Universal Repeated mRNA Boosting Was (and is) Bad Policy

Making sense of mRNA COVID vax IgG4 class switching and public health policies

Universal Repeated mRNA Boosting Was (and is) Bad Policy

Robert W. Malone, MD, MS. Vice Chairperson, CDC/ACIP and designated ACIP member, COVID vaccine working group

The opinions expressed below are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the US Government, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or the ACIP COVID vaccine working group.

Executive Summary

Universal, repeated COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccination was a predictable policy failure rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding, or dismissal, of immune biology. In addition to ignoring the known severe adverse events of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, including cardiac damage and death, regulatory decisions relied on crude antibody titers and unvalidated surrogate assays while ignoring antibody quality, subclass distribution, cellular immunity, durability, and timing. When protection against infection waned rapidly after the primary series, the reflexive response was frequent re-boosting, despite no prospective evidence supporting the number of doses or the interval. The immunologic consequence, now well documented, is progressive immune modulation: sustained IL-10 signaling and IgG4 class switching. IgG4 preserves antigen binding and neutralization but actively limits inflammation and Fc-mediated effector functions. This biology explains the observed paradox of continued protection against severe disease in high-risk patients alongside failure to prevent infection and transmission, and aligns with evidence that SARS-CoV-2 evolution has been driven primarily by neutralization escape rather than escape from inflammatory elimination.

COVID-19 is fundamentally an inflammatory disease, and immune dampening can be lifesaving in high-risk populations. However, applying the same tolerance-leaning strategy to children and healthy young adults, groups at minimal risk of severe disease but central to viral spread, offers little benefit and undermines stated public-health goals. Repeated boosting before immune resolution predictably stacks signals, reinforcing tolerance rather than antiviral clearance, increases cumulative risk of severe adverse events, and may have broader implications for responses to other vaccines, infections, and immune surveillance.

The central conclusion is not that mRNA vaccines “failed,” but that policy goals were misaligned with the immune biology these products produced. A single, blanket strategy was imposed on heterogeneous populations with divergent risks. The data now demand a course correction: a targeted vaccination policy grounded in respect for individual patient differences and bioethical fundamentals, prioritizing immune response quality over quantity; an explicit distinction between preventing severe disease and preventing transmission; experimentally determined booster intervals; and risk-stratified shared decision-making rather than universal, repeated boosting.

Introduction and Background

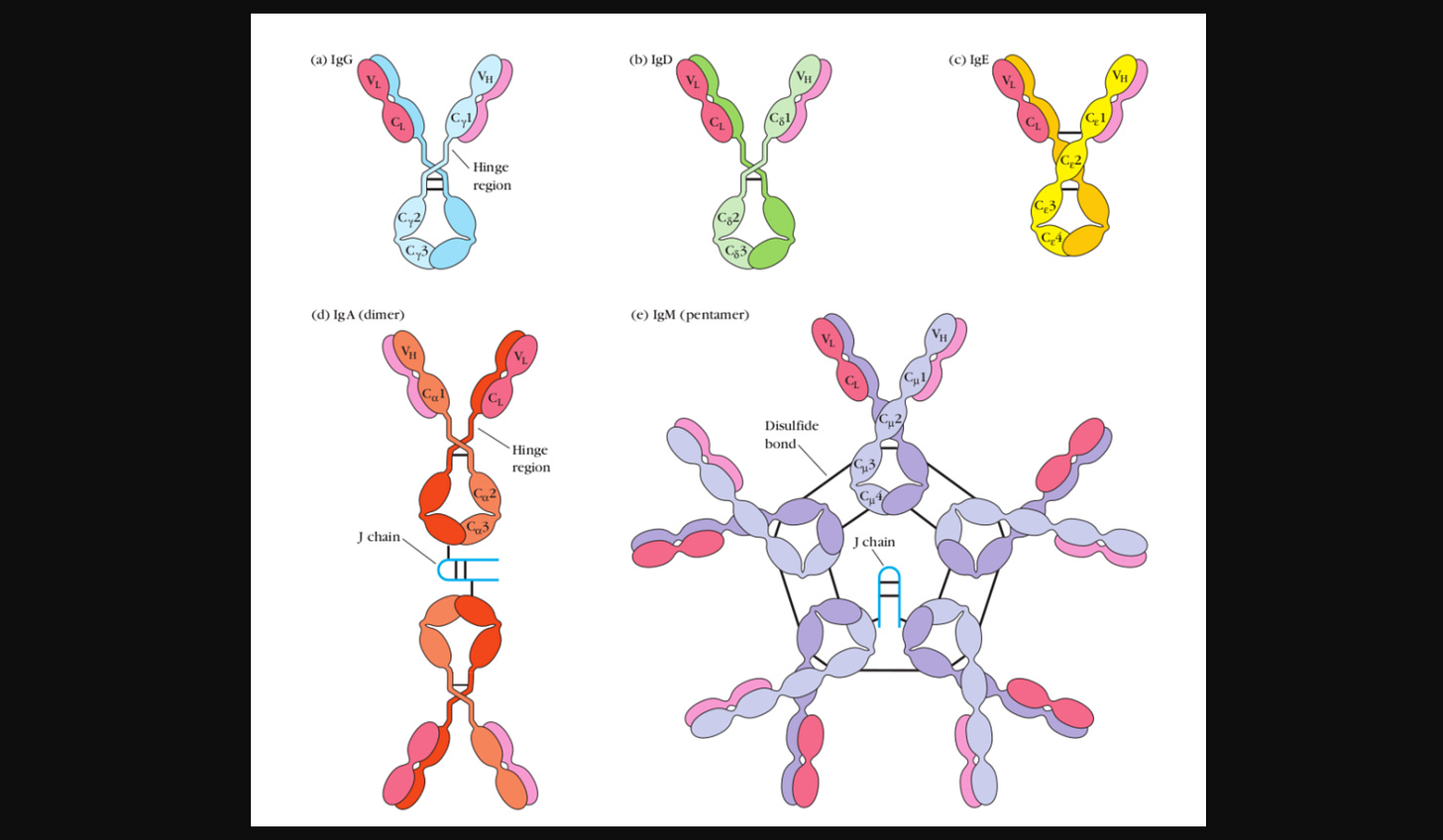

Antibody (immunoglobulin) responses are surprisingly complex. This is particularly true in the case of antibody “maturation” and immunoglobulin (Ig) class switching. Immunoglobulin class switching is the way your immune system changes the type of antibody it makes without changing what the antibody recognizes. The repeated boosting strategy for COVID-19 mRNA vaccines drives patient immune responses down an immunosuppressive rather than inflammatory pathway. This has implications for other vaccines, infectious diseases, and cancers that may affect the overall health of people who receive frequent COVID-19 mRNA vaccine boosters.

Keeping this simple for the moment: At first, when your body encounters something new (like a virus or allergen), it produces a basic antibody (IgM) that allows it to react quickly. Over time, as the immune system “learns” more about the threat, it can “switch” to different antibody classes (IgG, IgA, IgD) that are better suited for the situation. Some of these are good at causing strong inflammation to clear infections, while others are better at quietly blocking or controlling things that aren’t dangerous. This switching allows the immune system to fine-tune its response, deciding whether to fight aggressively or respond more calmly based on experience (and time post-infection). There are various subclasses (and even sub-subclasses) of the basic antibody categories that the immune system can switch to; for example, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 are known subclasses of immunoglobulin G (IgG). Each one has unique biological and immunologic properties and functions.

FDA, CBER, COVID mRNA vaccines, denialism, and desperation

Unfortunately, the simplistic “titer” and “neutralizing antibody” logic of the FDA and COVID mRNA vax manufacturers on display during the COVID-crisis mostly served to illustrate the ignorance (or lack of honesty) of the “experts” who have been driving (and enforcing) grossly uninformed and naive public policy decisions about COVID mRNA vaccinations.

You may recall that, under former CBER director Dr. Peter Marks (neither an immunologist, virologist, nor a vaccinologist), the FDA asserted that the ability of COVID mRNA “booster” products to provide protection could be measured using surrogates of total antibody responses (titers) achieved in mice, or “neutralizing” antibody titers produced in mice as measured using unproven assays that had not been demonstrated (“validated”) to predict protection in humans.

As an aside, in an amazing display of either ignorance or denialism, both Dr. Marks and U Penn Vaccinologist Dr. Paul Offit also asserted that the cationic lipid delivery formulations used to deliver the synthetic mRNA into the cytoplasm of human tissue cells could not also deliver the (bacterially methylated) DNA fragment contaminants (adulterants) produced by the mRNA manufacturing process into patient’s cells. In fact, cationic lipid formulations are the globally preferred method for non-viral delivery of DNA sequences and fragments into cells.

In a non-emergency setting, neither of these measures of antibody responses would be sufficient to make regulatory policy or authorization decisions about a human vaccine product. They would barely merit a peer-reviewed publication in a third-tier journal. But under CBER Director Dr. Marks’ oversight, these nuances were disregarded in a rush to provide a solution to the problem of rapidly waning protection from infection, spread, and disease (poor durability) observed after the primary series of two mRNA vaccine doses that had been so actively promoted by the USG and, in many cases, mandated. The solution promoted by the FDA, the CDC, and the USG was to provide frequent additional boosts after the first two doses. This policy was implemented universally without doing the hard work to determine whether repeated boosting was a good idea, let alone when the boosters should be administered.

Small point of clarification - standard vaccine industry jargon is that the first dose is for “priming”, and the second dose is considered a “booster”. This language reflects the fundamentals of immunology and immune responses. So these were actually additional “boosters”.

The problem was (and is) that after two doses of an mRNA COVID vaccine (prime and boost), protection against infection develops slowly, peaks briefly, and then declines rapidly. So, what did the FDA, CDC, manufacturers, leading academic vaccine advisors, and the US Government decide to do? They advised prompt re-administration of another (“booster”) dose of the same mRNA product when measured antibody titers were declining; this was the reflexive answer. Completely ignoring the importance of (difficult to measure) cellular immunity in viral infection control.

As I said back then, give a three-year-old a hammer, and everything becomes a nail.

COVID mRNA vax rapidly waning effectiveness

Here is a short summary of the situation. There is little to no protection (against infection, spread, disease, or death) for the first 10 days after the first mRNA dose, mild benefit by about two weeks, and peak protection only after the second dose, reaching a maximum around one to two weeks later. At that point, short‑term effectiveness against infection (at peak protective response) as measured in initial randomized clinical trials can reach about 85–95% (relative, not absolute risk reduction), though it is now known that the measured risk reduction varies by viral variant.

For comparison, absolute risk reduction measured in the initial Pfizer randomized trial was approximately 0.84%. The differences between these two measurements (relative vs absolute risk reduction) and the rationale for why absolute risk reduction is the preferred statistical measure for communicating efficacy or effectiveness are summarized in the FDA publication “Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User's Guide”. Under the direction of Dr. Marks and as communicated by NIAID Director Dr. Fauci, all USG public communications referred exclusively to relative risk reduction value rather than the FDA-preferred absolute risk reduction.

The rub is that, around two to three months after the second shot, already modest absolute COVID mRNA vaccine-induced protection against infection and spread of SARS-CoV-2 begins to wane further, dropping significantly by four to six months. By six months, neutralizing antibody levels are often close to baseline, and infection becomes common again, though protection against hospitalization and death remains higher for longer. Remember that last point - it is important in the context of IgG4 class switching. In some studies, measured vaccine effectiveness drops below zero, indicating “negative effectiveness” (an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection), although only a small subset of studies have reported negative effectiveness.

In other words, protection against infection provided by the initial two-dose series peaks roughly one month after the second dose, but fades sharply within half a year, while protection against severe illness persists somewhat longer. The characterization of the duration of protection (against infection or disease) is collectively referred to as “vaccine durability”. From these facts and descriptions, it is easy to infer that the sample timing of immune response and protection endpoints (infection, sickness, or death) afforded by a COVID mRNA vaccine is a critical variable for any scientific study seeking to analyze or compare efficacy, effectiveness, benefits, or risks associated with these products.

When Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine (Comirnaty) and Moderna’s vaccine (Spikevax) received full FDA licensure (BLA), the approved indication language stated, in substance:

“for active immunization to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2”

The FDA licensed COVID-19 mRNA vaccines to prevent COVID-19 disease, not to stop infection or spread, and not to reduce disease severity.

The drop in efficacy or effectiveness durability was a mystery back then. The prolonged persistence of the pseudouridine-modified mRNA and associated modified (two proline aa) spike protein antigen was not known at the time, as the FDA did not require (previously required) rigorous pharmacokinetic (including pharmacodistribution) analyses of the active drug product. Also not disclosed was the contamination/adulteration of the doses administered to the general population by short, bacterially methylated DNA fragments. Now we know better. Once again, hold that thought.

Do COVID mRNA vaccines provide protection against severe morbidity and mortality in high-risk patients?

Peer-reviewed studies and public health surveillance indicate that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines protect against severe disease, hospitalization, and death, even when protection against infection wanes over time. Examples of analyses supporting this conclusion include the following:

Prevention of hospitalization and disease severity:

A large observational study found that mRNA vaccines were associated with high effectiveness (~85%) in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among immunocompetent adults, and vaccinated individuals were much less likely to progress to death or invasive mechanical ventilation compared with unvaccinated peers.Influenza and Other Viruses in the Acutely Ill (IVY) Network. Association Between mRNA Vaccination and COVID-19 Hospitalization and Disease Severity. JAMA. 2021 Nov 23;326(20):2043-2054. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.19499

Prevention of death and respiratory failure:

CDC data covering March 2021–January 2022 showed that two or three mRNA doses reduced the risk of COVID-19–associated invasive mechanical ventilation or in-hospital death by ~90%, with even higher protection (~94%) during Omicron when three doses were received.Effectiveness of mRNA Vaccination in Preventing COVID-19–Associated Invasive Mechanical Ventilation and Death — United States, March 2021–January 2022. MMWR (CDC) Weekly / March 25, 2022 / 71(12);459–465

Protection in the Omicron era:

A target trial emulation study during the Omicron period reported that booster doses lowered the risk of COVID-19–related death by ~79% and also reduced hospitalizations, illustrating substantial protection against the most severe outcomes even with variant circulation.Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine Boosters Against Infection, Hospitalization, and Death: A Target Trial Emulation in the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant Era. Ann Intern Med. 2022 Dec;175(12):1693-1706. doi: 10.7326/M22-1856. Epub 2022 Oct 11.

Meta-analysis and high-risk populations:

Meta-analysis across millions of adults with underlying conditions found that mRNA vaccination significantly reduced the risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and death, with stronger relative benefits in higher-risk subgroups.Comparative Effectiveness of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccines Among Adults with Underlying Medical Conditions: Systematic Literature Review and Pairwise Meta-Analysis Using GRADE. Adv Ther. 2025 May;42(5):2040-2077. doi: 10.1007/s12325-025-03117-7. Epub 2025 Mar 10.

The studies indicate that COVID mRNA vaccines provide significant protection against severe COVID-19 complications and death across variants and population groups, even as protection against infection decreases over time. While effectiveness is not durable and can wane within months after vaccination, the vaccines’ protection against severe outcomes in high-risk patients has been documented in peer-reviewed literature and CDC public health surveillance studies.

Here comes the (additional) repeated boosters

In response to documented poor durability of these mRNA COVID products in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in light of previous USG-promoted assurances of long-term protection from infection, spread, and disease after accepting both doses, the FDA, manufacturers and their “experts” decided to recommend a third (booster) dose of mRNA, despite the absence of clinical data to support repeated dosing levels or timing.

After the original two-dose primary series of Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccines, the FDA authorized a single booster dose approximately 6 months after the primary series to help restore waning immunity for most adults. An EUA supplement specifically supported the use of a booster about six months after completing the primary series in eligible individuals aged 16 and older. Over time, the FDA, and subsequently CDC/ACIP, expanded booster eligibility to include younger age groups and immunocompromised persons, and recommended additional booster doses (secondary booster, dose #4 and beyond) for older adults (e.g., ≥50 years) and certain immunocompromised individuals, generally with at least a 4-month interval after the previous booster.

Booster timing was not systematically studied in prospective clinical trials; rather, it was based on applied “expert opinion”. In this way, the FDA and CDC shifted US policy to an unprecedentedly frequent dosing schedule for a highly experimental genetic vaccine about which little was known. This schedule was unsupported by any substantial human studies, and instead appeared to be based on a mixture of willful ignorance, disregard for regulatory norms, wishful thinking, and reactive desperation arising from the observed poor durability of protection.

IgG4 class switching and tolerance.

The unintended consequences of what may have been willful ignorance of these facts have yielded the curious case of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine-driven IgG4 class switching, which has now been documented in many peer-reviewed publications investigating the immunological consequences of repeated boosting as previously recommended by the FDA and CDC.

Examples include:

Post-vaccination IgG4 and IgG2 class switch associates with increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections. J Infect. 2025 Apr;90(4):106473.

Class switch toward IgG2 and IgG4 is more pronounced in BNT162b2 compared to mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccinees. Int J Infect Dis. 2025 Oct;159:107990.

Repeated COVID-19 mRNA vaccination results in IgG4 class switching and decreased NK cell activation by S1-specific antibodies in older adults. Immun Ageing. 2024 Sep 14;21(1):63.

Class switch towards spike protein-specific IgG4 antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination depends on prior infection history. Sci Rep 13, 13166 (2023).

Delayed Induction of Noninflammatory SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Specific IgG4 Antibodies Detected 1 Year After BNT162b2 Vaccination in Children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 43(12):p 1200-1203, December 2024.

For the sake of completeness, currently (2025–26), the FDA and CDC have moved toward variant-updated vaccines with guidance that focuses on risk-based, individualized decisions about additional doses rather than a blanket booster schedule for all ages. However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the states that have chosen to follow AAP rather than FDA/CDC guidance are still recommending mandatory frequent COVID-19 mRNA vaccine boosting for children and adults.

To a first approximation, “IgG4 class switching” is best interpreted as a biomarker of antigen-specific immune regulation and tolerance, arising from repeated exposure in a low-inflammatory context. It reflects qualitative modulation of immune responses rather than impaired immunity or increased disease risk.

What is important about IgG4 (in this context) is that it confers immunologic tolerance-related properties (in contrast to other IgG subtypes). IgG4 is considered tolerogenic because it preserves antigen recognition while actively limiting immune activation and inflammation.

Structurally and functionally, IgG4 binds antigens effectively but engages activating Fcγ receptors on immune cells very weakly, and does not activate the classical complement pathway, thereby preventing amplification of inflammatory responses. In addition, IgG4 antibodies can undergo Fab-arm exchange, reducing their ability to cross-link antigens or form large immune complexes that would otherwise trigger immune cell activation. Fab-arm exchange is a process in which one heavy-light chain pair swaps with another IgG4 molecule. As a result, many IgG4 antibodies in circulation become functionally monovalent: each arm may recognize a different antigen, preserving neutralizing activity while preventing effective cross-linking of the same target. This loss of functional bivalency is another key reason IgG4 is weakly inflammatory and contributes to its tolerogenic properties.

Finally, IgG4 also competes with more inflammatory antibodies, such as IgG1 and IgE, thereby acting as a “blocking antibody” that suppresses allergic and inflammatory reactions. Together, these features enable IgG4 to support immune tolerance by recognizing antigens (such as the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein) without provoking tissue-damaging inflammatory responses or activating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (killing of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells).

IgG4 class switching is driven by regulatory immune environments rich in IL-10 and regulatory T cell activity, meaning that IgG4 both reflects and reinforces anti-inflammatory immune regulation. To better understand “IgG4 class switching” driven by repeated boosting, consider allergen tolerance induction, the process by which repeated, controlled exposure to an allergen (i.e., repeated boosting) retrains the immune system to respond without triggering one type of harmful inflammation (mast cell activation). Mechanistically, allergen immunotherapy shifts immune responses by class-switching away from IgE-mediated mast cell activation toward a regulatory profile characterized by driving increased IL-10–producing regulatory T cells and IgG4 “blocking” antibodies. These IgG4 antibodies compete with IgE for allergen binding while minimizing inflammatory effector functions, resulting in reduced allergic symptoms despite continued exposure. In this case, IgG4 class switching is therapeutic for those suffering from various toxic (potentially life-threatening) allergic responses. However, IgG4 class switching can also direct a predominant antibody response away from a more productive, protective anti-viral profile toward one biased toward tolerance to a pathogen.

Immune tolerance becomes clinically problematic when immune regulation (such as IgG4 class switching) suppresses protective immune functions needed to control viral replication or disease, rather than simply preventing unnecessary or harmful inflammation. In other words, tolerance is helpful when it reduces cell and tissue damage, but harmful when it allows a real threat to persist or worsen. Immune tolerance becomes clinically problematic when immunological regulatory mechanisms suppress protective immune functions required for pathogen control, tumor surveillance, or disease resolution.

Antigen-specific tolerance that preserves protection against severe outcomes is generally considered adaptive rather than pathological, and this may be the case with IgG4 class switching in COVID mRNA vaccination. However, if the objective of the treatment (vaccination) is to reduce or prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection or spread, providing a modestly prolonged reduction in disease risk (by frequent boosting) consequent to driving IgG4 class switching, for what is often a mild disease, in exchange for failure to protect against infection and spread is not a compelling public health argument.

Booster timing, stacking, and IgG4 class switching

Booster timing matters because it determines whether immune signals resolve or stack (accumulate), and IgG4 class switching is most likely when boosting occurs before full inflammatory and germinal-center resolution.

When boosters are closely spaced, residual antigen expression, ongoing germinal center activity, and unresolved innate signaling overlap with the next dose. This creates signal stacking: repeated exposure to the same antigen in a relatively low-inflammatory context.

Under these conditions, regulatory feedback pathways (notably IL-10, regulatory dendritic cells, and Tregs) become progressively stronger, and B cells are more likely to class-switch toward IgG4 rather than inflammatory subclasses like IgG1 or IgG3. In other words, the immune system interprets the antigen as persistent but non-dangerous and adapts by dampening effector inflammation while preserving binding and neutralization.

In contrast, longer booster intervals can allow antigen clearance, contraction of germinal centers, normalization of innate signaling, and resolution of regulatory cytokines before re-exposure. For long-lived pseudouridine-modified mRNA vaccines, antigen clearance may take many months; therefore, booster intervals should be determined experimentally if the goal is to reduce stacking.

When a booster is given after this reset, the immune system is more likely to re-engage inflammatory pathways and reinforce IgG1/IgG3 responses, reducing the likelihood of IgG4 dominance. This is why IgG4 class switching is generally not observed after primary vaccination or widely spaced boosts, but becomes more apparent after multiple, relatively frequent mRNA booster doses.

In short, frequent boosting favors immune modulation and IgG4, while spaced boosting favors inflammatory recall and classical antiviral antibody profiles. IgG4 class switching reflects timing-dependent immune adaptation to repeated antigen exposure, not loss of immunity or safety, but it does have implications for how booster schedules shape protection against infection versus severe disease.

COVID-19 as an Inflammatory Disease

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 in which host inflammatory responses play a central role in determining disease severity and clinical outcomes. While viral replication initiates infection (and spread), substantial evidence demonstrates that dysregulated or excessive inflammation is a primary driver of the clinical course of tissue damage, organ dysfunction, and mortality in moderate to severe disease.

Clinical severity correlates more strongly with markers of systemic inflammation than with viral burden beyond the early phase of infection. Complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, thromboinflammatory events, endothelial injury, and multisystem inflammatory syndromes are predominantly mediated by immune and inflammatory pathways rather than direct viral cytopathic effects.

Effective prevention and management of COVID-19 requires both antiviral and immunomodulatory strategies, applied at appropriate stages of disease. Antiviral interventions are most beneficial early in infection, while anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating therapies improve outcomes in later stages when inflammatory processes predominate. Bluntly, it is not the infection and replication that get you; it is a hyperactive secondary inflammatory response to that infection and to persistent SARS-CoV-2 antigens that drive COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.

In general, vaccines that reduce the risk of severe disease, hospitalization, and death act by modulating immune responses toward controlled, protective immunity rather than unchecked inflammation. Reductions in infection or transmission, while desirable, are not the sole determinants of public-health benefit. Whether by intention or circumstance, the current mRNA vaccine boosting strategy is heavily biased toward preventing COVID-19 disease morbidity and mortality, and against preventing infection and spread. Instead of a “one size fits all” policy, there should be different policies for different cohorts with varying susceptibility to severe COVID-19 disease.

For example, the healthy pediatric and young adult population is at exceptionally low risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19, but is a major contributor to overall circulating viral burden (infectious pressure) in the general population. For this population, reduction in viral replication and spread should be the primary consideration.

In other (much smaller) cohorts at higher risk for severe COVID-19 disease (elderly, obese, etc.,) a reduction in morbidity and mortality is more desirable. In most cases, a key characteristic of these higher-risk cohorts is their elevated inflammatory set points, which predispose them to a more pronounced inflammatory response during the (second) disease phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to otherwise healthy patients.

The inflammatory set point refers to the baseline level and responsiveness of an individual’s immune system toward inflammation, reflecting how readily and how strongly inflammatory pathways are activated and resolved in response to stimuli. It influences susceptibility to inflammatory disease, severity of infection, and the balance between protective immunity and immunopathology.

Implications for SARS-CoV-2 evolution and population-level persistence

Viral evolution is overwhelmingly driven by how much and how often the virus spreads, so a vaccination strategy biased toward reducing disease severity rather than viral replication and spread may contribute to the evolution of mutations that evade vaccine-induced antiviral immunity. In theory, the dominance of IgG4 antibodies could alter immune selection pressures by maintaining neutralizing activity while reducing Fc-mediated clearance, thereby permitting infection without severe disease and favoring viral variants that evade neutralization rather than inflammatory elimination. This type of selective pressure is not unique to IgG4 and also arises under common conditions such as IgA-dominated mucosal immunity, waning antibody levels, partial immunity from prior infection, and vaccines that primarily protect against severe disease.

There is strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 evolution has been driven primarily by selection for neutralization escape rather than escape from inflammatory elimination, and this pattern is well documented across variants. See, for example:

Wilks SH, Moller R, Andersen KG, et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution on a dynamic immune landscape. Nature. 2025;published online. This study integrates deep mutational scanning, antibody neutralization data, and genomic surveillance to show that SARS-CoV-2 variants continually acquire mutations in the spike protein that reduce susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies induced by prior infection or vaccination, and that these immune escape dynamics match historical variant prevalence and fitness trends in the population.

Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Zhang F, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. eLife. 2020;9:e61312. This laboratory study showed that spike protein mutations conferring resistance to commonly elicited neutralizing antibodies can be readily selected in vitro and that such variants are present in circulating virus populations, supporting neutralization escape as a key evolutionary driver.

SARS-CoV-2 evolution shows strong evidence of selection for escape from neutralizing antibodies, with mutations concentrated in spike protein epitopes (the specific vaccine antigen), while targets of inflammatory and T-cell–mediated immunity remain largely conserved. This pattern indicates that viral fitness is driven by evasion of neutralization to sustain transmission in partially immune populations (such as those with a predominantly IL-10/Treg/IgG4 immune response), rather than by escape from inflammatory immune elimination or increased pathogenicity.

Regulatory immune mechanisms, including anti-inflammatory cytokine signaling, IgG4 class switching, and immune resolution pathways, are essential components of recovery and protection against severe disease. Immune tolerance and modulation are therefore protective features of effective immune responses in the context of COVID-19 disease, but may be counterproductive for reducing infection and spread. Understanding this resolves the paradox in post-COVID-19 mRNA vaccine clinical data, particularly regarding repeated boosting.

From a public health policy perspective, COVID-19 should be understood as a disease for which the primary function of recent or current vaccination policy (eg. American Academy of Pediatrics and States following AAP recommendations) has been to prevent severe inflammatory outcomes in high-risk individuals while tolerating viral replication and spread in the general population including children and adolescents at very low risk for severe COVID disease.

Going forward, public health policies should be modified to simultaneously reflect the need to reduce replication and spread of SARS-CoV-2 in cohorts at low risk for severe morbidity and mortality, while prioritizing endpoints related to severe disease, hospitalization, long-term morbidity, and mortality in other cohorts at high risk for severe COVID-19 disease. “Natural infection” elicits a response that is more focused on inhibiting infection and spread, whereas the boosted mRNA COVID vaccines are better suited to suppressing harmful, later-stage inflammatory effects.

Impact of chronic high blood levels of IL-10 on vaccine responses, viral infections, and cancer risk

mRNA COVID-19 vaccines elicit dynamic immune responses that include transient elevations in IL-10 shortly after dosing and, upon repeated boosting, sustained IL-10 induction with associated regulatory antibody pattern changes (IgG4 class switching). For example:

IL-10 and other cytokines (IL-1β, etc.) significantly increased after the first Pfizer-BioNTech dose in healthy participants.

Transient increases in IL-10 are observed within days following the third mRNA vaccine dose.

Time-course analysis of antibody and cytokine response after the third SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose. Vaccine X. 2024 Sep 24;20:100565.

Appearance of tolerance-induction and non-inflammatory SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after COVID-19 booster vaccinations. Front Immunol. 2023 Dec 20;14:1309997

Chronic helminth (worm) infections, through sustained IL-10–mediated immune regulation, can attenuate vaccine immunogenicity and modify responses to unrelated infections. These effects reflect chronic immune recalibration toward reduced inflammation rather than immune deficiency, with outcomes that vary by pathogen, vaccine platform, and inflammatory dependence of protection.

Helminth-driven elevations in IL-10 can meaningfully influence both vaccine responses and susceptibility to other infectious diseases by shifting the immune system toward a more regulatory, anti-inflammatory state. The resulting IL-10–rich environment can dampen antigen presentation, reduce pro-inflammatory T-cell responses, and lower vaccine immunogenicity, particularly for vaccines that rely on strong inflammatory or Th1 signaling, while in some cases reducing immune-mediated pathology during infection. Consequently, immune and protective responses observed in clinical trials conducted in regions with chronic worm infections will differ from those obtained in regions without human worm infestations.

It is well known and documented that chronic high serum levels of IL-10 shift both vaccine and infection responses towards an anti-inflammatory (permissive of viral replication and spread) profile. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that repeated boosting with IL-10-promoting COVID mRNA vaccines will likewise shift immune responses to other vaccines and infections towards an anti-inflammatory profile. A form of secondary COVID mRNA vaccine-induced non-specific tolerance, or immune response shifting. This is an unanticipated and unaccounted-for consequence of current “one size fits all” frequent mRNA vaccine-boosting public health policies.

Sustained IL-10 signaling can contribute to cancer risk primarily by suppressing anti-tumor immune surveillance, especially when elevation is chronic and systemic. Chronic elevation of IL-10 has been associated with increased risk of malignancy in certain contexts, because sustained IL-10 signaling can suppress anti-tumor immune surveillance by inhibiting antigen presentation, cytotoxic T-cell and NK-cell activity, and promoting regulatory T-cell expansion. However, this relationship is highly context-dependent: IL-10 also plays a protective role by limiting chronic inflammation, which can itself drive carcinogenesis. As a result, transient or localized IL-10 responses are generally protective, whereas prolonged, systemic IL-10 elevation, often seen in chronic infections, parasitic disease, or within tumor microenvironments, may contribute to cancer progression. The balance between these effects depends on the duration, location, and underlying inflammatory context of IL-10 signaling, rather than IL-10 levels alone.

Key mechanisms driving IL-10 cancer risk include:

Inhibition of dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation

Suppression of Th1 and cytotoxic CD8⁺ T-cell responses

Expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs)

Reduced NK cell cytotoxic activity

Together, these effects can allow premalignant or malignant cells to evade immune detection, increasing the risk of tumor establishment or progression. Clinical and epidemiologic associations have been reported in:

Certain lymphomas (e.g., EBV-associated lymphomas)

Several solid tumors show an association between elevated IL-10 levels and poorer immune infiltration or impaired anti-tumor immunity, typically reflecting an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Well-described examples include:

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): High intratumoral or serum IL-10 correlates with reduced CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration, increased regulatory T cells, and poorer prognosis. IL-10 is linked to impaired antigen presentation in the liver’s already tolerogenic environment.

Gastric cancer: Elevated IL-10 expression is associated with decreased cytotoxic T-cell activity and increased Treg infiltration, particularly in infection-associated tumors (e.g., Helicobacter pylori–related disease).

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC): IL-10 contributes to a profoundly immunosuppressive microenvironment characterized by poor effector T-cell infiltration and dominance of regulatory immune cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Higher IL-10 levels have been linked to reduced dendritic cell function, lower CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration, and weaker anti-tumor immune responses, particularly in advanced disease.

Ovarian carcinoma: Increased IL-10 in ascites and tumor tissue correlates with higher Treg frequency, suppressed cytotoxic responses, and worse clinical outcomes.

Colorectal cancer (subset-dependent): In some non–inflammation-driven colorectal cancers, high IL-10 expression is associated with immune exclusion and reduced effector T-cell infiltration, though this contrasts with colitis-associated colorectal cancer, where IL-10 can be protective.

In these settings, systemically elevated IL-10 levels reflect or contribute to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

Is there a difference in class switching between “natural infection” and mRNA vaccines?

Both natural infection and vaccination begin with similar IgG1/IgG3 responses, but repeated mRNA boosting uniquely drives a shift toward IgG4, a feature not observed in SARS-CoV-2 infection alone (“natural infection”). This distinction highlights qualitative differences in humoral immunity driven by vaccine antigen delivery and dosing regimen.

After natural infection:

SARS-CoV-2 infection predominantly induces IgG1 and IgG3 antibody subclasses against the spike protein, with little to no detectable IgG4 in convalescent individuals. IgG2 is also uncommon in natural infection responses.

In natural infection, IgG4 levels remain very low or undetectable, indicating a traditional antiviral inflammatory response dominated by IgG1/IgG3.

Humoral immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine administration in seropositive and seronegative individuals. BMC Med. 2021 Jul 26;19(1):169.

Summary: Natural infection is associated mainly with IgG1 and IgG3, little IgG4, consistent with a classical antiviral response.

After repeated mRNA vaccination:

Primary SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination (first two doses) elicits strong IgG1 and IgG3 responses initially (similar to infection), but with continued boosting, there is a pronounced class switch toward IgG4 that becomes detectable months after the second dose and increases substantially after a third booster.

Repeated mRNA vaccine boosts show a progressive increase in spike-specific IgG4, from nearly absent to a significant proportion of the total IgG response several months post-boost. This shift reflects prolonged antigen exposure and germinal center maturation after repeated vaccinations, rather than an innate feature of viral infection.

Class switch toward noninflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol. 2023 Jan 27;8(79)

Summary: Repeated mRNA vaccination is associated with initial IgG1/IgG3 response, but this shifts toward significant IgG4 after multiple doses, reflecting an altered subclass distribution associated with repeated antigen exposure and potential modulation of effector function profiles.

In other words, both natural infection and vaccination begin with similar IgG1/IgG3 responses, but repeated mRNA boosting uniquely drives a shift toward IgG4, a feature not observed in SARS-CoV-2 infection alone. This distinction highlights the qualitative differences in humoral immunity driven by vaccine antigen delivery and dosing regimen.

Is there a difference in class switching responses between DNA and pseudouridine-modified mRNA vaccines? If so, why?

IgG4 class switching has been consistently observed after repeated mRNA vaccination and is thought to reflect platform-specific immune modulation driven by modified RNA, prolonged antigen exposure, and regulatory cytokine signaling, including IL-10. In contrast, DNA vaccines typically elicit more inflammatory, Th1-biased immune responses dominated by IgG1 and IgG3, and IgG4 class switching has not been a prominent or reproducible feature of DNA vaccine platforms.

As discussed above, evidence to date indicates that repeated dosing with mRNA vaccines can be associated with progressive IgG4 class switching after multiple booster doses, alongside a cytokine environment that includes IL-10 and other regulatory signals. These responses occur in the context of strong, sustained germinal center activity driven by robust antigen expression, while acute innate inflammatory signaling is moderated by nucleoside-modified RNA (e.g., pseudouridine) and by contaminating DNA fragments carried over from the mRNA manufacturing process. Innate sensing and signaling involve foreign RNA sensors, including TLR7/8 and RIG-I/MDA5, but pseudouridine chemical modification of the mRNA attenuates excessive early inflammation. With repeated dosing, this profile can lead to “signal stacking,” in which cumulative exposure favors immune modulation and antibody maturation over repeated inflammatory amplification. Additionally, pseudouridine modification of synthetic mRNA is associated with a prolonged mRNA half-life and expression of the encoded antigen (e.g., spike protein), further exacerbating the risk of immune stacking.

In addition to foreign RNA TLR7/8 and RIG-I/MDA5 signaling, the contaminating DNA fragments present in mRNA vaccines may also trigger sustained cGAS–STING activation. As discussed above, clinical data demonstrate that IL-10 production is activated and elevated serum IL-10 is observed after repeated mRNA boosting. IL-10 elevation is a key component of the immunoregulatory feedback that follows sustained cGAS–STING activation. This may reflect the development of a non-physiologic positive IL-10 feedback loop.

While acute STING signaling promotes inflammatory and antiviral immunity, prolonged activation induces IL-10–dependent pathways that suppress excessive inflammation and promote immune tolerance. Therefore, cGAS–STING signaling, while classically associated with antiviral and pro-inflammatory immunity, can also lead to immunosuppression when activation is sustained, repeated, or dysregulated. Acute STING activation triggers type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines that promote immune defense, but prolonged signaling induces counter-regulatory mechanisms that limit tissue damage. These include upregulation of IL-10, induction of regulatory dendritic cells and macrophages, expansion of regulatory T cells, and functional exhaustion or apoptosis of effector (helper and cytotoxic) T cells.

In addition, chronic STING signaling can suppress antigen presentation and dampen cytotoxic lymphocyte activity, shifting the immune environment toward tolerance rather than amplification. Thus, cGAS–STING functions as a double-edged pathway: protective during short-term activation, but immunosuppressive when signaling is persistent or excessive, contributing to immune regulation, tolerance, or impaired immune surveillance depending on context.

From a risk–benefit perspective, repeated boosting with pseudouridine-modified mRNA vaccines has been associated with increased IL-10 induction, expansion of regulatory antigen-presenting cells and regulatory T cells, and the emergence of IgG4 class switching in patients. The benefits of this pattern include reduced reactogenicity, preserved neutralizing antibody activity, and continued strong protection against severe disease. The theoretical risk is a potential reduction in Fc-mediated effector functions relevant to preventing infection, though not to protection against severe disease outcomes. Current FDA regulatory assessment interprets IgG4 induction as evidence of immune modulation under repeated antigen exposure, not as a loss of protection or a safety concern.

By contrast, DNA vaccines are generally associated with immune responses that are more strongly skewed toward a Th1 phenotype, characterized in humans by a higher relative induction of IgG1 and IgG3 antibodies and a greater emphasis on cellular immunity. These responses depend more heavily on inflammatory signaling pathways and cytotoxic T-cell activation, and there is limited or inconsistent evidence that DNA vaccines induce IgG4 dominance, even after repeated dosing.

Innate immune sensing of DNA vaccines is driven primarily through cytosolic DNA pathways (not TLR7/8 and RIG-I/MDA5 signaling), most notably the cGAS–STING axis, which in this context leads to acute, interferon-dominant signaling. Compared with mRNA platforms, DNA vaccines typically result in lower, shorter-term antigen expression levels and have historically been administered less frequently. Acute STING activation promotes robust type I interferon responses, with limited evidence for sustained IL-10 induction, creating an immune environment in which IgG4 class switching is uncommon.

From a risk–benefit perspective, the principal advantage of DNA vaccines lies in their strong Th1 bias and their ability to induce durable cellular immune responses. The main trade-off is a potentially higher reactogenicity profile due to more pronounced inflammatory signaling. Regulatory assessment, therefore, reflects minimal tolerogenic skew, with IgG4 not considered a prominent or defining feature of DNA vaccine responses. Overall, DNA vaccines maintain a higher inflammatory set point that does not favor IgG4 class switching, and to date, there is no robust literature demonstrating a reproducible IgG4 skew comparable to that observed with repeated mRNA vaccination.

The role of pseudouridine mRNA modification in IL-10 production and IgG4 class switching

Pseudouridine (Ψ) or N¹-methyl-pseudouridine (m¹Ψ) (and related synthetic nucleoside) modification of synthetic mRNA can plausibly influence IL-10 production and, indirectly, IgG4 class switching, although the effect is context-dependent and emerges mainly with repeated exposure rather than with single doses.

Pseudouridine (and related nucleoside) modification of synthetic mRNA alters innate immune sensing by attenuating excessive activation of RNA sensors such as TLR7/8 and RIG-I, thereby reducing acute inflammatory and type I interferon responses while enhancing mRNA stability and antigen expression. This modification does not directly induce IL-10 production or IgG4 class switching; rather, it creates an immune environment in which regulatory responses can emerge over time, particularly with repeated dosing. Prolonged antigen presentation and reduced inflammatory “danger” signals support sustained germinal center activity and adaptive immune resolution, during which IL-10 may be upregulated as part of normal feedback control. In this context, IgG4 class switching can occur in some individuals after multiple booster doses, reflecting immune adaptation and antibody maturation rather than immunosuppression or loss of protection.

Unmodified RNA strongly activates innate immune sensors such as TLR7/8, RIG-I, and MDA5, driving robust type I interferon and inflammatory cytokine release. In contrast, pseudouridine (Ψ) or N¹-methyl-pseudouridine (m¹Ψ) (or related synthetic analog) modification:

Reduces acute innate inflammatory signaling

Attenuates excessive type I IFN responses

Improves mRNA stability and translation efficiency

Allows higher and more sustained antigen expression

This design choice was made deliberately to improve tolerability and protein expression, not to induce immune suppression. While pseudouridine-modified mRNA does not directly “program” IL-10 production, it shifts the balance of innate signaling in a way that favors counter-regulatory responses over repeated exposures:

Reduced acute inflammation lowers strong Th1 skewing

Prolonged antigen presentation supports germinal center persistence

Repeated stimulation promotes regulatory feedback loops

IL-10 emerges as part of immune resolution, especially after boosting

Thus, IL-10 induction is secondary and adaptive, not a primary effect of pseudouridine itself.

In contrast to pseudouridine-modified mRNA, unmodified RNA strongly activates innate immune sensors, including TLR7/8, RIG-I, and MDA5, leading to robust production of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines shortly after administration.

This intense innate signaling limits mRNA stability and protein translation, resulting in shorter antigen expression and higher reactogenicity. The resulting inflammatory milieu favors Th1-biased responses and rapid effector immunity rather than prolonged germinal center activity or regulatory feedback. As a result, unmodified RNA is less likely to support sustained IL-10 induction or IgG4 class switching, even with repeated exposure, because strong inflammatory signals dominate over immune resolution pathways. Overall, unmodified RNA drives a more acutely inflammatory immune profile (analogous to “natural infection”), whereas pseudouridine-modified mRNA enables innate activation, extended antigen presentation, and, under repeated dosing, a greater tendency toward immune modulation rather than persistent inflammatory amplification.

In the context of the current COVID mRNA vaccines, potential immunosuppressive effects of pseudouridine (Ψ) or N¹-methyl-pseudouridine (m¹Ψ) modification of synthetic mRNA must be examined in light of the contamination (adulteration) of these products with the DNA fragments produced and carried through into the final drug product during the manufacturing process. The DNA fragments are DAM and DCM-methylated, and the RNA is hypermethylated by incorporation of N¹-methyl-pseudouridine. This will result in the presence of dual-methylated RNA:DNA hybrids in the final drug product that are biologically unique to these mRNA vaccine systems, a scenario with potentially profound implications. The combination represents a molecular pattern that literally doesn’t exist in nature and could create unprecedented immunological effects.

mRNA vaccine immune responses may be influenced by the combination of hypermethylated RNA (via N¹-methyl-pseudouridine) and residual methylated DNA fragments in the drug product. Pseudouridine modification dampens acute innate inflammatory signaling while prolonging antigen expression, favoring strong antibody maturation and immune resolution rather than repeated inflammation. Residual DNA fragments can activate the cGAS–STING pathway; while acute activation promotes antiviral immunity, sustained or repeated signaling can induce regulatory pathways such as IL-10 and T-cell regulation.

Together, these signals may account for aspects of the observed shift in immune response, especially with repeated dosing, toward immune modulation rather than inflammatory amplification, preserving neutralizing antibodies and protection against severe disease while potentially reducing inflammatory effector functions relevant to preventing infection and spread. This may also help explain observed patterns such as reduced reactogenicity, durable protection from severe outcomes, and IgG4 class switching in some repeatedly vaccinated individuals.

Summary and Conclusion

Immune responses to COVID-19, and to repeated mRNA vaccination, are far more nuanced than government-promoted public messaging has suggested. Antibodies are not just about how much is made, but what kind is made and under what conditions. Over time, and especially with repeated exposure, the immune system naturally shifts from aggressive inflammation toward regulation and tolerance. This process is normal biology, not failure.

Evidence now shows that repeated COVID-19 mRNA booster dosing can push the immune system toward a more regulatory state, marked by increased IL-10 signaling and a shift toward IgG4 antibodies. IgG4 antibodies still recognize the virus but are designed to limit inflammation rather than aggressively eliminate infected cells. This pattern resembles immune tolerance seen in allergen therapy and other settings of repeated, low-danger antigen exposure. It helps explain why boosters may continue to protect well against severe disease and death in high-risk patients, even as initial protection against infection and transmission is lost.

COVID-19 itself is best understood as an inflammatory disease: severe outcomes are driven less by viral replication and more by dysregulated immune responses. From that perspective, immune modulation that reduces inflammation is protective for high-risk individuals. However, if the stated goal of vaccination policy is to prevent infection and spread, especially in low-risk populations, then repeatedly reinforcing a tolerance-leaning immune profile may be counterproductive.

These findings highlight a key policy tension: a single vaccination strategy has been applied to very different populations with very different risk profiles. What may benefit older or high-risk individuals (by reducing inflammatory damage and mortality) may offer little advantage, and even potential downsides, for children and healthy young adults, where preventing transmission and avoidance of vaccination-associated risks should matter more than dampening inflammation.

In short, the scientific facts and findings summarized above demonstrate that repeated mRNA boosting primarily shifts immunity toward controlling disease severity rather than stopping infection. Multiple mechanistic pathways contribute to this effect, including some that have not been well studied. These pathways are not independent and may be synergistic, thereby creating a positive immune regulatory feedback loop. This is not necessarily dangerous, but it does challenge earlier assumptions, regulatory decisions based on limited immune metrics, and “one-size-fits-all” public health policies.

These findings also underscore the merit of a COVID mRNA vaccination policy based on shared decision-making, eg, careful consideration of the risks and benefits of vaccination and repeated boosting for each individual patient. A risk-based, individualized decision about additional doses rather than a blanket booster schedule for all ages, as currently advocated by the American Academy of Pediatrics and various states that follow AAP rather than Federal CDC guidance.

In terms of lessons learned for overall public health policy, future vaccine strategies would benefit from clearer goals, prospective, well-controlled clinical trials, improved immune measurements, and risk-stratified recommendations that align immune response biology with public health objectives.

Additional supporting references

Immunoglobulin Class Switching & Subclass Biology

Liu J.C. et al. Immunoglobulin class-switch recombination: Mechanism, regulation, and related diseases. MedComm. 2024;5(8):e662. — Review of the molecular mechanisms and regulation of antibody class switch recombination (IgM → IgG/A/E) including roles of AID and switch regions.

Chen Koneczny I. et al. IgG4 Autoantibodies in Organ-Specific Autoimmunopathies: Reviewing Class Switching, Antibody-Producing Cells, and Specific Immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2022;13:834342. — Overview of IgG4 biology, class switch regulation, and its immunologic implications.

IL-10, Regulatory Cytokines & IgG4 Induction

IL-10 indirectly downregulates IL-4-induced IgE production by human B cells and directly enhances IL-4-induced IgG4 production by B cells. ImmunoHorizons. 2018;2(11):398–410. IL-10 can enhance IL-4-induced IgG4 production by B cells under immune regulatory conditions, illustrating a key cytokine influence on class switching relevant to tolerance.

Mechanisms of immune tolerance to allergens: role of IL-10 and Tregs.

Akdis CA, Akdis M. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(11):4678–4680. IL-10 from regulatory T cells suppresses pro-inflammatory responses and plays a major role in inducing IgG4 while downregulating IgE, a signature of immune tolerance contexts (e.g., allergen immunotherapy).T regulatory-1 cells induce IgG4 production by B cells: role of IL-10.

van Boxel GI, et al. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):4718–4727. This study shows that IL-10-producing T cell clones increase IgG4 secretion from human B cells in vitro, supporting IL-10’s role in directing class-switching toward a regulatory isotype.

COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines & Antibody Subclass Dynamics

Irrgang et al. (2023) Class switch toward noninflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. — Shows significant induction of spike-specific IgG4 months after repeated mRNA vaccine doses; IgG4 levels were minimal early but increased over time and with boosting.

Immunity & Ageing (2024) Repeated COVID-19 mRNA vaccination results in IgG4 class switching and decreased NK cell activation by S1-specific antibodies in older adults. — Demonstrates class switch to IgG4 with repeated boosting and an association with reduced effector (NK) activation.

Post-vaccination IgG4 association study (2025) Post-vaccination IgG4 and IgG2 class switch associates with increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections. — Suggests that elevated IgG4 post-mRNA boost correlates with altered antibody functionality and may relate to increased breakthrough infections in a cohort.

Lasrado N, Collier AY, Miller J, Hachmann NP, Liu J, Anand T, et al. Waning immunity and IgG4 responses following bivalent mRNA boosting. Science Advances. 2024;10(8):eadj9945. This study found that after bivalent mRNA booster vaccination, neutralizing antibody titers against certain SARS-CoV-2 variants waned rapidly and that serum antibody responses were primarily composed of IgG2 and IgG4 with relatively poor Fc functional activity.

Vaccine Durability, Effectiveness & Boosting

Scientific Reports (2024) Antibody longevity and waning following COVID-19 vaccination in a 1-year longitudinal cohort in Bangladesh. — Documents waning of antibody responses after primary series and highlights why boosters were introduced, underscoring durability issues.

Clinical Infectious Diseases (2025) Effectiveness of the 2023-2024 Formulation of the COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccine. — Reports real-world effectiveness of contemporary mRNA vaccine formulations against infection, including declining protection over time.

Note on Neutralizing Antibody Dynamics

Infectious Diseases and Therapy (2026) IgG4 neutralization and sustained total IgG Fc-effector functions after repeated mRNA vaccination. — Although IgG4 rises with boosting, overall Fc functions and neutralization persisted, illustrating complexity of subclass effects.

General Immunology & Class Switching Basics

Stavnezer J, Schrader CE. IgH chain class switch recombination: mechanism and regulation. J Immunol. 2014 Dec 1;193(11):5370–5378. This foundational article reviews the molecular biology of immunoglobulin heavy-chain class switch recombination (CSR), including how activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) initiates CSR, the roles of switch regions and DNA repair pathways, and the genomic recombination that enables B cells to switch from IgM/IgD to other isotypes such as IgG, IgA, or IgE.

van de Veen W, Stanic B, Yaman G, Wawrzyniak M, Söllner S, Akdis M, et al. IgG4 production is confined to human IL-10-producing regulatory B cells that suppress antigen-specific immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Apr;131(4):1204–1212. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.014. This study demonstrates that IL-10–producing human regulatory B cells (BR1 cells) both suppress antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and selectively produce IgG4, providing evidence that IL-10 and regulatory B cells are directly linked to IgG4 class switching in the context of immune tolerance.

I am an accountant, not a physician or a scientist, and therefore cannot even begin to understand the complex science the brilliant Dr. Malone outlines in this post.

As an accountant, however, I do understand one thing: BIG PHARMA AND THEIR CAPTURED GOVT BUDDIES PROFITED IMMENSELY FROM PEDDLING AND MANDATING THESE POTENTIALLY HARMFUL REPEATED "BOOSTERS".

“children and healthy young adults, groups at minimal risk of severe disease but central to viral spread” I am convinced that this fear of children as vector was at the heart of many policy mistakes, including the closing of schools.