Spain’s African Swine Fever Crisis

A Laboratory Investigation and Global Pork Industry Threat raise concerns about another Gain-of-Function research lab leak

Spain’s African Swine Fever Crisis: A Laboratory Leak Investigation and Global Pork Industry Threat

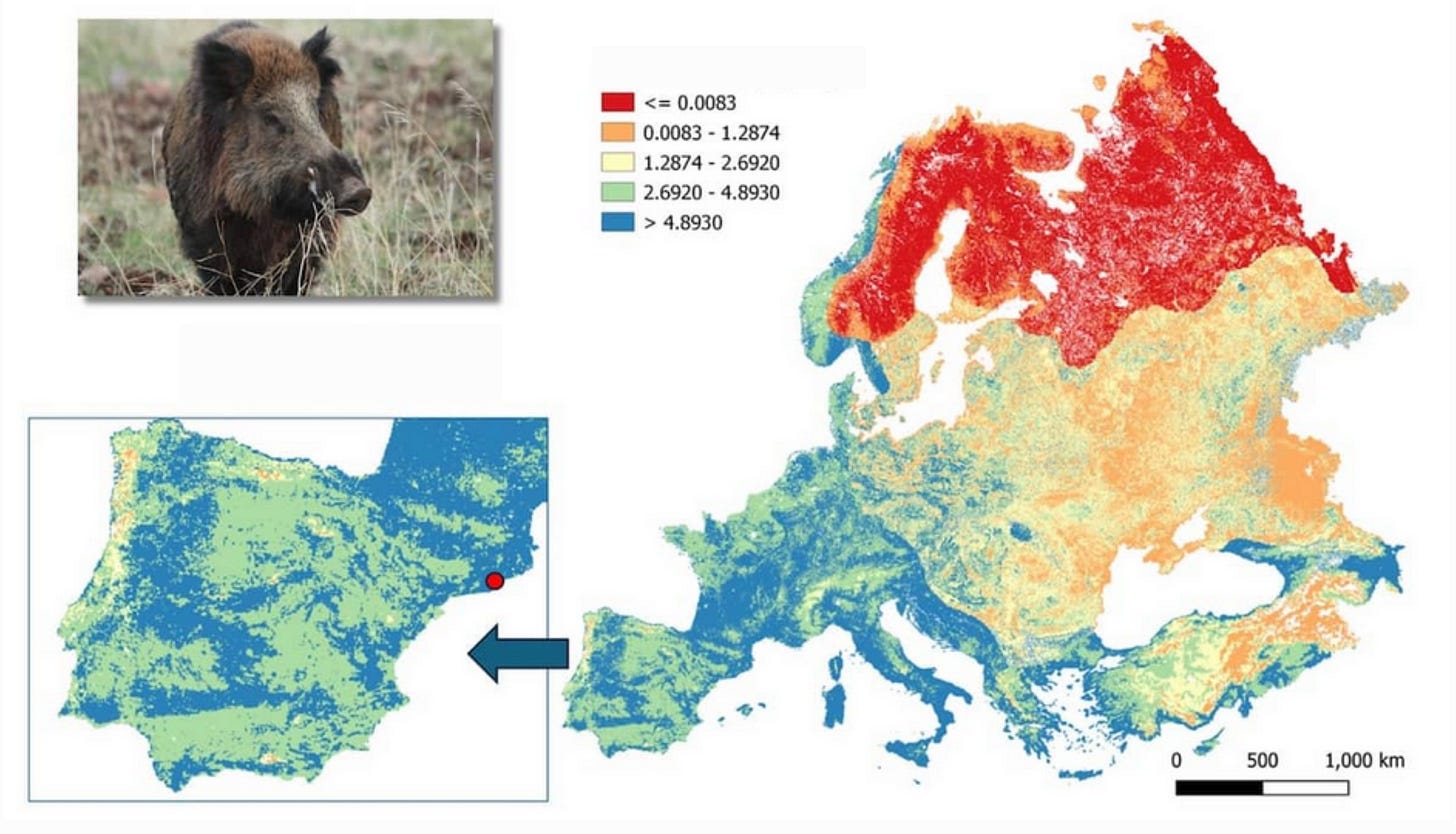

In late November 2025, Spain faced an unwelcome return of a devastating animal disease that hadn't been seen in the country for over 30 years. African swine fever, a virus that kills pigs with frightening efficiency, was discovered in wild boars near Barcelona, sending shockwaves through Spain's massive pork industry and raising uncomfortable questions about how it got there—including the possibility of a laboratory accident.

Laboratory Leak Déjà Vu: Spain’s African Swine Fever Crisis Echoes Wuhan Coronavirus Controversy

Spain’s 2025 African swine fever outbreak bears striking parallels to the Wuhan Institute of Virology coronavirus debate that dominated global headlines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Once again, a dangerous pathogen has emerged near a high-security research laboratory that is working with the exact type of virus found in the outbreak, raising uncomfortable questions about laboratory safety and the risks of international pathogen research collaborations.

Like the Wuhan controversy, the Spanish case involves a laboratory conducting virus manipulation research under international funding arrangements. IRTA-CReSA, located just 150 meters from where the first infected wild boars were discovered, had been working with the African swine fever virus as part of extensive collaborations with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plum Island Animal Disease Center. The five-year cooperative agreement specifically focused on “genetic manipulation of virus genome” to create “novel attenuated strains”—work that requires creating modified viral variants in laboratory settings.

The genetic evidence intensifies the parallel: Spanish investigators found that the outbreak strain closely matches a laboratory reference virus from Georgia (2007) commonly used in research facilities, rather than strains currently circulating in European wild populations. This discovery prompted dramatic police raids, criminal investigations into potential environmental crimes, and court-sealed proceedings—echoing the intense scrutiny and speculation that surrounded the Wuhan laboratory.

Both cases highlight the inherent tensions in international pathogen research: the legitimate need for vaccine development and disease preparedness versus the risks of accidental release from high-containment facilities. Both involve complex oversight questions when multiple governments fund research on dangerous pathogens, and both have triggered debates about transparency, accountability, and the balance between scientific advancement and public safety.

However, there are important regulatory differences. While the Wuhan controversy centered on pandemic pathogen policies and human health risks, the Spanish case involves agricultural biosecurity and livestock threats and falls under different oversight frameworks. Yet the fundamental questions remain eerily similar: How do we conduct necessary but dangerous research while minimizing risks? Who bears responsibility when international collaborations go wrong? And how do we maintain public trust in scientific institutions when laboratory accidents become global crises?

The Spanish outbreak may well become this decade’s defining case study in laboratory safety—a sobering reminder that the Wuhan controversy was not an isolated incident, but perhaps a preview of challenges to come as pathogen research becomes increasingly international and sophisticated.

The following comprehensive analysis examines how Spain’s African swine fever crisis has evolved from an agricultural emergency into a complex investigation involving laboratory safety, international research collaborations, and the delicate balance between scientific progress and public protection.

Spain’s Pork Powerhouse at Risk

To understand why this outbreak matters so much, you need to know that Spain isn’t just any pork producer—it’s a global giant. The country is Europe’s largest pork producer and the world’s third-largest, exporting nearly 3 million tons annually to over 100 countries. This industry is worth €8.8 billion (about $10.2 billion) each year and employs thousands of people across the country.

China alone buys almost half of Spain’s pork exports, making international trade relationships crucial to the industry’s success. When a disease like African swine fever appears, these valuable export markets slam shut almost immediately as countries protect their own pig populations.

The Laboratory Connection and Genetic Evidence

The outbreak began with a disturbing discovery: dead wild boars found in a wooded area just outside Barcelona. What made this particularly puzzling was the location—the infected animals were found just 150 meters away from IRTA-CReSA, a high-security animal research laboratory that had been actively working with African swine fever virus.

Initially, officials suggested the outbreak might have started when a wild boar ate contaminated food, perhaps a sandwich discarded by a truck driver. But when scientists analyzed the virus’s genetic makeup, they found something unexpected. The strain infecting the Spanish wild boars wasn’t related to viruses currently spreading elsewhere in Europe. Instead, it closely matched a laboratory reference strain from Georgia, dating back to 2007—the exact strain commonly used in research facilities for vaccine development and experimental studies.

The genetic analysis, conducted by the Centre for Animal Health Research (CISA-INIA), a European Union reference laboratory near Madrid, revealed that the virus “closely resembles a strain that circulated in Georgia in 2007—the same strain commonly used in experimental studies and vaccine development.” This finding intensified scrutiny of IRTA-CReSA, particularly since the first infected wild boars were found near its facilities.

The Police Investigation

The suspicions raised by the genetic evidence led to dramatic action. Spanish police raided the IRTA-CReSA laboratory following a court-issued search warrant as part of an investigation into potential environmental crimes related to the outbreak. Officers from both the Mossos d’Esquadra (Catalonia’s regional police force) and the Guardia Civil entered the facility, with the proceedings placed under court seal.

The laboratory is one of five animal research centers located within 20 kilometers of where the outbreak was first detected, but its proximity to the initial cases and its active work with African swine fever virus made it a focal point of the investigation. The regional Catalan government has commissioned an independent audit of IRTA-CReSA to determine whether the outbreak could have originated from any nearby research facilities.

A joint investigation team comprising regional police officers and Seprona, the Guardia Civil’s environmental protection unit, continues working to establish how the virus may have escaped laboratory containment, if that scenario is confirmed.

The Stakes Couldn’t Be Higher

So far, the outbreak has been contained to wild boars—no commercial pig farms have been infected. This is crucial because if the virus reaches domestic pig populations, the consequences would be catastrophic. Entire farms would need to be depopulated, with all animals killed and disposed of to prevent spread.

The economic ripple effects extend beyond large commercial operations. In regions like Mallorca, which normally exports about 1,000 pigs weekly to Catalonia, potential movement restrictions could force all that production to stay on the island, disrupting local markets and affecting prices during the busy Christmas season.

Gain-of-Function Research Concerns

While no direct evidence has emerged of gain-of-function research; experiments that deliberately enhance a pathogen’s dangerous properties like transmissibility or virulence, the incident has renewed discussions about the risks of working with dangerous pathogens. The documented USDA-IRTA research program involved creating “attenuated” virus strains, which means developing variants that are deliberately weakened rather than enhanced. However, this type of work still requires extensive manipulation of viral genomes and the creation of new viral variants.

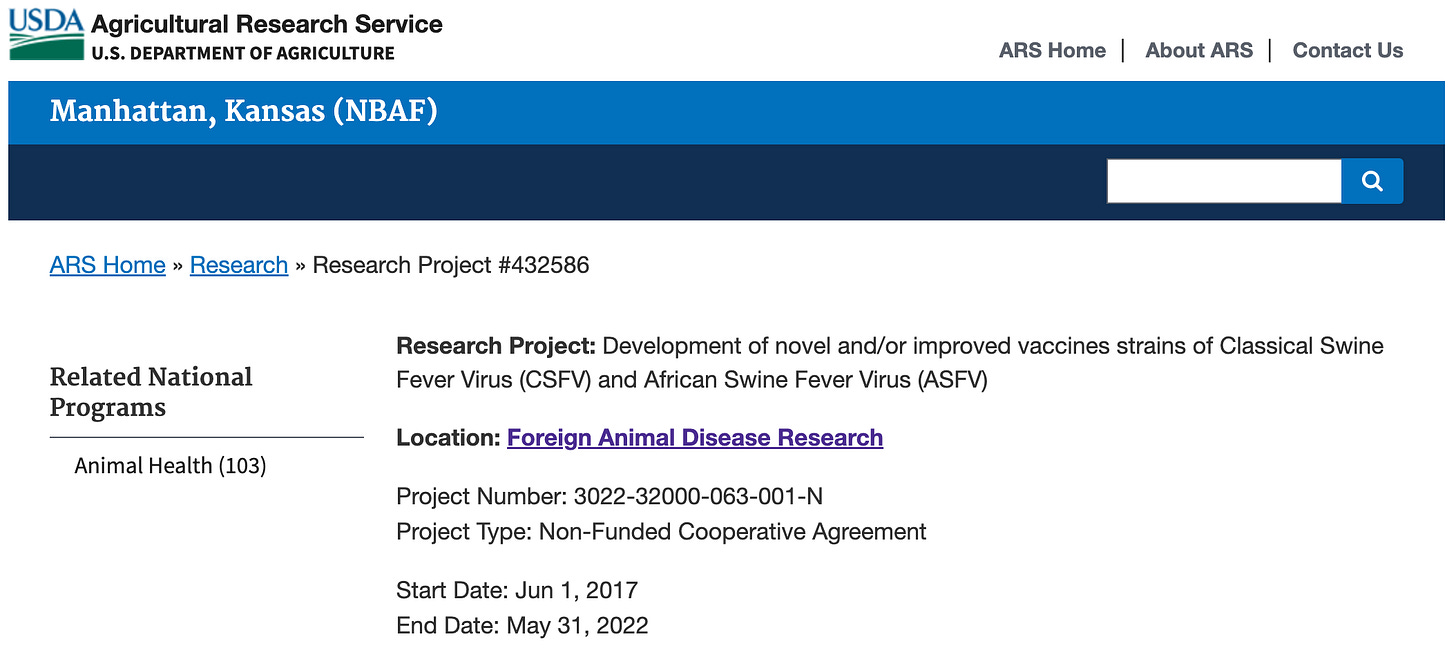

The USDA description of the scope of work for “Development of novel and/or improved vaccines strains of Classical Swine Fever Virus (CSFV) and African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV)” in cooperation with both Plum Island and the IRTA-CReSA uses language that appears to describe gain-of-function research:

Specific objectives include:

“A. ARS, PIADC will provide expertise in the development of ASFV live attenuated vaccine strains. Modification of ASF strains will be performed by genetic manipulation of virus genome and homologous recombination methodology. ARS, PIADC will produce pilot experiments towards the evaluation of attenuation and immunogenicity of the developed viruses.

B. IRTA will provide expertise in the development ASFV recombinant viruses. IRTA will design and help in the development of novel attenuated strains based on the template of vaccine strains already developed by IRTA. IRTA will also participate in evaluating protective effect of the developed vaccine strains.”

Staff from IRTA-CReSA have previously participated in academic discussions on the ethics of gain-of-function research, highlighting the ongoing scientific debate over the risks and benefits of such work. The research activities at IRTA-CReSA appear to focus on legitimate public health goals: understanding how the virus works, developing diagnostic tools, testing vaccine candidates, and studying transmission routes.

However, the proximity of the outbreak to an active research facility working with the exact viral strain found in the wild boars, combined with the extensive virus manipulation work documented in the USDA cooperative agreement, has raised inevitable questions about laboratory safety protocols and oversight.

This incident occurs against a backdrop of increased global scrutiny of high-containment laboratory work following debates about the origins of COVID-19 and concerns about laboratory biosafety. Even when research aims are purely beneficial, like vaccine development, the risks of accidental release remain a concern for communities and policymakers worldwide.

Comparison to Wuhan Laboratory Oversight Failures

Compared with the Wuhan-lab oversight debates, U.S.-funded swine fever research at a facility like IRTA-CReSA falls into a different regulatory category and therefore raises different compliance questions. The Wuhan controversy centered on whether NIH-supported coronavirus work in China involved experiments that could enhance human-pandemic pathogens and whether those activities were properly classified, reviewed, reported, and monitored through foreign subawards; the key oversight friction points were pandemic-pathogen policy triggers (such as P3CO/ePPP review), transparency, and enforceability of U.S. grant conditions abroad.

By contrast, U.S. support for classical or African swine-fever work, pathogens that primarily threaten livestock rather than humans, would normally fall under agricultural-biosecurity and select-agent-style controls and cooperative-agreement oversight rather than pandemic-pathogen review. As a result, a compliance problem in the IRTA-CReSA context would most likely hinge on whether grant or contract terms, reporting obligations, or select-agent/security requirements were violated, not on the same pandemic-pathogen enhancement classification disputes that drove the Wuhan debates.

In most scenarios involving U.S.-funded foreign pathogen research, an investigation of potential violations of U.S. rules and policies would start with the Office of Inspector General of the funding agency (e.g., USDA OIG if USDA funded the work). The appearance of conflict of interest and the tendency to minimize the importance of these events argue against USDA managing the investigation. From there, it would likely become a multi-agency review involving USDA, HHS/NIH (if applicable), select-agent authorities, and potentially DOJ if legal violations were suspected.

Immediate Consequences

The impact was swift and severe. Within days of the announcement, about one-third of Spain’s export destinations banned Spanish pork products. Major buyers like China, the UK, Mexico, and Canada either completely suspended imports or severely restricted them. For a country that depends heavily on pork exports, this represented an economic catastrophe in the making.

The response was equally dramatic. Spain deployed over 100 military personnel to join 300 regional officials in containing the outbreak. They established exclusion zones around the affected area, banned hunting and leisure activities within a 20-kilometer radius, and used thermal drones to track and test wild boars. The outbreak has resulted in 26 wild boar deaths and prompted authorities to impose restrictions across parts of Barcelona province.

IRTA-CReSA Laboratory Construction Activities

A significant complication in the investigation has been the revelation that IRTA-CReSA was undergoing major construction work at the time of the outbreak. The laboratory was constructing a new building adjacent to its existing high-security facility, raising questions about whether construction activities could have compromised containment protocols.

The expansion work was described as being “in an initial phase” and limited “only to preliminary work preparing the terrain and urbanization of the surrounding area,” with officials insisting “only external preparatory work” had been done. The center clarified that no work was being done “on the biosecurity building or any of the operational facilities”.

However, the scope and duration of the construction raised concerns among investigators. Reports indicated that the construction company Rogasa had been executing work at the facility for three months before the outbreak was detected. According to the laboratory statement, the two buildings would be connected through two connection points, planned exclusively for the final phase of construction in 2028.

The construction work was not without incident. Since the beginning of construction work, the only recorded incident was a brief cut in gas supply, which “in no case had any impact on security or research activity” and only resulted in “temporary thermal comfort disruption for center personnel”. While laboratory officials dismissed this as minor, investigators have examined whether even temporary disruptions to building systems could have affected containment protocols.

Agriculture Minister Òscar Ordeig mentioned construction work “near” the IRTA-CReSA facilities and confirmed that the expert group studying the outbreak’s origin would analyze whether they had any relationship to the virus spread. The timing of construction activities during active virus research has become a key focus of the investigation.

Adding to concerns about the construction company’s track record, Rogasa has a history of construction problems and controversies, including being fined 590,000 euros by a Spanish court for deficiencies in building delivery and involvement in corruption investigations. While the laboratory stated that the construction management was “specialized in biocontainment” and had “extensive accredited experience in this field”, the company’s troubled history has raised additional questions about construction quality and oversight.

The construction activities have become an integral part of the investigation, with authorities examining whether any disruption from the building work; whether from the gas supply interruption, ground excavation, or other construction-related activities, could have contributed to a potential laboratory accident that allowed the virus to escape containment.

USDA Swine Fever Research

The scope of international collaboration on swine fever research at IRTA-CReSA extends well beyond project-specific funding to include comprehensive vaccine development programs. A formal USDA Agricultural Research Service cooperative agreement (Project Number 3022-32000-063-001-N) ran from June 2017 to May 2022, establishing a partnership between the USDA’s Plum Island Animal Disease Center and IRTA-CReSA specifically focused on developing “novel and/or improved vaccines strains of Classical Swine Fever Virus (CSFV) and African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV).”

This five-year cooperative agreement outlined an ambitious research program using “recombinant virus technology” to develop both classical and African swine fever vaccines. The project involved two main components: developing diagnostic tests for classical swine fever vaccines and creating attenuated African swine fever virus strains with “improved safety profiles.”

Particularly notable was the African swine fever component, which aimed to develop live attenuated vaccine strains through “genetic manipulation of virus genome and homologous recombination methodology.” The USDA’s Plum Island facility was to provide expertise in developing these attenuated strains and conduct “pilot experiments towards the evaluation of attenuation and immunogenicity,” while IRTA-CReSA would contribute expertise in developing recombinant viruses and help design “novel attenuated strains” based on existing vaccine templates.

The agreement explicitly stated that both institutions would “enter into distinct cooperative agreements to further joint research efforts and when funding opportunities dictate,” indicating an ongoing framework for collaboration on these dangerous pathogens. This research involved creating modified versions of African swine fever virus specifically designed to be less virulent while maintaining their ability to stimulate immune responses—work that requires handling live virus and creating new viral variants in laboratory settings.

The Research Context and International Funding

IRTA-CReSA is one of Europe’s most experienced centers for African swine fever research, conducting both basic and applied research on the virus. The facility operates under high biosafety level 3 (BSL3) conditions and has been designated by international health organizations as a reference laboratory for swine disease research. The laboratory was established as a public research center attached to the Catalan regional government’s Department of Agriculture.

The core mission, activities, facilities and research of IRTA-CReSA include:

Animal health research: IRTA-CReSA studies a wide range of infectious diseases that affect livestock and other animals, including viruses (like swine fevers and avian influenza), bacteria, prions, tuberculosis, and vector-borne diseases. Its work covers disease pathogenesis, epidemiology, diagnostics, and prevention.

One Health approach: Research at IRTA-CReSA often follows the One Health concept, recognizing the interconnectedness of animal, human, and environmental health.

Tools and innovation: The centre develops and evaluates vaccines, diagnostic tools, and computational and laboratory methods to detect and control animal diseases — including collaborations with public administrations and the private sector.

High-containment laboratories: IRTA-CReSA has BSL-3 (biosafety level 3) laboratories and a large biocontainment facility capable of working with high-risk pathogens under strict safety protocols.

Animal experimentation: The centre can safely house and conduct controlled studies with livestock (e.g., pigs, poultry, ruminants), wild animals, and laboratory species under high biosafety conditions.

Bioimaging and technological platforms: It hosts advanced imaging tools and other research infrastructure that support detailed studies of disease processes and therapeutic effects.

IRTA-CReSA has been designated by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH/OIE) as a collaborating centre for research and control of emerging swine diseases in Europe and as an OIE reference laboratory for classical swine fever — reflecting its recognized expertise.

While primarily funded by European and Spanish sources, IRTA-CReSA has also received project-specific funding from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) for swine fever research. Documented USDA funding includes support for classical swine fever vaccine studies in pregnant sows, with published research citing “USDA-IRTA Agreement No. NACA 58-8064-0-013F” as a funding source. The USDA’s Agricultural Research Service has described formal cooperative agreements between its Plum Island Animal Disease Center and IRTA for joint research when funding opportunities exist, establishing an official mechanism for collaborative work on swine diseases.

This international arrangement highlights the global nature of animal disease research and the interconnected network of laboratories working on these pathogens. under “One Health” programmatic justification. The extensive USDA-IRTA cooperative agreement demonstrates that this collaboration involved not just funding but also active joint research to create modified versions of both classical and African swine fever viruses.

There is documented U.S. government funding for swine fever (classical swine fever) work conducted at IRTA-CReSA, and it’s shown explicitly in the funding statements of published pig studies.

A pregnant sow (pig) vaccination/challenge study run by IRTA-CReSA’s WOAH Reference Lab for Classical Swine Fever (“FlagT4G vaccine… in pregnant sows”) lists “USDA-IRTA Agreement No. NACA 58-8064-0-013F” as funding.

The same funding attribution appears in IRTA’s institutional record for that swine fever work, again citing USDA-IRTA Agreement No. NACA 58-8064-0-013F.

Separately, USDA-ARS describes an arrangement where ARS/Plum Island Animal Disease Center (PIADC) and IRTA “enter into distinct cooperative agreements” to pursue joint research when funding opportunities exist—i.e., a formal mechanism used for collaborative work in this space.

So, while the USDA is not providing ongoing “operating” funding of the whole facility, project-specific USDA funding and cooperative agreements are supporting swine fever research in pigs at IRTA-CReSA.

The Ongoing Investigation and Broader Implications

The investigation into the outbreak’s origins continues, with authorities examining whether the virus escaped from laboratory containment or arrived through other means. The fact that the local court declared the investigation proceedings “secret” suggests the seriousness with which Spanish authorities are treating the possibility of a laboratory accident.

While Catalan leader Salvador Illa has stated that no information is “conclusive,” including theories of a laboratory leak, the genetic evidence pointing to a reference strain used in research facilities has kept the laboratory hypothesis prominent in the investigation.

The case has broader implications for laboratory oversight and biosafety protocols. If confirmed as a laboratory accident, it could prompt enhanced oversight of high-containment research facilities and pathogen management protocols across the European Union and beyond. The revelation of extensive international funding arrangements, including a five-year USDA cooperative agreement specifically focused on African swine fever virus manipulation, also raises questions about oversight responsibilities when multiple governments support research at the same facility.

Looking Forward: Science, Safety, and Global Food Security

The Spanish outbreak represents more than just an agricultural crisis—it’s a case study in the complex relationship between scientific research and public safety. Whether the virus escaped from a laboratory or arrived through some other route, the incident highlights the delicate balance between conducting necessary research on dangerous pathogens and ensuring absolute containment.

The police raid and ongoing investigation into potential laboratory origins raise important questions about oversight of high-containment facilities and the protocols needed to prevent accidental releases. The incident demonstrates how quickly serious investigations can emerge when outbreaks occur near scientific facilities, particularly when genetic evidence points toward laboratory strains.

The international funding dimension adds another layer of complexity, as it shows how research on dangerous pathogens often involves collaboration between multiple countries and institutions. The extensive USDA-IRTA cooperative agreement, which specifically involved creating modified African swine fever virus strains, raises questions about who bears responsibility for oversight when funding and expertise come from multiple sources and how to ensure consistent safety standards across international collaborative projects.

For now, Spanish authorities are working around the clock to prevent the virus from spreading to commercial pig farms. The success of these efforts will determine whether this remains a contained incident involving wild animals or becomes a full-scale agricultural disaster affecting one of Europe’s most important food industries.

The outbreak also serves as a stark reminder that in our interconnected world, a biological incident in a small area outside Barcelona can quickly affect global food markets, international trade relationships, and the livelihoods of farmers and workers thousands of miles away. As investigations continue into both the virus’s spread and its possible laboratory origins, the world watches to see whether Spain can contain this ancient pathogen that may have found a modern route back into the wild.

The incident underscores the ongoing challenge of balancing the benefits of pathogen research—including vaccine development and disease preparedness—with the need to minimize risks to both animal and human populations. As global food systems become increasingly interconnected and scientific capabilities continue to advance, such questions about research safety and oversight will likely become even more critical for protecting both public health and economic stability.

The Spanish case may well become a landmark example of how laboratory safety investigations should be conducted, providing lessons for the scientific community, policymakers, and the public about the importance of transparency, proper oversight, and robust containment protocols in high-risk biological research. It also highlights the need for clear accountability frameworks when international funding supports research on dangerous pathogens, ensuring that safety responsibilities are clearly defined regardless of the funding source or the complexity of international collaborative arrangements.

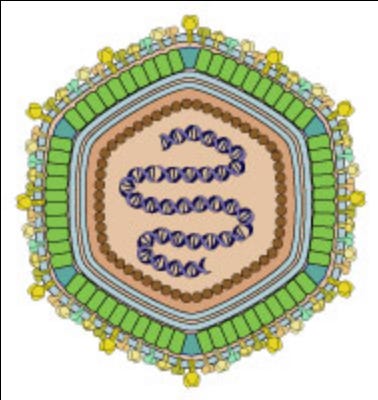

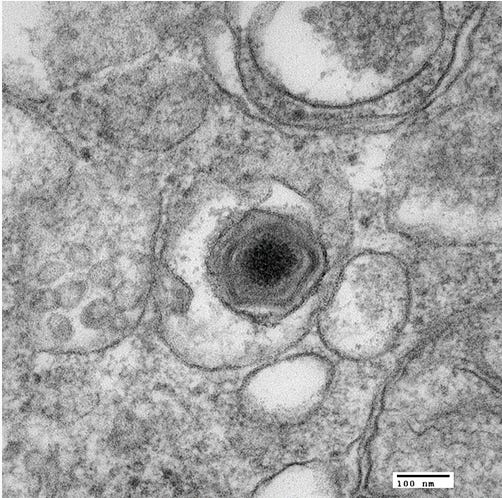

Understanding African Swine Fever: The Virus

African swine fever virus is a biological nightmare for the pork industry. This large DNA virus belongs to the Asfarviridae family and has an enormous genome—170 to 193 kilobase pairs encoding more than 150 proteins. This complexity is part of what makes the virus so dangerous and so difficult to combat.

The virus is remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in processed pork products and persisting in the environment under various temperature and pH conditions, especially when organic matter is present. It can lurk in contaminated areas long after infected animals are gone, making cleanup and prevention extraordinarily challenging.

Importantly for human health, African swine fever poses no danger to people—you can’t catch it, and it doesn’t affect the safety of pork products for consumption. However, this single characteristic is about the only reassuring aspect of this pathogen.

The Disease: A Death Sentence for Pigs

For pigs, African swine fever is often fatal. The virus can kill up to 100% of infected domestic pigs and European wild boars, spreading rapidly through populations and causing massive internal bleeding and devastating inflammation. The disease can manifest in different forms, ranging from chronic infections to hyperacute cases that kill quickly.

Interestingly, the virus shows a stark difference in how it affects different pig species. While it devastates domestic pigs and European wild boars, African warthogs and other native African pig species can carry the virus without showing serious symptoms, acting as natural reservoirs that help maintain the virus in wild populations.

The virus’s ability to evade the host immune system, combined with its complex structure, has prevented scientists from developing an effective vaccine. This leaves containment measures—quarantine, culling infected animals, and disposal—as the only tools available to fight outbreaks.

Conclusion: Lessons from a Crisis

The Spanish African swine fever outbreak of 2025 represents far more than an agricultural emergency—it is becoming a defining case study for how societies must navigate the complex intersection of scientific research, public safety, and global economic interdependence in the 21st century.

Whether the virus escaped from the IRTA-CReSA laboratory or arrived through natural transmission routes, the incident has exposed critical vulnerabilities in our approach to high-risk pathogen research. The genetic evidence pointing to a laboratory reference strain, the proximity of infected animals to an active research facility, and the extensive international collaborations involving virus manipulation have raised fundamental questions that extend far beyond Spain’s borders.

The economic consequences alone—billions in potential losses, disrupted trade relationships, and threatened livelihoods—demonstrate how quickly biological incidents can cascade through interconnected global systems. Spain’s experience shows that in our integrated world economy, a handful of infected wild boars in a Barcelona suburb can instantly affect farmers in Iowa, consumers in Shanghai, and policymakers in Brussels.

Perhaps most significantly, the case has highlighted the challenges of maintaining public trust in scientific institutions while conducting necessary research on dangerous pathogens. The revelation of extensive U.S.-Spanish collaborative research on the African swine fever virus, including work to develop modified viral strains, has intensified debates about transparency, oversight, and accountability in international biological research.

The ongoing criminal investigation, with its court-sealed proceedings and dramatic police raids, reflects the seriousness with which authorities are treating potential laboratory safety failures. Yet it also illustrates the difficulties of conducting such investigations while maintaining the confidentiality that scientific institutions argue is necessary for their work.

Moving forward, the Spanish outbreak offers several critical lessons for policymakers, scientists, and the public:

Enhanced Oversight is Essential: The incident demonstrates that current oversight mechanisms for high-containment research may be insufficient, particularly when international collaborations involve multiple funding sources and regulatory frameworks. Clear lines of responsibility and standardized safety protocols are needed regardless of funding origin.

Transparency Builds Trust: The initial lack of disclosure about the laboratory’s research activities and international collaborations contributed to public suspicion. Greater transparency about high-risk research, while protecting legitimate security concerns, is crucial for maintaining public support for necessary scientific work.

Rapid Response Capabilities Matter: Spain’s swift military deployment and comprehensive containment measures likely prevented a much larger catastrophe. Investment in rapid response capabilities for biological emergencies is essential infrastructure for food security.

Global Cooperation Requires Clear Frameworks: International research collaborations on dangerous pathogens need robust governance structures that clearly define safety responsibilities, oversight mechanisms, and accountability measures across national boundaries.

As investigations continue and Spain works to contain the outbreak, the world watches what may become a landmark case in laboratory safety and scientific governance. The eventual findings—whether they confirm or rule out a laboratory origin—will likely influence policies governing biological research for decades to come.

The Spanish crisis reminds us that the benefits of scientific research on dangerous pathogens, while substantial, come with equally substantial risks that require constant vigilance, robust oversight, and unwavering commitment to safety. In an era where a single laboratory accident can trigger global economic disruption and undermine public trust in science, the stakes for getting this balance right have never been higher.

The ancient pathogen of African swine fever, whether it escaped through modern laboratory walls or found its way back to Europe through more traditional routes, has delivered a modern lesson about the responsibilities that come with our growing scientific capabilities. How well we learn from Spain’s experience may determine whether such incidents become opportunities to improve safety or harbingers of larger crises to come.

This story and issue have not been covered in US corporate media, and this essay may be the most comprehensive analysis yet published.

I don’t get it…. Why do we do gain of function at all? We have a nasty virus so let us spend tax payer resources to see if we can make it really, really, really nasty.