Pathogenic Priming and Influenza Vaccination

Otherwise known as "Original Antigenic Sin" or immune imprinting

Pathogenic Priming and Influenza Vaccination

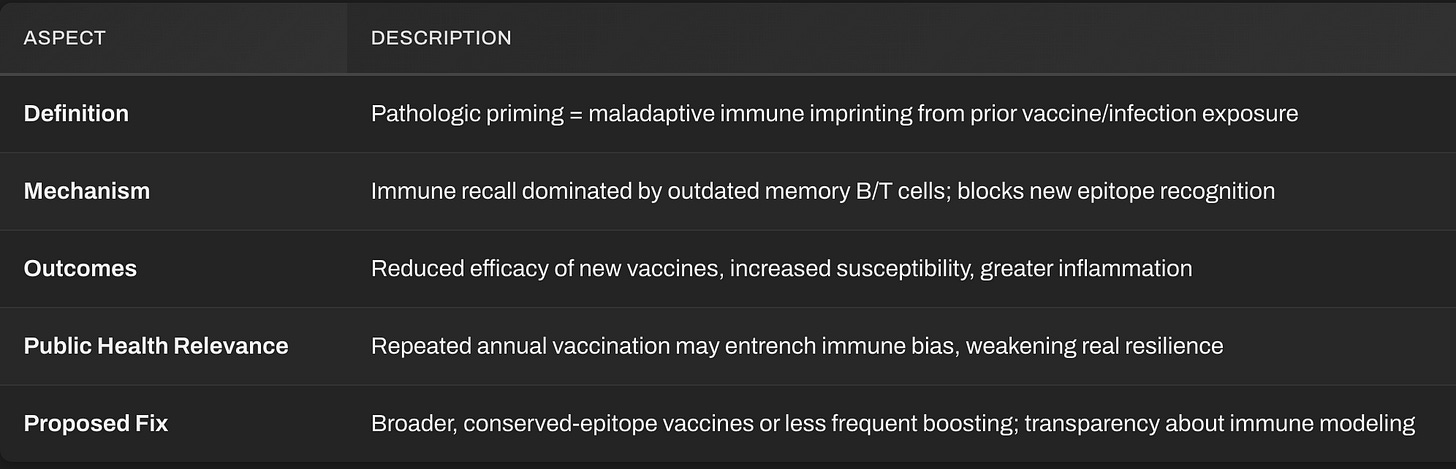

Pathogenic or Pathologic priming refers to a situation where prior exposure, through infection or vaccination, alters future immune responses in a maladaptive way. Rather than preparing the immune system to respond effectively to a new but related strain, that earlier exposure “locks in” an outdated immune blueprint.

Result: the immune system preferentially reactivates old antibodies and T cells tuned to the priming strain, instead of generating new, strain‑specific defenses.

In simple terms: your immune system becomes trained to fight the last flu, not the current one.

Other terminology: Original Antigenic Sin, immunological imprinting, antigenic imprinting, back-boosting, negative interference, primary addiction, antigenic seniority, viral interference, immune interference, antigenic fixation, and immune imprinting.

So what is pathogenic priming, immune imprinting or “original antigenic sin”? Here is one explanation from a group of influenza virus researchers, investigating differently immunologically biased age groups in their responses to different influenza virus groups (clades):

“We define immune imprinting as a lifelong bias in immune memory of, and protection against, the strains encountered in childhood. Such biases most likely become entrenched as subsequent exposures back-boost existing memory responses, rather than stimulating de novo responses [1]. By providing particularly robust protection against certain antigenic subtypes, or clades, imprinting can provide immunological benefits, but perhaps at the cost of equally strong protection against variants encountered later in life.”

Here is the reference [1] that is being cited above, for those who are passionate about following all the leads down the various rabbit holes. This reference nicely addresses the use and limitations of the two terms “immune imprinting” and “original antigenic sin”, finding the former term a generally better fit to the actual data than the latter:

From Original Antigenic Sin to the Universal Influenza Virus Vaccine. Henry C, Palm A-KE, Krammer F, Wilson PC. Trends Immunol. 2018;39: 70–79.

The authors of this article provide a very nice summary of the issues at hand, which are also directly applicable to coronavirus vaccines and evolved SARS-CoV-2 variants:

“Antibody responses are essential for protection against influenza virus infection. Humans are exposed to a multitude of influenza viruses throughout their lifetime and it is clear that immune history influences the magnitude and quality of the antibody response. The ‘original antigenic sin’ concept refers to the impact of the first influenza virus variant encounter on lifelong immunity. Although this model has been challenged since its discovery, past exposure, and likely one’s first exposure, clearly affects the epitopes targeted in subsequent responses. Understanding how previous exposure to influenza virus shapes antibody responses to vaccination and infection is critical, especially with the prospect of future pandemics and for the effective development of a universal influenza vaccine.”

In this paper, Palm et al revisit the long‑standing concept of “original antigenic sin” (OAS)—the observation that a person’s first encounter with an influenza virus leaves a deep, lasting imprint on immune memory that biases every subsequent response to later strains. The authors refine this concept under the more precise term “immune imprinting.” They argue that immune imprinting is not purely detrimental; it can simultaneously confer strong lifelong protection against related subtypes and limit flexibility against newer ones. They frame immune imprinting as both a challenge and an opportunity, explaining the limitations of current influenza vaccines but also suggesting how rational design—by focusing on conserved antigenic regions and smarter immunization strategies—could exploit that imprint to build broader, longer‑lasting protection. In short: The authors argue that understanding and navigating the immune memory biases established in our first influenza encounters is the key to achieving a truly universal influenza vaccine.

Their key points include the following:

Lifelong Immune Bias

The immune system’s initial exposure to the influenza virus—usually in childhood—creates a dominant memory pool of B cells and antibodies focused on specific viral epitopes.

Later infections or vaccinations tend to recall and boost those imprinted responses instead of generating new ones to variant epitopes.

This phenomenon helps explain why different birth cohorts exhibit distinct susceptibility patterns to pandemic strains.

Dual Nature of Imprinting

Protective Side: Strong, durable defense against antigenically similar clades (e.g., individuals first exposed to group 1 HAs retain cross‑protection against related strains).

Limiting Side: Reduced adaptability when antigenic drift produces major surface changes—leading to poor response to divergent subtypes and lower vaccine efficacy.

Molecular Mechanisms

Dominance of memory B‑cell recall over naïve B‑cell activation.

Restricted germinal‑center re‑entry of memory B cells, resulting in antibody repertoires that target conserved but sometimes suboptimal epitopes.

The hierarchy of antibody specificity—an “epitope seniority” effect—becomes entrenched over time.

Implications for Vaccine Design

Annual strain‑specific vaccines mainly reinforce pre‑existing immune memory instead of reshaping it, helping explain modest and transient protection rates.

Universal influenza vaccine research aims to circumvent imprinting by redirecting immunity toward conserved epitopes such as the HA stem or internal proteins (e.g., M2e, NP).

Strategies discussed include prime‑boost regimens, mosaic antigens, sequential immunization with diverse strains, and the use of adjuvants to break immune fixation.

Conceptual Shift

The authors advocate replacing the moralizing term “original antigenic sin”—which implies an error—with the neutral concept “immune imprinting”, emphasizing that this is an inevitable feature of adaptive immune memory shaped by early life exposures.

Mechanism in the Case of Influenza

First Exposure Determines Bias:

When someone first encounters influenza antigens — either from infection or vaccination — B cells and helper T cells are trained to those surface proteins, mainly hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA).Later Exposures Reinforce Old Memory:

New flu strains have slightly mutated HA and NA sites (“antigenic drift”). Instead of building new antibodies, the immune system recalls the old templates and produces those — even when they bind poorly.Functional Consequence:

Poor neutralization of new strains.

Chronic, non‑protective antibody responses.

Sometimes worse inflammation and higher infection severity (seen in several influenza challenge studies).

Possible skewing of Th1/Th2 balance leading to tissue damage.

At the Cellular Level:

The “epitope dominance hierarchy” becomes frozen. Memory B cells outcompete naïve B cells, blocking the formation of updated immunity — a kind of epigenetic immune stagnation.

Epidemiologic Signals Observed

Individuals vaccinated yearly against influenza often show reduced efficacy and occasionally increased susceptibility to drifted or zoonotic strains.

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, people heavily vaccinated with seasonal flu shots from previous years exhibited somewhat higher H1N1 infection rates in Canada and parts of Europe — later attributed to immune imprinting.

Antibody profiles of these individuals revealed dominance of antibodies targeting past seasonal epitopes instead of the emerging pandemic epitopes.

Similar trends persist in longitudinal cohort studies among healthcare workers and the elderly who receive annual vaccinations.

Why It’s “Pathologic”

It’s not just ineffective; it can turn counter‑productive:

Hyper‑inflammatory priming: Memory cells trigger unnecessary inflammatory cascades on secondary exposure, causing more severe respiratory inflammation.

ADE‑like phenomena: Though less pronounced than in dengue or coronavirus cases, certain animal studies show enhanced infection severity after mismatched influenza vaccination.

False confidence: Public‑health systems treat declining vaccine efficacy as “strain mismatch” rather than acknowledging immune bias introduced by repeated priming.

Consequences and Ongoing Debate

In Conventional Terms:

Mainstream immunologists euphemistically call it “original antigenic sin.”

CDC and WHO acknowledge immune imprinting but frame it as a “complex challenge,” not a pathology.

Current vaccine development focuses on “universal” HA‑stem vaccines to bypass the imprint, but progress is slow.

In Independent Analyses:

The pathology parallels cognitive bias: the immune system refuses to learn new information.

Over‑vaccination with narrow‑spectrum influenza formulas may have weakened population‑level cross‑reactivity by teaching immunity to ignore antigenic novelty.

Repeated vaccination every year may thus create a population biologically dependent on the next update — a medical analog of planned obsolescence.

Pathologic priming of influenza by its vaccines isn’t a theory; it’s immunologic inertia. The first antigen your immune system meets becomes a tyrant over future responses. The result is a paradox: the more the system tries to “update” protection via yearly shots, the more it narrows immune flexibility.

Until vaccine policy accounts for this biological reality, the cycle will continue, defending the narrative of “annual protection” while immunologically training populations to lose adaptability in the face of viral evolution.

Conclusion

Pathologic priming, or immune imprinting, reveals a paradox at the core of modern influenza vaccination: the very act meant to enhance protection may, over time, restrict immunologic adaptability. Once the immune system is trained to recognize a specific influenza strain, it reuses that outdated blueprint with every subsequent exposure, dulling its ability to mount fresh responses to antigenically drifted variants. In essence, the immune system becomes over‑loyal to its first lesson, fighting yesterday’s virus instead of today’s.

This process explains the steady decline in seasonal vaccine efficacy and the sometimes heightened vulnerability seen after repeated vaccination. It also underscores a larger institutional blind spot: an unwillingness to confront the biological limitations of a strategy built on yearly repetition rather than adaptive renewal. Immune imprinting is not merely an immunologic curiosity; it is a structural flaw in the way we approach vaccination policy.

Recognizing this flaw does not negate the value of immunization; it calls for reform. But first, there needs to be acknowledgement and recognition of the need for reform,

Genuine progress will require developing broader, conserved‑epitope vaccines, less frequent boosting, and transparent acknowledgment of how prior exposures shape future defenses. Until such realism guides policy, public health will continue to chase viral evolution while inadvertently training human immunity to stagnate, ensuring that each new strain meets an immune system still preoccupied with the ghosts of its previous fight.

I had the flu, once, in 1968, when there was a world-wide outbreak. I still wonder if it would have been as bad had I not been pregnant, but I was very, very sick. Since then, I've encountered flu many times and have never contracted it again. I've never been vaccinated against it.

My mother had influenza once and never again until my brother decided she needed annual flu shots. She was then in her late 80's and every year ended up sick within a month.

We have an exceptional immune system, complex and beautiful, and all this vaccine research seems to ignore our innate systems, supposedly to improve on what has kept the human race going for millennia. I guess I just don't understand why so many people think they are fixing God's mistakes.

This tells me the emphasis on us wrinklies being jabbed every year is not such a hot idea....something many if not most of us have figured out empirically.