Homesteading: Revolutionary Foundations and the Culpeper Minute Men

A story about Virginian leadership, bravery and the birth of a nation

Few people remember the central role that mainstream men and women of the Commonwealth of Virginia played in creating the United States. We all hear of those involved in crafting the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, but most are unaware of those who stood alongside them and did the heavy lifting of pushing the British Empire out of the founding colonies. Frankly, I certainly had no real awareness of the role of the residents of this region in the Revolutionary War until Jill and I moved to the modest town of Madison, in Madison County, VA, and began homesteading our old, played-out hay fields. Our town and county take their name from President James Madison, whose tobacco farm (Montpelier) is just a stone’s throw from our little horse farm. Right over the hill behind our farm, you will find Hebron Valley Church, the oldest Lutheran church in North America. To the south of us is Charlottesville and Monticello, the historic home and farm of Thomas Jefferson. And just up the road towards Washington, DC, is the historic town of Culpeper, Virginia.

Fewer still know that the first President of the United States, George Washington, was trained and worked as a surveyor before his military commission and public service. At age 16 (around 1748), he began working as a surveyor under the guidance of his family’s friend, James Genn, and later joined professional surveying parties in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. He received formal training through self-study and on-the-job experience, including copying surveying manuals and practicing with instruments like the theodolite and chain. By 1749, at age 17, he was appointed as the official surveyor for Culpeper County, Virginia, a paid position that marked the start of his professional career. George Washington’s first job was laying out the town of Culpeper, VA. He conducted hundreds of surveys over the next few years, earning significant income and gaining expertise in land measurement, which later informed his military and presidential roles (e.g., mapping terrain during the Revolutionary War).

The Culpeper Minute Men

Culpeper, Virginia is not just another cute historic location. The town and its citizens played a pivotal role in the early days of the Revolution. The Culpeper Minute Men were important early Virginia volunteers, and were among the first Southern units to adopt the “minuteman” model, following the example of the original minutemen from Massachusetts who were formed and engaged a few months earlier. These were elite militia volunteers trained to be ready “at a minute’s notice” — hence “minute men” — to respond to British military movements. There is a direct historical and conceptual relationship between the Revolutionary War minutemen and the “well regulated Militia” clause in the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The minutemen were the living embodiment of what the Founders meant by a “well regulated Militia” — not a chaotic mob, but citizen-soldiers who trained, followed orders, and were ready to defend liberty.

“The advantage of being armed... the existence of subordinate governments, to which the people are attached, and by which the militia officers are appointed, forms a barrier against tyranny.”

James Madison (Federalist No. 46)

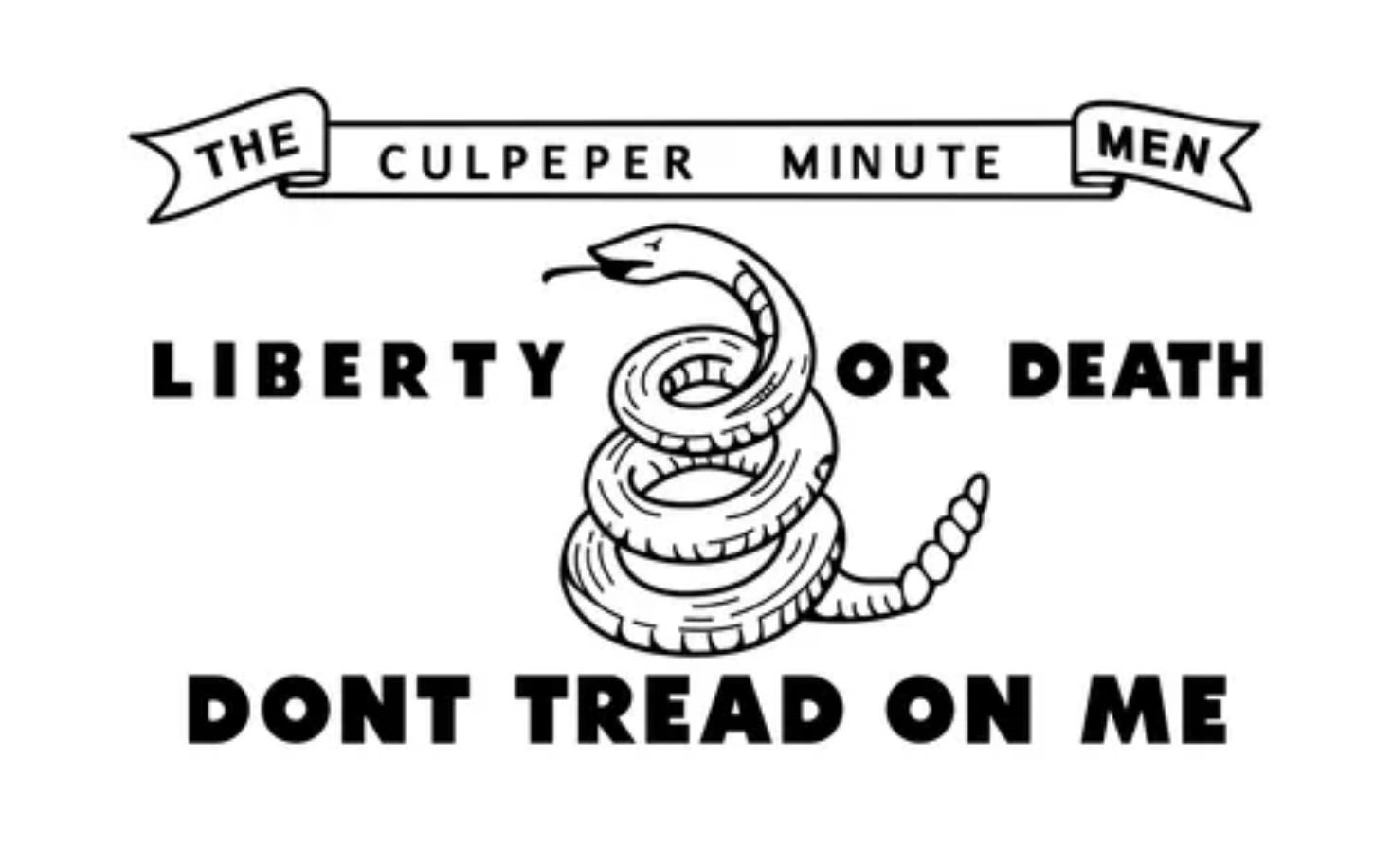

On July 17, 1775, in response to Governor Patrick Henry’s call for the Virginia militia to protect the capital at Williamsburg, the Culpeper Minute Men were officially organized under the Virginia Committee of Safety. Their uniform consisted of hunting shirts bearing the words “Liberty or Death” and a distinctive rattlesnake flag stating both “Liberty or Death” and “Don’t Tread On Me.” Leadership originally included Captain Philip Clayton, and the unit was later associated with figures like Patrick Henry and George Washington. Their distinctive banner with a rattlesnake, “Liberty or Death,” and “Don’t Tread on Me” is iconic. They joined the Continental Army in late 1775, served under Washington in the New York campaign (1776), and fought at Brandywine and Germantown.

John Christiansen, the executive director of the Museum of Culpeper History, reminds all “that flag, and the message it conveyed, really ensured the place of the minute men in popular memory.” “That phrasing would be revived over and over for the next 250 years. It was in the minds of the men who joined the reborn Culpeper Minute Men during the Civil War in what they considered to be another American Revolution. And the sons and grandsons of those Civil War veterans carried on that legacy into what would eventually become Culpeper’s National Guard company.”

Christiansen explains that newspaper articles from the 1880s and into the early 20th century describe current members of the unit as all “direct descendants” of the original minute men. A short history and description of the flag – one of the first used by the patriot cause – is almost always included.

The following historical narrative is derived in part from or informed by the WikiTree web page titled “Culpeper Minutemen Battalion 1775”.

In August of 1775 the House of Burgess met for its 3rd Virginia Convention to create 16 military districts and to appointed Patrick Henry as Commander of the 1st Regiment. The Culpeper District was created from Orange (Greene and Madison), Culpeper (Rappahannock) and Fauquier.

At the Virginia convention held May 1775, in Richmond, the Colony of Virginia was divided into 16 districts and each district instructed to raise and discipline a battalion of men “to march at a minute’s notice.”

Culpeper, Fauquier and Orange counties, forming one district, raised a cadre of 350 men, 150 men from Culpeper, 100 from Orange and 100 from Fauquier, called the Culpeper Minute Men. Organized July 17, 1775, under a large oak tree in “Clayton’s old field” (later known as Catalpa Farm).

Of the 16 military districts - Culpeper Battalion was the ONLY one to show up in Williamsburg with a full cadre of men, trained and on time. While just 350 men marched - HUNDREDS prepared them for that journey and their victories at Hampton and Great Bridge. To this day, the region that participated in the Culpeper Military District of 1775 remains the core of modern Conservative political thought and the MAGA movement in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The Committee of Safety commissioned Lawrence Taliafero, of Orange, to be the Colonel; Edward Stevens, of Culpeper, to be the Lieutenant Colonel; and Thomas Marshall of Fauquier to be the Major of this Battalion. They also commissioned ten Captains for the Companies which were to make up the Battalion, among them were: John Jameson, then Clerk of Culpeper County and a member of the Committee of Safety; Philip Clayton; James Slaughter; George Slaughter; and Capt. McClanahan, A Baptist minister, who regularly preached to his troops.

“It was the custom then to put all the Baptists in one Company, for they were among the most strenuous supporters of liberty. The Methodists went into another, according to the wishes of the Committee of Safety, which recommended that the different religious denominations each organize companies of their own kind.”

The battalion adopted uniforms consisting of hunting shirts of strong, brown lines, dyed with an extract of the leaves of trees (probably oak leaves). On the breast of each shirt was worked in large white letters the words: “LIBERTY OR DEATH.” (A wag of the times said that this was too severe for him, but that he would enlist if they could change the motto to “Liberty or be Crippled.”

Their iconic original flag included a rattlesnake with 13 rattles, coiled in the center, ready to strike. Underneath it were the words: “DON’T TREAD ON ME.” On either side were the words: “LIBERTY OR DEATH.” And at the top “THE CULPEPER MINUTE MEN.” Under this flag, these Minute Men took part in the Battle of Hampton and the Battle of Great Bridge, the first Revolutionary battles on Virginia soil. Several of the original Culpeper Minutemen were sufferers at Valley Forge.

Origins: 19 August 1775-17 December 1776

The Third Virginia Convention passed an ordinance on 19 August 1775 that grouped counties into military districts, mandated the districts to raise minute battalions, and also raise a company of regulars. The counties of Orange, Fauquier, and Culpeper were grouped together and required to raise a minute battalion of 10 companies of 50 men each. The regulars were to be a rifle company.

Officers were appointed by the newly formed Committee of Safety for the District. Lawrence Talifferro of Orange County was appointed colonel, Edward Stevens of Culpeper was appointed lieutenant colonel, and Thomas Marshall of Fauquier major. In proportion to the population of the counties, four “Minute Companies” were to come from each of Fauquier and Culpeper, and two from Orange.

At the beginning of September recruiting for all of the companies, including the company of regulars, was under way. Although the company of regulars and the minute companies began their existence together with the meeting of the district committee of safety, they very soon parted ways. Regular companies were to rendezvous at Williamsburg, whereas minute companies were to rendezvous at a location set by the District Committee of Safety, in this case, at the town of Culpeper. Records of the Committee of Safety for 18 September 1775 show the regulars under Capt. John Green drawing 15 rifles, an indication that they were already in Williamsburg. Indeed, of all of the regular companies in Virginia, Green’s was the first to arrive in Williamsburg and pass inspection. He became the senior captain of the Virginia Continental Line and his company assigned to the First Virginia Regiment on October 21st.

The Culpeper Minute Battalion was reported to be within a few hours march of Williamsburg by Purdie’s “Virginia Gazette” on October 20th, and on October 23rd the captains of the Culpeper Minute Battalion were definitely in Williamsburg starting to draw equipment. However, there were weapons for only half the Battalion. On October 24th, five companies of the Culpeper Minute Battalion were ordered to Norfolk with the Second Virginia Battalion under Col. William Woodford.

The first fighting of the Revolutionary War south of Massachusetts occurred on October 26–27, 1775, in Hampton. British naval forces under the command of Matthew Squire entered Hampton Harbor intent on bombarding and burning the town in revenge for the burning and looting of a Royal Navy tender that had gone ashore during a hurricane. Squire’s assault was met by determined opposition from Patriot forces, including riflemen from the Culpeper District Minute Battalion under the command of Colonel William Woodford, who arrived from Williamsburg early on the morning of October 27 after riding all night in a rainstorm. British and Loyalist forces withdrew after suffering multiple casualties, while the Patriot forces recorded no casualties and Hampton emerged largely unscathed. The Battle of Hampton increased the animosity between white colonists and royal governor John Murray, fourth earl of Dunmore, and emboldened Patriot leadership.

On October 26, the Committee of Safety received word that British ships are at Hampton threatening the town. Col. Woodford took a company of regulars and 50 minutemen armed with rifles under Capt. Abraham Buford to defend the town. Because the minute companies were armed with both muskets and rifles, volunteer riflemen from other companies of the Battalion replaced some of Buford’s own men who were not equipped with rifles. Buford’s men were stationed in a house and at a breastwork that had been constructed. Their accurate rifle fire soon had an effect. The sailors were unable to man their guns except where protected by netting. A British pilot boat, the Hawk Tender, was captured. The British lost 2 killed, 3 wounded, and 8 captured.

Part of the Culpeper Battalion was the rifle company raised and led by John Green, who would retire at the end of the war as a Colonial in the 10th Regiment. Green was comissioned as a regular officer on Sep. 6, 1775 and tasked with raised a company of regular rifleman. His company trained and mustered in mid September from his Culpeper county home, Liberty Hall Plantation. While a full list of men that accompanied Woolford from Williamsburg to Hampton does not existing, we do know that Green’s Rifle Company was there and another company from the newly arrived Culpeper Battalion’s rifleman. Per Edmund Pendleton’s (President of the Virginia Committee of Safety) November 16, 1775 letter to Jefferson “The life and Soul of this Corps is Capt. Green’s Company of Riflemen from Culpeper, who in three Reliefs of about 22 at a time, scour the Rivers, and have in various Attempts, prevented a landing of the enemy.

In a letter from John Page to Jefferson on November 11, 1775, Page talks about the rifleman at Hampton and how John Green dug out one of the cannon balls fired at his company and then sent it to Col. Henry.

“The Man of War fired many 6 Pounders at our Men—however but 2 of them struck near them. One went through a Stone House and the other lodged in the Bank over the Heads of our Men which they dug out and sent by Captn. Green to Col. Henry. I can assure you that about 20 Rifle Men have disputed with the Man of War and her Tenders for this Vessel 2 Days and they have hitherto kept her and the Ferry Boats safe, which it is supposed they wish to burn. It is incredible how much they dread a Rifle.”

John Page, Nov 11, 1775 letter to Thomas Jefferson

The Battle of Hampton: October 26–27, 1775

author Patrick H. Hannum

In the summer of 1775, tensions simmered between military forces loyal to Lord Dunmore and the citizens of the Tidewater. Dunmore had fled Williamsburg in June following the Gunpowder Incident and had taken refuge on the warship HMS Fowey in the York River. The Fowey was joined by the fourteen-gun sloop HMS Otter under the command of Matthew Squire, who was soon to become the senior British naval officer in the colony. With locals prohibited from selling provisions to British ships, landing parties from small warships known as tenders had been raiding settlements along the shoreline, confiscating supplies and livestock and enabling enslaved people to abscond and join Dunmore’s forces. On July 13, Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette reported that a tender from the Fowey or Otter had landed near Gloucester, disgorging several armed men “who stole 14 sheep and a cow.” On July 15, Dunmore relocated his flotilla to Norfolk, where it continued to operate throughout the waterways of Hampton Roads, intensifying tender raids on suspected rebel strongholds. By early September, the flotilla included the Otter, the HMS Mercury, which replaced the Fowey, and three commercial vessels that Dunmore’s supporters outfitted as warships, all of them supported by tenders.

Map of Williamsburg, York, Hampton, and Portsmouth

On September 2, Squire was aboard the Otter’s tender, Liberty, when it was driven ashore by a hurricane and grounded in the mudflats of the Back River, an inlet of the Chesapeake Bay near Hampton. Squire and the Liberty’s pilot, Joseph Harris, a formerly enslaved man, escaped to the shore, where Harris procured a canoe and rowed himself and Squire back to the Otter. Thirteen other crew members, including formerly enslaved people at risk of reenslavement or death, were not so lucky. Elizabeth City County militia forces seized the crewmen as well as weapons—including six swivel guns, muskets, and cutlasses—ammunition, and naval stores. Then they set fire to the Liberty in what the Virginia Gazette described as payback for Squire’s “harbouring gentlemen’s negroes, and suffering his sailors to steal poultry, hogs, &c.”

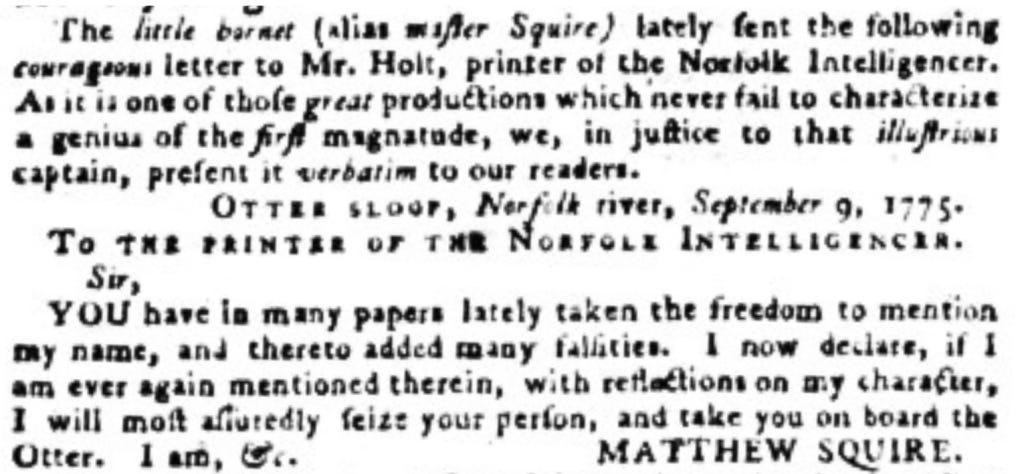

Virginia Gazette Goads Matthew Squire

The white crewmen were eventually freed, but the Black crewmen were reenslaved, and Squire demanded the return of the weapons and supplies and what was left of the Liberty. Failure to comply, he wrote in a letter printed in the local newspapers, meant that “the people of Hampton, who committed the outrage, must be answerable for the consequence.” A war of words followed, with local officials arguing that the weapons and stores had been abandoned and refusing to give up the Liberty’s gear unless Squire returned Harris and the other enslaved people who had sheltered with Dunmore. When the editor of the Virginia Gazette and Norfolk Inquirer attacked Dunmore’s father for his role in the Jacobite Rebellion and implied that Squire had been “too free with people sheep and hoggs” during the recent seizure of a vessel, the infuriated Dunmore seized the Gazette’s press and moved it to his ship, where he printed his own newspaper to counter the Patriot narrative.

With neither side backing down, Squire began planning an attack on Hampton as retribution. Aware of his intent, local authorities fouled the channel of the Hampton River with sunken vessels to prevent British ships from entering the small harbor. Local militia were defending Hampton, but they lacked the numbers, training, weapons, and leadership to deflect a serious attack. On September 12, 100 volunteers from the Williamsburg militia guard joined the local forces; when those volunteers returned to Williamsburg, they were replaced by 100 volunteers under the command of Major Francis Epps of the 1st Virginia Regiment. Following a series of raids by Dunmore’s forces in the Norfolk area, the Virginia Committee of Safety replaced the volunteer units with Captain George Nicholas’s company of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and Captain George Lyne’s company from the Gloucester District Minute Battalion.

On the night of October 25, Squire led a raid by four tenders on homes at Mill Creek, just outside the entrance to Hampton River. The next day, he attempted to enter the river but found the entrance blocked by the sunken vessels. He also encountered opposition from thirty of Lyne’s men deployed on one side of the channel and twenty-five of Nicholas’s men on the other, as well as from local militia. It is unclear which side fired first, but the Patriots discharged their muskets, and the tenders—located only about 300 yards offshore—returned fire with four-pound cannon loaded with ball and grapeshot. After about an hour, Squire’s forces withdrew.

Later on October 26, an express rider from Hampton delivered a message to the Virginia Committee of Safety in Williamsburg requesting immediate reinforcements to counter the British attempt to enter the harbor. Colonel William Woodford left Williamsburg at 9:00 that evening with fifty volunteer riflemen from the Culpeper District Minute Battalion, led by Captain Abraham Buford, supported by wagons and horses provided by the citizens of Williamsburg. They traveled the thirty miles to Hampton in a heavy rainstorm, arriving about 7:30 the following morning.

By 8:00, the British tenders had cleared the channel. Squire sent the four tenders into the harbor while he kept the larger Otter outside the entrance. Hearing gunfire, Woodford directed his riflemen, carrying weapons accurate to 300 yards or more, to the second story of houses near the harbor and to breastworks along the wharf. A steady exchange of fire ensued. The riflemen killed or wounded several crew on the tenders, forcing them to stand off. One of the tenders, the Hawke, was captured when it got too close to shore. After an hour, Squire withdrew his forces, abandoning plans to destroy Hampton, which escaped the battle largely unscathed. The first fighting of the Revolution south of Massachusetts was over.

The Royal Navy and auxiliary Loyalist forces suffered their first casualties at Hampton, with estimates varying from a couple to many. Lieutenant John Wright, the commander of the Hawke, was injured but jumped overboard and escaped with the aid of Joseph Harris. Two members of the Hawke’s crew were killed, as was one additional man; two other men were injured and captured but recovered. One white woman was also captured. The Patriot force of more than 200 men suffered no casualties despite experiencing sustained cannon fire well within range.

Naval Swivel Gun Associated with the HMS Otter

Thomas Jefferson said that the Battle of Hampton threw white Virginians into “a perfect phrensy,” further hardening the colonists’ animosity toward the British government. The Patriots’ military success emboldened Virginia’s political leadership and highlighted the importance of information as a tool in warfare as well as the value of the rifle. The victory also demonstrated that even in the absence of a navy, determined Patriot defenders under the proper circumstances could repel British amphibious landings and inflict casualties on the landing force.

By the end of the first week of November 1776, it was clear that half the Culpeper Minute Battalion could not be equipped. On November 8th, The Committee of Safety ordered the Commander-in-Chief of the Virginia forces, Col. Patrick Henry, to discharge the remainder of the Culpeper Minute Battalion from duty at Headquarters. The married men were discharged and single men joined other companies. Col. Taliaferro led half the Battalion home while Lt. Col. Stevens remained to lead five companies to Norfolk under Col. Woodford of the 2nd Virginia. By November 15th Woodford’s troops were equipped and on the march.

The Battle of Great Bridge: December 9, 1775

The Battle of Great Bridge was fought on December 9, 1775, in the area of Great Bridge, Virginia, and is often considered the first major battle of the American Revolutionary War in Virginia, as well as a significant early victory for the Patriot forces. The conflict arose from escalating tensions between Virginia colonists and British authorities, particularly Royal Governor Lord Dunmore, who had fled Williamsburg in June 1775 and taken refuge in Norfolk aboard a Royal Navy vessel.

Dunmore fortified the bridge across the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River, a critical crossing on the road from Norfolk to North Carolina, constructing Fort Murray on the Norfolk side and deploying British regulars, Loyalist militia, and the newly formed Ethiopian Regiment composed of enslaved people promised freedom by Dunmore’s November 7, 1775, proclamation.

Colonel William Woodford led a growing Patriot force of nearly 900 men, including Virginia militia and North Carolina riflemen, who had established entrenchments on the southern side of the bridge. Dunmore, fearing the Patriot buildup and believing the rebels were poorly armed, launched a surprise attack at dawn on December 9, 1775, intending to break the Patriot lines. The British advance across the narrow causeway was met with devastating fire from the Patriot militia, including a decisive volley from the Culpeper Minutemen positioned to rake the British on the causeway. Captain Charles Fordyce, leading the grenadiers, was killed during the assault, and the British forces suffered heavy casualties, with estimates of 62 to 102 killed or wounded, while the Patriots reported only one wounded. The attack collapsed, and the British retreated to Fort Murray, abandoning the fort that evening after spiking their cannons.

Sketch by Lord Rawdon of the battlefield

The Patriot victory at Great Bridge effectively ended British control over Virginia, forcing Dunmore to evacuate Norfolk and flee to his ships in the Elizabeth River, marking the final removal of royal authority from the colony. The battle is often described as a “second Bunker’s Hill affair” by Woodford and is considered a defining moment in the American Revolution, demonstrating that colonial militia could successfully confront professional British troops. The victory also emboldened the Virginia Convention, which four days later adopted a public declaration expressing a spirit of independence, and led to the formation of the first black fighting force in American history, the Ethiopian Regiment, which fought for liberty under British command. The site, now part of the independent city of Chesapeake, Virginia, is recognized as a historic landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Woodford quickly moved to Norfolk and intermittent fighting occurred between the American forces on land and the British forces on ship. On January 1st the British landed soldiers who set fire to Norfolk. Virginia troops burned most of the remaining houses. On January 2nd some of the Battalion was discharged to return home. Two of Capt. Buford’s men were killed on January 21st by a cannonball. The balance of the regiment was sent home in late March. Capt. William Pickett’s Company from Fauquier were paid through April 2nd, 1776.

The Council of the State of Virginia called two battalions of minute men into service on August 10th, 1776. Unlike the order of 1775, the call was made for companies from six different districts. Culpeper was required to provide two companies. One was a company commanded by Capt. James Nash and was in service at least from August 19th to August 22nd. The other company appears to have been under Capt. Abraham Buford. The men were stationed near Jamestown, where many of the men became sick and some died. The dominant sickness was epidemic typhus (”camp fever”), worsened by dysentery and smallpox, in filthy, overcrowded conditions at Jamestown hospital in 1776. It killed hundreds of Virginia soldiers before they could fight, and Culpeper Minute Men veterans were among the hospitalized — many died before joining Washington’s main army. In addition, others died from Dysentery (bloody flux) from contaminated water/food as well as Smallpox, which was widespread in Virginia. Smallpox was so common that inoculation began late 1776 under Washington’s orders.

The last date of documented active service for the Culpeper Minute Battalion was when Lt. Elijah Kirtley drew rations and forage from October 3rd to November 20th, 1776. Minute battalions throughout the state lost officers and men to the newly forming continental regiments as well as the Virginia State Line in 1776. On 17 December 1776 the House of Delegates passed an ordinance abolishing the minute battalions.

Although in existence for only about a year and a quarter, the Culpeper Minute Battalion had a major impact on the American Revolution. It was involved in engagements at Hampton, Great Bridge, and Norfolk and did garrison duty at Jamestown. The engagement at Great Bridge was a strategic victory making it inevitable that Lord Dunmore would have to abandon Virginia. Virginia was free to provide critical troops and provisions both to the North and South until 1781, when the enemy returned to Virginia. Without this support from Virginia, the outcome of both northern and southern battles of the Revolution could have been very different.

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it

George Santayana

The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense, 1905.

Culpeper station, home to the Museum of Culpeper History, is a train station built in 1904 by the Southern Railway, replacing an 1874 station house which itself replaced two stations originally built by the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. It is currently served by Amtrak‘s long-distance Cardinal and Crescent routes, along with two daily Northeast Regional trains with final stops in New York or Boston to the north and Roanoke to the south.

When then-owner Norfolk Southern Railway tried to demolish a portion of the depot in 1985, a citizens’ committee formed to save the building. In 1995, the town successfully prepared a $700,000 renovation grant under the Virginia Department of Transportation Enhancement Program. Three years later, Norfolk Southern sold the depot to the town, and in 2000 the renovated building opened to the public. Additional work to the freight section was completed in 2003.

George Washington also surveyed in Fauquier County. I was raised on a farm in Middleburg. The plantation house was burned during the Civil War and the Pickett family moved into the abandoned slave quarters which were added onto over the next 150 years. When my family bought the place and renovated the house in the 1960s, we found the original King George Grant for 10,000 acres of land in a strong box in the floor ... signed and surveyed by GW. By then "Fieldmont" was down to 350 acres! Still a LOT to ride over and then into the adjoining Bull Run Mountains.

It’s such an amazing history America has. So important to have and share these records. It’s inspiring to think of these courageous men, in large organized groups, standing up against tyranny, saying we will not comply too the point that death is more acceptable than the loss of freedom. So many people today are so pampered, they willingly hand their sovereignty and their families sovereignty over for the idea of security. As Ben Franklin said “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety". We could sure use a couple hundred thousand old school patriots today. Thanks Drs. Malone for sharing this interesting piece of history.