Travels with Justine, Part 3

In Search of Chipoko... and scones... and finding poachers.

In Search of Chipoko … and scones … and finding poachers!

By Justine Isernhinke, Fellow and Head of Geopolitics and UAP Research, The Malone Institute

PART 3 of 3

<see this link for Part 1, and this link for Part 2)

Finding Poachers

Surprisingly, since we left Harare to travel to the mountains of the Eastern Highlands, the roads had been excellent. This lulled Nick and I into a false sense of security. Had we known what was in store, we might have had a change in plan. However, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, we headed out west to Bulawayo.

We crossed two-thirds of the entire country in seven hours and change. The terrain changed from mountainous to baobabs, then rocky outcrops and finally to flat open acacia scrub land.

As the terrain and vegetation changed, so too did the quality of roads and we soon were back to potholes once we entered the outskirts of the city of Bulawayo.

Chipoko, never far from our minds has a connection to Bulawayo. Bulawayo has one of the most historic UFO photos ever taken (imaged during December 1953):

29th December 1953: An Unidentified Flying Object in the sky over Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia. (Photo by Barney Wayne/Keystone/Getty Images)

In Bulawayo, we stayed with my friends, Janine and James, who run the best horse-riding safari in Hwange National Park. I’d be on their safari the year before and loved it. They had a lovely house where they kept their horses and dogs. James and I took the dogs for a walk and came across a large African snail which is hard to show on a photo but its about the size of an adult rat!

That night, whilst we ate a mean steak cooked by Nick, we asked them if they had seen any Chipoko and they said they had once. One night they noticed a strange square yellow light that moved oddly in the sky before vanishing. (Told you… everyone in Zim has seen something!)

At another sunrise, Herbie, our trusty 4x4, was packed with new provisions bought in Bulawayo. James saw us off and we drove up north to Hwange National Park. James warned us the roads were bad. “Bad” would imply they still existed. For the most part, they didn’t. It was like trying to drive across the surface of the moon in an area that was the worst hit by asteroids! It took us over 3.5 hours to crawl up that road, narrowly missing trucks that are equally determined to avoid the potholes.

Nick and I had planned to stay with a mutual friend, Nigel Kuhn. Nick and Nigel were friends from years ago as they partied their wasteful youths away in Harare. I was friends with Nigel through my passion for wildlife conservation.

When I launched myself into the conservation world ten years ago, I soon discovered that most non-profits were merely a ruse to have foreign well-meaning donors fund someone’s lifestyle in the bushveld. It took some time to learn to discern who was the real thing and who was merely a scrounge. Chengeta Wildlife was one non-profit that very quickly convinced me that they were the real McCoy. I met Nigel first in New York and then in London. I followed their work closely when they were in Mali training rangers to protect the desert elephants that roam the southern reaches of the Sahara Desert. The poachers were also the smugglers of drugs, arms, contraband and people. Real nasty characters, and Nigel fell back on his military training more than once.

Nigel met us down the Gwaai road which was a “quick" 45 min drive to Camp Silwane where I was staying. Nick, who had been going on and on about sleeping under the stars during various points on our trip when it looked like we might have to make a plan for the night, grabbed the opportunity to camp at Nigel’s place while I glamped at the Lodge.

Nigel took over the anti-poaching unit (APU) 4 months earlier and was running to catch up to his own high standards of how an AOU operates. Within a couple of weeks, he’d already had some HR challenges as the team was trying to adjust to a new sheriff in town and some were not willing to adjust. But Nigel, who is there working for CWF - Conservation Wildlife Fund - has an incredible vision for the areas under his protection.

Nigel showed us the snares collected by the APU team over the last 5 years. Snares can be made from almost anything but usually wire fences and barb wire will do. Africa is the great recycler. Anything that can be repurposed will be. Not always in a positive way. Each of these snares (and there are about 30,000) in the photo below, represents an animal that would have gotten caught and slowly died in anguish and distress as it tried to escape. Bush meat poaching is the most prevalent kind of poaching but attracts the least amount of international donor attention. There is nothing “glamorous” about collecting snares. It is tiring, hot work. A thankless job. Much of their work is. But each snare found is a life saved.

Our first afternoon proceeded at the bar/lounge area that looked out onto the plains. Nigel, a few drinks in, started talking about his ranger selection course coming up and what the rangers were expected to do. Nigel boasted that he would do everything that he asked them to do. This prompted 24 year old Wayne, the young manager of the camp, built like a rugby forward (i.e. shoulders as wide as he is tall), baited him to a push-up challenge! It was on. The two men dropped to the floor and belted out push-up after push up (“nipple to floor”, as Nigel insisted) until Wayne decimated Nigel. Wayne is a good bit younger than Nigel so it must have been youth and not fitness that won the day, right?

After a long raucous night around the camp fire, Nick drove back to the Lodge in the morning to pick me up so we could explore the surrounding areas. We headed into the bush and drove a fair distance, before it dawned me on that again the Zimbo-in-charge was lost. The Hondee Valley all over again (see Part 2). We backtracked and eventually made our way further inland. It had been raining so much that most game was deep in the bushveld far away from the water pans.

Unlike a zoo, where the animals have nowhere to go, wild animals go where the food and water is and that may be very far from the road you happen to be driving on. We saw vultures in huge numbers so we knew there was a kill nearby but the ground was soggy, and Herbie untested in such environments. We did find a few leopard tortoises which I love. Well, let’s be honest, the small stuff is the BEST. Give me a snake or monitor lizard sighting any day over a Kudu or Zebra.

We stopped by a picnic site and met an armed ranger there whose job it was to protect people from wild animals walking into the camp site. We invited him for a coffee and a few rusks. He told us he spends a month there at a time. Nick and I couldn’t comprehend how lonely it must be to guard this place in the middle of park with no electricity, just your hut and the odd traveler that would come past and maybe talk to you. For this job, he gets paid a pittance. His monthly salary is the equivalent of a family order from Starbucks. He had his own chipoko experience. Near his village, there was a bridge where a man had been struck and killed while riding his bike. Since then, glowing lights (orbs?) appeared to people at night when they crossed the bridge. “Chipoko” really does seem to cover every kind of paranormal experience.

The next day, Nick and Nigel made me breakfast by a stunning plan with palm trees and all. Probably the best bacon and egg sandwich I’ve eaten. (I highly recommend this restaurant. You can contact Nick for reservations.)

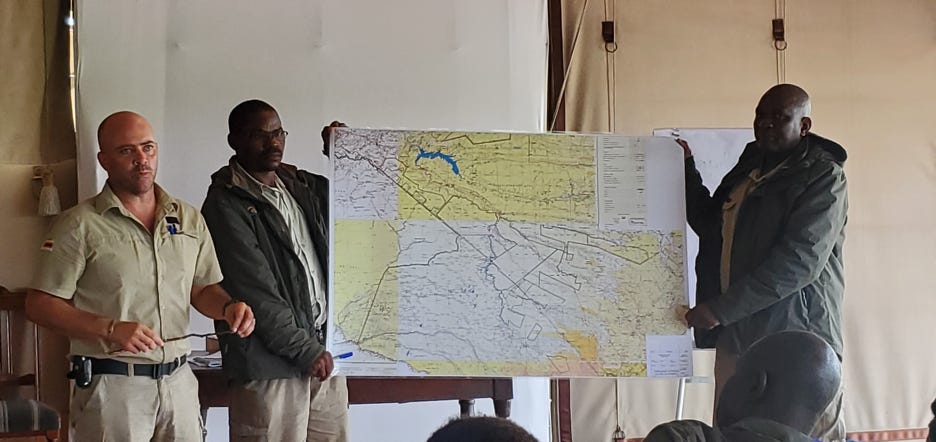

The following day, at the crack of dawn (everything happens at the crack of dawn here) Nigel took me to listen to his presentation given to another camp’s rangers about the grand plan of CWF to increase the terrain under their protection and re-introduce white rhino back into those areas. It essentially involves collaborating with the different owners of the concessions that run alongside the border of Hwange National Park and convince the owners to give up hunting and opt-into “photographic safaris” as they term it these days.

As we climbed back into the truck, Nigel noticed that there was water collecting at the bottom of one of his headlights. He made a mental note to get that fixed because the truck jolted too much on the dirt roads, that headlight lamp would blow out. Little were we to know how much that was to play a role later that day.

We left the camp and, without fail, another Zimbo gets lost… but we eventually found the way home. After lunch we headed over to a mutual connection of all of ours. Brent Stapelkamp is a local Zimbo who runs his own non-profit with this wife. He came unfairly into the crosshairs of the then-authorities when he was too vocal about Cecil the lion which was shot (by that dentist). Since that event, Brent has lived the quiet life. But he lives true to his word. Brent preaches living in harmony with the land. He and his wife built their own house from local materials and then build their own self-recycling toilet and a bathtub where you can sit and look at the stares while you soak. They work with the surrounding villagers to impart their knowledge about holistic ranching, building and working with their neighbors to spread better ways to work the land and create viable incomes. One of the interesting things I learnt from them is that they use vuvuzelas (see photo to the left, such instruments of auditory torture entered the world when South Africa hosted the Soccer World Cup) to chase away lions that come over from Hwange Park looking for territory away from the reigning prides in Hwange. They have found that if you creep up to a lion and blast a vuvuzela in his ear, he will run away in fright and very unlikely to return… the key is in scaring them that first time! Anyone keen to try?

On the way to Brent’s place, Nigel got a call that the forest rangers who look after an area under the Forestry’s authority and not CWF, had captured a poacher. The poacher had come in with hunting dogs to hunt down antelope and other animals for the bushmeat trade. The rangers had shot his dogs (standard procedure) and arrested him. Having no vehicle of their own, they needed Nigel to give them a lift to the police station where they could complete the arrest of the poacher.

When we arrived back to Nigel’s house, Nigel asked if I wanted to tag along for the ride to the police station. Knowing my passion for conservation and my screenplay on poaching, he thought it might be interesting. Plus he wanted the company… not that he said, but I’m sure of it.

Nigel explained that it would take us 2 hours to get to the rangers’ camp and then 1.5 hours to the police station. It would then take another 1.5 hours back to the rangers’ camp to return the rangers and then 2 hours back to base. I am on holiday, I shrug. When does one get to do stuff like this? I have a quick shower at Nigel’s, pack a peanut butter sandwich and some biscuits, borrow Nick’s rain jacket and off we go. It was 7pm by the time we left camp. We picked up one of the CWF rangers, Sibanda, who was supposed to guide us to the rangers’ camp in the Forestry area.

Right about then, it started to rain and when I say rain, I mean it pelted it down in something reminiscent of the great deluge that had Noah building an ark. In the dark and rain, Sibanda hunkered down in the bed of the truck and fell asleep. On dirt roads that all look the same, passing trees that all look like all other trees, and in the dark, we got lost. Not just lost, mind you, so lost that I thought we might never see home again. Everything looked the same to me. We saw our own tire tracks again and again. After some stern words with Sibanda, whose only job there was to tell us where to go, we eventually headed in the right direction. But by now, trees had fallen down with the heavy rain and we continually had to stop to move branches and trunks out of the road. We also lost that one headlight…and Nigel had to squint through the rain and the dismal light that the one surviving headlight gave.

At midnight - so 5 hours later - we arrived at the rangers’ camp and picked up 2 of the forestry rangers and one of CWF’s rangers as well as the poacher. The poacher had his hands cuffed in front of him. His face showed a mix of anger and despondency. What struck me was that he was incredibly skinny and barefoot. The reality of bushmeat poaching is that most of the poachers are looking to make a quick buck but they don’t have much else in the way of career-options. If there is one thing the rich West could do to stop poaching, is to build businesses in developing countries. Give people another way to earn an option. However, with the instability of governments and corruption, it’s not so easy to just “invest” in these places.

With the 5 men all tucked into the bed of the truck, we headed towards the exit of the Forestry area and towards Lupane police station. After about 30 mins of navigating downed trees and dirt roads, one of the rangers taps on the roof. We stop. The ranger asked if we can drive to the poacher’s house so he can get some medication. Nigel is in no position to argue so we change direction and head into an area that soon became filled with kraals. Kraals are homesteads where the locals fence off an area with branches and sticks to protect their livestock from predation from lions, leopards and the like.

At about 1.30am (well past the time I turn into a pumpkin) we stopped while the poacher, accompanied by the rangers, collected his medicine and a photocopy of his ID.

We continued on our way. Conversation in the canopy of the truck had died by now. Nigel and I had exhausted all of our love-stories and war-stories.

Suddenly, the truck launched into the air and bounced side-to-side and crashed into a tree. I hit my head several times on the roof of the truck (no one wears a seatbelt in a game vehicle over there) but luckily we were not going fast enough to collide with the windscreen. We clambered out. We had no idea what happened.

The five guys in the back of the truck were moaning. Sibanda was screaming. Nigel, his EMT and military training kicking in, quickly assessed Sibanda. He had hit his ribs as he was tossed around in the back.

All of the other guys were bruised but not injured. I was ok as far as I could tell. Nigel was good. Time to assess the truck.

Nigel turned the key. The truck’s engine worked fine.

One blown tire on the right side.

And the truck was wedged on bushes and branches of the small tree/large bush we smacked into.

First order of business was to move the truck off the tree. One of the rangers grabbed the axe and started hacking at the tree trunk. But a quick analysis showed that it wasn’t the trunk that was the issue but that the front axle was stuck on the low branches. I suspect that, but for those low branches absorbing most of the impact of the energy, we would have hit that tree trunk and the damage would have been far worse - to us and the truck.

We finally backed up the truck. As Nigel assessed the damage, I went to look for what caused it.

Engaging my internal Sherlock Holmes, I deduced that the right tire must have glanced off a tree stump on the edge of the road that was concealed by a small bush. And it was the right side of the truck where the headlight had gone out. In the dark, the one headlight probably lit the bush but not the brown tree stump behind it.

As an aside, we christened Nigel “Stumpie” after this event…

Where we had the accident in relation to Lupane (that’s about 15kms - about 9.5miles)

It was now 2am in the middle of the bush.

Nigel organized the men to get the spare tire off the side of the truck as he tried to get the blown tire off. One of the rangers had to operate a crank jack which requires some skill… I watched this poor ranger, who clearly had never seen a car jack in his life, never mind this kind of jack, pump furiously at it for 5 mins and the car not lift up an inch off the ground. Eventually, Nigel came over to see what was going on and had to do it himself. They are tricky jacks. I certainly couldn’t do it.

Whilst Nigel had to end up doing everything to change the tire, I held the flashlight and quality-controlled…. That is, until Nigel couldn’t get the old tire off the truck. Try as he might, that tire was stuck. We looked underneath the truck and something seemed to bashed in. The wheelbase had been bent slightly.

Nigel, I’m sure, reassessed his life decisions in a few seconds as to how he ended up here. For my part, I was happy it had stopped raining and was amazed that this scene was very similar to the one in my screenplay. Except I have hungry leopards in my story. Our greatest danger at this point of our journey were more likely feral dogs from the huts around us.

Falling back on his years in the UK’s Royal Green Jackets, Nigel decided that the first order of battle was that we needed to complete the mission. This meant taking the poacher to the Lupane police station. We packed up the car, leaving one armed ranger with the truck to keep it safe from human predators. As we started to walk, Sibanda cried out and crumpled. He couldn’t go anywhere. We had to leave him in the truck with the other ranger and said we would pick him up later and take him to the clinic. I didn’t have much food, but gave them what I had and gave them some milk I’d taken with me.

We started walking again. Ahead of us the two Forestry rangers walked holding their grumpy poacher still in handcuffs. Nigel and I walked together. By this juncture, the rechargeable flashlights had died. My takeaway from this is that NEVER take rechargeable anything. Bring something that uses batteries and bring lots of batteries.

I acquired a little bit of a military background in the UK while I lived there. I turned to Nigel and asked him with a huge grin on my face: “Nige, are we “tabbing”?” Tabbing is the term the British army uses to describe what Marines call “humping”… walking very long distances with a heavy backpack. I had my little backpack on. Nigel grunted “Yes”. My response was an even bigger grin… “Yeah, I’m tabbing!”

After about 30 mins, I felt a few drops of rain… moments later, the heavens opened up on us like something out of a bad Vietnam War movie. I was drenched by the time I managed to get my bright yellow poncho on.

There was no reprieve. Nothing to do but walk. After about an hour, we started to see some lights in the distance. At least we were heading in the right direction.

When my feet finally hit tarmac, all I wanted to do was kiss it. I was soaked to the bone and tired. Nigel was too grumpy to talk to. I basically spent the entire time talking to myself aloud about books I’d read on Survival… I think subconsciously I was trying to bring all the few bits of knowledge about survival to the fore of my mind in case it was needed.

As we walked down the road, we had trucks pass us by and I nearly got hit by one. I forgot that the roads are so badly potholed that the trucks swerve to avoid them and will just drive into the shoulder of the road at a moment’s notice.

We then hit “civilization” - a defunct gas station that marked the entrance to the main road to Lupane central. We passed by some shops and bongo-bongo music (my term for the bass that you hear miles away from non-identifiable music in the African bush). It was eerie.

We were walking in pitch darkness because everyone was conserving their mobile phone battery.

The rangers in front of us suddenly called out and shined their phone for a second. They had nearly stood on a puff-adder that was crossing the road. The puff-adder has a deadly reputation for the snake that strikes the most people - they don’t move until you’ve stood on them. They don’t even give a polite warning like a rattlesnake. But in the silent dark at 3.30am, the rangers had heard the snake hiss. That they could hear the hiss and knew what it was, is why they’re rangers. Real survival skills.

Of course, being a snake person, I had to get close to take a photo. I said to Nigel that it was the first time I’ve seen a puff-adder in the wild (if you can call Lupane the wild) and was super happy about that. Nigel just grunted. In fact most comms with him by now consisted of grunts and grumpy sounds.

We got to the police station - which was more like a house you’d find in Fallujah after a bombing raid. No glass in the windows, no door. Rather open air. As the rangers booked in the poacher, Nigel asked the policewoman to call a taxi for us. I did wonder at this, thinking that I doubt Uber runs anything out here… turns out I was right. No Uber. No taxis. 4.00am in the morning is when most upstanding inhabitants of Lupane are fast asleep.

Nigel joined me on the tiny wooden bench facing the open door. He says to me we need to wait till they can get ahold of a taxi which will take us back to Sibanda and the truck.

With the little bit of battery and reception I had on my phone, I had messaged Nick, our friend Greg back in Harare and the manager of the camp I was staying at. I also posted on Facebook that I was spending the night at the cops’ station in Lupane. I was thinking that, at the very least, the rescue mission to find us would have a clue where to begin!

Nigel and I snuggle up under my yellow poncho. As I folded my arms, I feel the biscuits I tucked away earlier. I pulled them out and offered them to Nigel. We ate a few but soon realize that dry biscuits without water isn’t the best idea. We tried to get some shut eye.

At 6.30am, the policewoman woke us up and said that a taxi driver was on his way over. A guy pulled up in a tiny Honda Fit. I climbed into the front seat. Nigel and the other two rangers squished into the back. For the first time all night, I was warm. God bless Japanese Honda Fit’s heating system and their cozy soft seats (2.5 hours on a hard bench is no fun). But now began a back-and-forth between the taxi driver and the rangers. The taxi driver then got on his phone. Nigel and I had no idea what was going on.

The taxi driver drove us up to the same t-junction with the desolate gas station that we walked past that early morning and proceeded to call every taxi driver in Lupane which seemed like a lot more than one would think. Apparently, with the intense rain, he was not prepared to drive his precious Fit down the drag (the muddy roads) to our truck. I still tried to contact Nick. In fact, normally Nick was known to be up at 5am most days but today, he was AWOL. Of all days/nights.

Eventually, after much more haranguing, the rangers found a guy with a Nissan double cab and canopied bed that was heading that way. He had other passengers with him and Nigel and I ended up in the back of the bed (I guess our turn) whilst we trundled slowly down a muddy track trying to get back to the truck.

There was an argument between the rangers. We ended up taking one way that one of the rangers insisted upon which got us badly stuck in mud. It took some time to reverse out. By the time we got back going the other way, Nick and Nigel made contact by phone - it was now 8am.

With that sorted, and Nick on his way to us in our trusty Herbie, the taxi guys stopped and refused to go further. The road ahead of us had turned into a muddy quagmire. They would not go further. Certainly, their 4x4 of a Nissan truck did not have the tires for mud like this. Nigel and the two rangers hopped out of the car. Nigel arranged with the taxi driver to wait with me at the gas station. The taxi was supposed to wait for Nigel to walk back to the truck and pick up Sibanda and meet then Nigel at the same spot they dropped him off at.

Nigel and the rangers headed out onto the muddy road by foot.

The taxi drivers took me back to the gas station and we waited 2 hours for Nick to make his way to us. The roads had turned into rivers and Nick told me when he arrived that he didn’t think he was going to make it to me several times.

Nick’s video of driving on the Gwaai river… I mean road:

I gave Nick a massive hug. I was so happy to see him.

I bought the taxi driver and his friend a drink and Nick and I got some gas, smokes for Nick and headed back down the Gwaai road to the camp. Another 2 hours for Nick.

When we got back to camp, Nick fueled up a coffee, some biscuits and a cigarette. With that, he took off again to meet with Nigel in Lupane. I lent him some cash as Nigel had no money on him and they needed money for the clinic and gas for Herbie. It was now 12 noon. I took the best hot shower in the world and crawled into bed and slept.

Meanwhile, Nick braved the wet Gwaai road and the potholes back to the humming hustle-and-bustle of Lupane. I’m not sure of how they managed to meet up. But Nigel ended up walking 2 hours to get back to the truck. His initial plan was to build a makeshift stretcher and carry Sibanda out.

But somewhere along the way, he hired a man with a donkey cart and they donkeyed Sibanda all the way from the truck to the clinic. It turns out that this was the better decision because the rain continued and the roads turned to rivers. There was no way they were going to get any vehicle back down that way.

Nick and Nigel came back to camp at 10pm that night. Nick had driven between 6-9 hours that day. Both them arrived at my camp broken and battered. We had a quick meal and everyone went to bed.

It took Nigel about 10 days to be able to get his truck towed out of there. Luckily the damage wasn’t as bad as we thought, but we could never have succeeded in changing a tire that night.

Sibanda didn’t break his ribs as we all feared. Just badly bruised. It still must have hurt a ton.

Photo above: Following Nigel out of Hwange on the Gwaai road the day we left. The water had subsided substantially by then.

The next day, Nick and I packed up and headed back to Harare. Stumpie and I are forever trauma-bonded.

We drove to Harare via Bulawayo because for some reason no one has thought of creating a drivable road between Harare and Hwange. It took us over a day to get back to Greg’s. Along the way, we met with a Facebook friend and her famous husband The Major. He was in the Rhodesian War and when the war ended, he joined the new Zimbabwean Central Intelligence Office (CIO) where we undertook some suspect intelligence operations. He was quite entertaining to talk to… until both my friend and Nick stepped out to go for a smoke and some shopping.

Alone with The Major, his tone changed and he leaned in and whispered to me: “I know who you are.” Now, something about me: I’m cocky at the best of times. So I leaned back in my chair, folded my arms and slowly said: “So who am I?”… which in hindsight (and bearing in mind that we’re all geniuses in hindsight) was not the best way to handle The Major or his question.

Because there and then proceeded something like an interrogation where The Major clearly wanted me to admit something, but I honestly had no idea what, so I just became cheekier by the minute. Frustrated with my attitude, he gave in and said: “You’re an intelligence officer”.

At which moment, I burst out laughing which really set him off… again, in hindsight, I shouldn’t have had this reaction.

The Major then proceeded to accuse me of running an intelligence operation in Zimbabwe. I tried to keep a straight face. He was serious. Simultaneously, I thought it was both the funniest thing I’d heard and was kind of flattered that I was clearly so good as to be mistaken for an intelligence operative.

Luckily, the tension dissipated when Nick and my friend returned. We soon parted ways. I couldn’t wait to tell Nick. To this day, we chuckle over it.

For the record, no, I don’t work for any intelligence agency. Though, if “they” are reading this, I am willing to be honey-trapped by a 6’6” Jason Momoa look-alike that owns horses. (Just in case, you know.)

Back in Harare, we had a couple of days to unwind where we met up with Tayanna from the first episode of this travelogue and talked about the Ariel School.

On Sunday, I flew back to South Africa and thus ended my adventure in Zimbabwe!

Thank You, for writing such magnificent memoirs. I am so enjoying your adventures!

WOW, what a fantastic adventure and life you live to the fullest; congratulations on your survival!