and all these things. Lots and lots and lots of problems with supply chains.

Now you've got a decrease in supply and an increase in demand, and you end up with a new price. Wow, what a surprise. We have higher prices. This is high school economics. It's not complicated. So what are they doing now? Well, with the interest rate increases, what they're trying to do by raising rates is they are trying to decrease demand, which is working, right? Because when it's more expensive to borrow money, people borrow less, which means they spend less, which reduces demand. That's the theory and, in part, that's actually working. But what they're also doing is that the Fed is also kind of decreasing supply as well, because you've got a lot of businesses that are really over leveraged, a lot of businesses that have a lot of debt.

All of a sudden, the business model for these leveraged companies depends on being able to continually refinance that debt, and suddenly they can't refinance that debt anymore because capital is more scarce, the rates are a lot higher, and these companies suddenly face bankruptcy. As a consequence, you have people that are going out of business, and when companies go out of business or employees get laid off, there is less supply, because there are fewer people and fewer business producing goods and services. So, sure, you have less demand, but you also have less supply. As a result you follow intersection of the supply and demand curves and arrive, more or less, at the same price. Maybe a little bit less, but not a material difference in your price levels, which is why after all of this, we really haven't seen too much in terms of a decrease in our price rates.

If you think about the Federal Reserve's key interest rate, they have increased it literally by 75x, from 5 basis points to 375 basis points, and yet inflation has hardly budged. A 75-fold increase in their key benchmark interest rate has resulted in very little reduction in price levels. The other part of this that's important is that you can't really fix this until you fix the supply side. There are a lot of things that are creating problems in supply. One of those is the lingering issues in the labor market. The labor force participation rate still has not recovered. Labor participation is still much lower than it was years ago. Because of COVID and a lot of other issues, people just said, "Screw it. I'm out," and they retired early and they quit the workforce.

Meanwhile, you've got a lot of Gen Z making interesting occupational choices. They're not going into truck driving, and being forklift operators, farmers, and a lot of these things. Instead, they're professional video gamers on Twitch, and they are posting butt selfies on Instagram for a living, and all these sorts of things that don't actually contribute anything meaningful to the economy, right? And so you've got critical occupations that are being unfilled at a time when all these people are retiring, the labor force participation hasn't recovered, so there's still a lot of issues in the labor market, and that adversely impacts supply.

As if that was not enough, there is a big reversal in the globalization trends. For the last 30 years we have seen an era of almost unprecedented peace and prosperity, certainly in modern history, where everybody had an incentive to just get along and play nice. Sure, there were occasional flareups, and you had terrorist groups and things like that here and there, but among sovereign nations there was a great deal of cooperation. You had even China, Russia, and everybody just kind of, more or less getting along because it was in everybody's interest, because they were making so much money.

Who would want to screw that up, right? Everybody was making a lot of money, and now that's reversed. Now you have countries that are essentially saying "Well, before we were doing win-win deals, where we all got a lot of value out of the arrangement, but now, because of our geopolitical conflicts, now I want to block you. Now I'm your adversary. Now I'm going to take steps specifically to try and block you gaining. Therefore, I only want to do a win-lose deal. And if I can't do a win-lose deal, then we'll all lose, and I will do a lose-lose deal," which is the opposite of the objectives of capitalism.

Capitalism is about win-win deals, where you create value and everybody gets to win, and in this way it propels everybody forward. What is happening now is the opposite of that, where you end up doing lose-lose deals, deals that are just remarkably stupid. Unfortunately, we are seeing this quite often, with even the Russian sanctions that have basically resulted in sky-high oil prices that are actually benefiting some countries at the expense of others, like the United States. We're seeing trends with re-shoring, where people realized after the pandemic that people were getting things manufactured in China instead of the USA. Policy makers said, "No, we can't do that anymore," so now we're going to bring that stuff back to the United States, where we can't find labor, and the cost structure is so much higher." So these policies have created still more damage to the supply chain problem.

Then, you've got rising expenses, even for people that still manufacture overseas in places like Bangladesh, India, and different places like that. Now, even those costs are rising. Offshoring was a force that, for a long time, had constrained inflation, but now that force to keep inflation down is going away. This is also negative for supply, but one of the biggest issues by far is energy. Let's just say that a man reaps what he sows, and I don't mean to pick on any one person. It's not polite to pick on people who have dementia anyway, so I'm not going to do that.

But what I will say is these people have, from day one, targeted the fossil fuel industry, and the outcome is exactly what they have intentionally engineered. Now they're pissed off about it, and now the POTUS is wagging his finger at everybody, saying, "You evil oil companies". Well, this is the outcome that he was seeking. He wanted them to produce less. He, and the interest groups that he represents, wanted to put these guys out of business. He wanted to make life difficult for them, which is why the US Government created a mountain of regulations, which is why you are required by law to issue concessions and leases on federal land. It's not like optional. It's required by law. They just won't do it, and this has lead to one of my favorite delusions. He was wagging his finger again at his favorite target, as always, Exxon Mobil. He says, "Exxon Mobil makes more money than God," which is actually a really bad analogy, given the pitiful state of Vatican finances. I think most people, at this point, make more money than God if you look at it on a free cash flow basis. The Vatican is hemorrhaging money. Anyways, what he goes on saying is, "I'm going to make sure that everybody knows how much money Exxon makes," and you've got to go, "Dude, it's a public company. They report their earnings. Everybody knows how much money Exxon Mobil makes, because they're required to report their earnings." Exxon already makes sure that everybody knows how much money Exxon makes.

But Biden doesn't even understand the basics of financial markets. It's kind of embarrassing, but what we are now living through is the result of this ignorance. The energy concerns, the energy issues that we have, those are not accidental. There are so many things that the Biden administration has deliberately done to create this situation. Whether this was the intended outcome or not, it doesn't matter. This is exactly what they've engineered, and again, not to just pick on one person, those advocating for these policies are all the people that are now in Egypt at the Cop27 (The United Nations Climate Change Conference) nonsense, where they all pretend that apparently saving the world from climate change depends on gender identity and all this stuff. They literally have an entire day set aside at Cop27 as gender day, because apparently it's gender studies that are going to lead us out of a climate crisis. It is so completely insane.

There's not a single word about nuclear energy anywhere on the Cop27 agenda. We can't talk about real solutions that actually work, but we're going to talk about gender identity, because that's apparently going to solve a climate crisis. What we have here are major supply issues, long-term consequences, long-term implications that make supply a lot more difficult to come back to normal. And that is something that I believe is going to keep inflation elevated for some time, and this takes us back to what central banks are trying to do; tackling inflation by raising interest rates, and raising interest rates, and raising interest rates. Those increases in interest rates will have consequences.

One of those consequences is that higher interest rates adversely impact heavily indebted entities of any kind, whether you're talking about individuals, businesses, and even sovereign governments. And you've got places like Greece, like Japan, and so forth, that really are in a lot of trouble if rates continue to increase and then you have the United States, where the national debt has basically doubled over the last 10 years. It's been growing at an astonishing rate. In fiscal year of '22 (which just ended on September 30th, about 6 weeks ago) according to the government's own financial statements, they spent $680 billion in interest during fiscal year '22, and that's when the average interest rate was nearly at a record low. Now we've got rising interest rates.

By the way, I have to say something about this interest rate number. They pedal a lovely fiction on their financial statements, where they say, "Oh, but that number doesn't actually matter," and they try and report a lower number that they call the net interest, and the difference between this number, which is gross interest, and the net interest goes as follows: "Well, some of the interest, we actually pay to ourselves." So for example, we give $800 billion to the Defense department, and the Defense department doesn't go and waste all that money immediately. They waste it over time, right? And so the money that they haven't wasted yet, they put in treasuries, so they earn a little bit of interest. The Defense department takes money from Congress and then they go and actually invest it back in US treasuries, and they get a little bit of interest, and so the government likes to pedal a fiction. They go, "No, no, no. Well, that amount doesn't matter," and you go, "Well, of course it matters, because the defense department still gets that money. They still get the interest, and then they spend that money," so it's not like it's just free money. The fact that the government sometimes borrows from itself and pays interest to itself doesn't mean that it's not actual real money that is owed and has to be paid, and then later gets spent or wasted. So this money actually matters, and that number is $680 billion, and that's before we factor in significant interest rate increases.

If we look at 10-year treasuries, actually, if you go back 10 years ago, just 10 years ago, the 10-year note was almost nothing. I'm going to just thank Pelosi, right? Nothing, right? It cost nothing. The 10-year treasury literally cost nothing. It paid nothing, and now you've got a lot of these 10-year treasuries that were issued way back when at nothing, and now that all has to get refinanced, because when the bonds mature, the government has to pay it back, but of course they never pay it back. They just go and borrow from somebody else, right? Sometimes even the same person. They go, "Okay. We're just going to refinance it," but they refinance it at a higher interest rate.

Whatever the current interest rates are, they refinance it, so you go from half a percent to 4%. That's a really big difference. That's a really, really big difference, and so if you were to refinance a lot of this debt, you're talking about easily shooting past $1 trillion dollars and even getting to $2 trillion just in the amount of interest that you have to pay, and that doesn't even take into consideration the additional debt that they take on year, after year, after year. These people are bragging because they said, "Oh, the deficit was only $1.4 trillion this year," and they think that's a cool thing. They think they've done a great job because the deficit was only $1.4 trillion, and so by the Treasury department's own projections, the national debt will continue to grow at an accelerating rate, higher and higher and higher.

They're going to be paying these new higher rates. Every year, roughly 20% of the US public debt has to be refinanced, because the average maturity for US public debt is about 5 years, a little bit over 5 years. That basically means every year, 20% of the debt has to be refinanced, but it's being refinanced at higher and higher rates. And so you can understand the problem here is that very, very quickly the amount of interest that the treasury department is going to have to pay is going to skyrocket, and pretty soon servicing the interest will edge out all other spending. That's a really dangerous scenario, because if the US government were pushed into default, it would create a financial apocalypse. Everybody, nearly everybody, would fall.

Every bank, every corporate treasury, every corporation that has US treasuries (which is pretty much every major corporation), sovereign governments, foreign central banks, the US Central Bank, everybody would suffer immeasurably. Financial markets, stock markets around the world would crater. Central bankers are intelligent people. They understand this risk. They understand that you cannot push the leading sovereign government in the world into a state of insolvency where it's paying so much an interest that it cannot afford to do so any longer. That is an actual risk, and they know this, and so therefore there is a level that they know they just can't go beyond in terms of their interest rate hikes. They all know this.

And even if you take the federal government out of the equation, you're talking about a lot of very heavily indebted businesses, state governments, et cetera, as well as a lot of pension funds. There's so many issues here because all these entities got so accustomed to zero interest rates for so long, they built up portfolios that depend on all these things. We've already seen this in the UK, if you guys remember just over the last several weeks, where they had a major issue with the Pound, the UK government bonds and guilds because of pension fund issues there, because they have so many of these funds that they basically had to take on larger and larger risks because of the interest rate environment. So this is a real issue, and they know this.

Therefore, if the central banks (and the Bank of International Settlements) have to choose between continuing to raise interest rates in a desperate attempt to battle this chaotic adventure and associated inflation, or we're just going to accept a certain level of inflation, not at the level that it is today, probably less. We're not talking like seven, eight, nine percent. Maybe they get down to five-and-a-half. I think that they'd consider that probably a big victory. If they can stave off a major financial apocalypse, they're absolutely going to choose inflation, because it is the lesser of the two evils. This is, in a way, a major primary thesis of our organizational analysis. We believe that there are a number of forces that will lead to sustained higher inflation. And among those forces, energy is a major contributing factor.

We believe, and really what we now observe, is that the world is shifting from an era that we've enjoyed for so long. A period during which where there has been global peace, cooperation, easy trade, abundant energy. Now things are shifting towards an era of geopolitical conflict, deliberate economic antagonism, energy scarcity, and so many other things that lead to a higher level of sustained inflation. Now, I always have to acknowledge, "Hey, we could be wrong. Of course, we could be wrong," and there are some factors, such as the possibility of Putin putting his tail between his legs. There may be some signs that Russia and USA/NATO are ready for peace in Ukraine. That may certainly happen, and I think if that does happen, there's probably going to be some at least short-term benefit in energy markets.

But peace in Ukraine won't solve the long-term fundamentals. It doesn't solve the long-term energy challenges. So that may happen, but even if it does, I don't think that actually gets us out of the woods here. Is there going to be a major shift in political control in the United States? Well, we answered that question a couple of days ago, and the answer seemingly is no. Will there be a sudden reversal of political ideology from the big guy? Absolutely not. In a recent press conference, he was asked by an Associated Press reporter "What will you do differently in the next two years of your administration based on the results of this election, what the people are telling you?" And his answer was, "Nothing. Nothing," because he believes, because they didn't completely get their asses kicked, that he has a moral mandate to continue doing exactly what he is doing.

I don't think we can count on a sudden policy shift, and everything's going to be so much easier in energy markets, and they're going to cozy up with the oil and gas companies now, et cetera. I don't think that's very likely. Possible, but unlikely. Has China put down its saber, completely abandoned zero-COVID policy? No, probably not. Just recently the CCP announced that they were going to loosen up the restrictions, so instead of keeping everybody locked down for 10 days, now it's going to be 8 days, and so when encountering things like this, you go, "All right. Maybe that's a little baby step in the right direction."

But it doesn't really move the needle in terms of opening up a global economy and creating more supply. When you lock down millions and millions and millions of people across an entire planet, including one of the most important manufacturing hubs (China), you're going to have a decrease in supply, And you don't get out of an inflation situation until you can fix the supply problem, so China's definitely a major factor in this. Will there be a major oil discovery? Could be, but given the sort of political and regulatory headwinds, it makes it a little bit unlikely they'd be able to exploit that. Are they going to suddenly change the minds and embrace uranium and nuclear power? Possibly, but doesn't really look like that is a realistic possibility at the moment, given what's happening at Cop27.

So there's all of these issues, where I fully acknowledge and conclude "Well, hey, we could be wrong about some of these things, and there may be some other things that we're not even thinking of, but we feel like we're on pretty safe ground in assessing an outlook that is more inflationary." By the way, an inflationary outlook coincides with literally 5000 years of human history. History is inflationary, period. And don't forget about social security. We have eight years before a massive multi-trillion dollar, probably 10 to 20 trillion bailout of social security will be required. Nobody wants to talk about it. Nobody acknowledges it. The only people that actually do are the people that write the Social Security annual trustee reports, including the Treasury Secretary of the United States.

Don't take my word for it. Just read the Social Security Annual Report of the Trustees, and they say in black and white (for anybody that actually cares to want to read this stuff) "We are going to run out of money in this year. Circle the date. Put it on your calendar," and it's probably going to be accelerated given that now having to pay the highest cost of living increases in the history of the program. So that's probably going to accelerate the date that the entire reserve and the trust funds are depleted. That's going to be a huge problem, and so they are probably going to say, "Well, tough luck everybody. We are going to have to cut your social security benefits". In the report, then essentially state "Oh. We can slash it, something like 30%, 40%, and we could slash everybody's benefits."

Even then, the Social Security program won't keep up for inflation, because they won't have the money to do that. So over time the benefits will be less and less and less, which is going to cause a major social crisis in the US, given how tens of millions of people are dependent on social security. To avoid this, the US Government has got to figure out a way to bail the program out. And they're just going to print fiat currency (or issue centralized digital currency) to do that, because they don't have the money. They just don't have the money. They don't have sufficient financial assets. The only few financial assets they have on the government balance sheet are student loans, and you've got the stooges there trying to get rid of it. They said, "No, no, no. We don't want this asset." Fortunately, they were actually blocked by a federal judge recently, so we'll see what happens with that, but this is a huge issue.

If we think about, over a longer period of time, literally over the next decade, and you factor in things like social security and the need to actually bail out this program, the argument for inflation feels like you're on even much more solid ground. I'm just going to go ahead and call it stagflation, because although everybody's talking about recession, it's up to the National Bureau of Economic Research to make the definitive call. Nobody else is entitled to an opinion. There's a bunch of experts that sit in a room and decide whether or not we're in a recession or not. Maybe we are already. Maybe we're not, but if we are, or we're heading that way and we're in inflation, that means stagflation. What works well in stagflation? Well, investing in real assets makes a lot of sense.

Energy makes a lot of sense. Agriculture makes a lot of sense. Mining makes a lot of sense. Productive technology, which is different than consumer technology. Consumer technology is the things that people just sort of swipe, scroll, and actually make us less productive, because you've got an entire generation of people staring at their phones all day, can't look up, swiping and scrolling, scrolling and swiping, like zombies, right? That makes us less productive. I'm talking about productive technology that makes things better, faster, swifter, cheaper, just overall propels our civilization forward. There's a lot of really interesting productive technology out there.

There are a lot of really great ways to invest in businesses that produce valuable goods and services, and this isn't uncharted territory. We've seen this before. We saw what happened in the 1970s. Real assets did very well. Energy companies. Oil companies did pretty well. Exxon stock (back when it wasn't combined with Exxon Mobil) did pretty well. Exxon, between dividends and cap gains, averaged about 12% a year during the 1970s. Precious metals did phenomenally well. Precious metals were up 20x and more. Agriculture, farmland did extremely well in the 1970s. So this is not something that we have to be clueless about. We can look to history and see the things that have worked in the past.

I want to leave you with a simple message in saying that this is not the end of the world. It is not the end of the world.

I actually just finished a book called 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Remember when I told you that the Mycenaean faded into history around 1180 B.C.? This was a real thing that happened. I am so fascinated by this period because of what it can help us to understand about the present, and it's really almost prehistoric because of very few records that exist. There are some records from the Egyptians. We owe a lot to the ancient Egyptians and the scribes that they had for their writing system. A lot of what we know actually comes from the Egyptians, and this is a really fascinating period of history. It's called the Bronze Age Collapse, because there was a cascading failure of all the major Bronze Age civilizations right around the same time. The author of this book (American archaeologist Eric H. Cline) picked 1177 B.C. as the year, but it really happened over a period of several decades.

But over a relatively short period of time, you had literally the collapse of multiple civilizations: the Hitite Empire, the Mycenaeans, the Minoans, the Trojans, the Babylonians, the Amira. There's so many different cultures, tribes, kingdoms, and civilizations that just ended. They just ended. They ceased to exist, and a lot of historians have studied this and tried to figure out why. In the record, both the historical record, as well as the archeological record, the Bronze Age collapse is often discussed as being due to a number of different causes. One was climate change. They point to climate change. There were volcanic eruptions that caused really significant declines in agricultural output, because they didn't have enough sunshine. Literally, not enough sunshine in order to produce their food.

And so there were multiple preconditions which favored mass starvation, famine, and so forth. And if that was not enough, these civilizations and their capital cities had a very powerful enemy. One of the most mysterious enemies in human history was a group that historians refer to as the sea peoples. Some historians claim this group might have just been refugees, possibly from Troy, that just started combing down through the Levant and the Mediterranean, destroying kingdom after kingdom. They were angry, and they were very powerful. There was also some evidence that there was a pandemic, and the pandemic could have wiped out a lot of people and a lot of civilizations. A collapse of trade is another explanation, that there may very well have been an issue with the tin trade, and tin, again, was the most important commodity at the time, like oil is today as discussed above.

We don't really know for sure exactly what triggered this cascade of collapsing empires, but we can look to history and see that there were a variety of forces that literally pushed all these civilizations out of existence. But the good news is, is it wasn't really the people so much that went into decline. It wasn't human civilization itself that went into decline. It was the systems of the time. It was the empires. It was the governments. It was the centralized authoritarian systems that were in place reinforcing the model that "We're going to have a king, and the king's going to make all the decisions. We're going to have this ruler, and the ruler's going to make all the decisions. We're going to have a pharaoh. We're going to have a whatever, and this person's going to make all the decisions." In retrospect, from an economic standpoint, that was just crazy.

It doesn't work, and that was the end of that period of civilization. That was that system that collapsed, a system based on giving all the power and all the authority to one person, to a single expert that gets to lord it over all the peasants and the commoners, and say, "I and I alone can tell you what to do. I and I alone can deliver us from this crisis." That's the system that collapsed. It wasn't like everybody just spontaneously combusted. The people were okay. It was the system itself that collapsed and, most notably, was replaced by a new system, because after this happened in 1177 B.C., over time a new system developed, a system we now call the classical Greek civilization. The rise of ancient Athens and the Athenian model of governance which we now call democracy, and which gave rise to the great philosophers Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, and Hippocrates.

All of the people that made a major impact on all future human civilization came out of the out the collapse of the old centralized autocratic system, from the Bronze Age collapse. This enabled the rise of democracy, a new system where public policy was not dependent on one person who gets to lord it over everybody else, in which everybody else got to participate in major political decisions. A new system that flourished, a new civilization that flourished, where intellectual property flourished, where the economies flourished, were trade flourished. In the end, everybody was better off because the old system collapsed, allowing replacement by a new system.

I absolutely think that is what we are in for, because there have been so many examples over the last few years that the system that we have right now is just not working. Our future story cannot continue to look exactly like the present.

Our future will take its own story arc. There will be all sorts of fantastic things that perhaps future storytellers will insert about what happened; monsters, beautiful women, whirlpools, and all sorts of things, but most likely we will emerge onto a much, much higher trajectory with a new system in place. One where, just like the ancient Greeks, we develop a new system of self-governance. The classical Greeks created a new system of delegation. They had a new system of trade. They had a new system of money. They had a new system of economy. Everything was new, and it worked, and they flourished, and so will we. That's why, when we see everything happening in the world, we look at energy, we look at climate, we look at politics, or whatever, it's okay. It's okay, because there's something better coming. We don't know exactly what it looks like, but it will absolutely be based on a true story.

Those are my remarks. As always, I appreciate your time, interest and attention.

I think the positive polyanna stuff is good but this is a stretch. The difference today is technology. Man has always trended toward corruption, that hasn't changed. BUT the fact they can create drones, phones, internal tracking devices, push jabs that kill and likely load you with nanotechnology and the like, I just have no idea how things are going to turn out fine. We're going to be able to get all this technology into the hands of good folks? That would be the only way and I have to laugh at even the thought of that. Good men do not do what needs to be done to get rid of bad men. It's like guns. Bad men will always have them. Good men follow rules and give them up. The good man on earth can't win.

Nice story. Maybe the shining new world will be awesome but it’s going to be built on the devastation of all of us right now. We are going to starve; go to war; have nothing to keep our freezers full of food going; no money so properties will be confiscated and people will die trying to do that; sickness from lack of food and energy. He doesn’t talk about all of what will happen, first, before his new world crawls out of the mess. That “first to happen” stuff would be us. I would like a different story for right now. A way to avoid the collapse part and the tyranny part. Just sayin’